ACT UP encore

New exhibit tracks social movement

The mysterious image was hauntingly simple.

And subversive. A pink triangle, the symbol used by Nazis to identify homosexuals during the Holocaust, was flipped over, pasted against a black background, and emblazoned with two words in white: “Silence = Death.”

The iconic work was plastered on New York City’s streetlamps, painted on its sidewalks, and sprayed on its walls. It was a clarion call during the early years of the AIDS epidemic in the 1980s for people to speak out, fight to be heard, and help the thousands battling a deadly new disease.

Created in 1987 by six gay activists, the Silence = Death Project soon came to symbolize a potent rising protest movement: The AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power (ACT UP). Through targeted campaigns and demonstrations, the activist organization was determined to spread warnings about HIV/AIDS, to make the government take notice, and to fund research and support for a cure.

But to the dismay of Helen Molesworth, Harvard Art Museum’s Maisie K. and James R. Houghton Curator of Contemporary Art, many of today’s generation have forgotten the imagery, the movement, and its importance.

“It is so disturbing that there seems to be this real sense of cultural amnesia around this pivotal time,” said Molesworth, who lived in New York during the height of the movement.

She aims to change that with a new exhibition at the Carpenter Center for the Visual Arts titled “ACT UP New York: Activism, Art, and the AIDS Crisis, 1987–1993,” opening today (Oct. 15). The show examines the history of the movement through a series of powerful graphics created by various artist collectives that were part of the influential group.

Molesworth co-curated the show with Claire Grace, Agnes Mongan Curatorial Intern in the Art Museum’s Department of Modern and Contemporary Art and a graduate student in Harvard University’s History of Art and Architecture program.

ACT UP Gallery Photos by Stephanie Mitchell, Harvard Staff Photographer

Ready for viewing

Edward Lloyd has readied the gallery space for the opening ceremony.

Final touches

Carpenter Center exhibition manager Edward Lloyd sets up the exhibit in the Sert Gallery. The exhibition marks the more than 20 years since the formation of ACT UP.

Pop art

ACT UP’s successful campaign to achieve concrete changes in legal policy and medical practice prompted changes in clinical trials for antiretroviral drugs and prodded pharmaceutical companies to reduce the cost of these drugs, such as AZT.

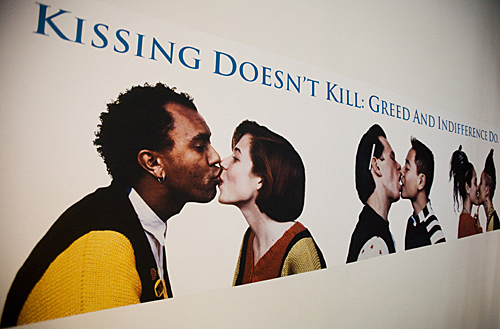

Kiss and tell

A full-scale reproduction of Gran Fury’s famous “Kissing Doesn’t Kill” bus panel from 1989.

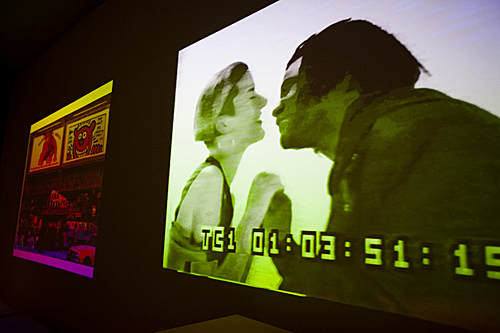

Outtakes

Projectors in the Sert Gallery display footage of past ACT UP demonstrations, including Gran Fury’s “Kissing Doesn’t Kill” photo shoot.

“AIDSGATE”

The Sert Gallery’s “ACT UP New York: Activism, Art, and the AIDS Crisis, 1987-1993” examines the history of the movement through a series of powerful graphics. Among those is a poster of President Ronald Reagan with the word “AIDSGATE.”

On the center’s first floor, a 4-by-6-and-one-half-foot neon version of the Silence = Death image greets visitors in the main gallery. The work is accompanied by the premiere of the ACT UP Oral History Project: more than 100 separate interviews with surviving members of the organization that will run continuously on 14 different monitors.

Organizers understood, said Molesworth, that the fight against AIDS had to be taken to the streets through disruptive demonstrations and traffic-stopping protests that could end in arrests. But they also understood the need to capture the attention of another important sphere of influence: “That was the media, visual culture, billboards, television. … It was a very canny understanding that in order to get this very complicated, multilayered message across to a lot of people, they needed to operate in that realm as well.”

Populated by many artists, filmmakers, graphic designers, and artists, ACT UP was characterized by its media-savvy campaigns and its sharp, often disturbing, in-your-face visuals. In the Sert Gallery on the second floor, more than 70 items created during the movement — posters, stickers, buttons, T-shirts — adorn the walls.

The exhibit includes posters critical of the politicians whom ACT UP deemed ineffective and slow to acknowledge the crisis. On one wall, a bright green image of the face of President Ronald Reagan stares out at the viewer, covered by the word “AIDSGATE.” On another wall, a giant horizontal image — identical to those spread across New York City buses in the ’80s and aimed at galvanizing the public — depicts a series of couples embracing, with the words “Kissing Doesn’t Kill, Greed and Indifference Do” written above them.

One of the exhibit’s most moving elements is a timeline along the wall in the Sert Gallery charting the history of the epidemic and ACT UP’s response. It details the U.S. government’s slow reaction, the homophobia and discrimination associated with the crisis, the growing number of deaths, and the work of ACT UP and its increasingly bold and effective efforts to bring the disease to national attention. The organization’s activism is traced alongside the shocking number of deaths annually, and the dramatic decline in mortality rates once an early AIDS drug regimen was finally made widely available in the mid-’90s.

The art installations are part of a series of programs developed around the ACT UP/HIV/AIDS themes in collaboration with the exhibition.

Realizing they had a wealth of knowledge about the epidemic at their doorstep, the show’s organizers reached out to departments around the University, crafting a broad approach to the topic. The result is a month of lectures, conferences, symposiums, film screenings, and poetry readings with Harvard scholars involved in various aspects of HIV/AIDS scholarship and research.

“We realized that Harvard is a university filled with people working on issues of HIV/AIDS,” said Molesworth, “and one of the things we wanted to do was highlight the extraordinary interdisciplinary work going on across fields in our midst.”

Molesworth said she hopes the exhibit and its companion events will help inspire a younger generation to explore a period in recent history when a social movement had a profound impact and inspired critical change.

“I would love for young people to feel that sense of possibility, that if they wanted to they could stop the war or insist upon a public option in the health care plan, whatever it is that they want … that they can effect dramatic social change.”