“With this exhibition, we really wanted to explore the important role artists played in scientific inquiry of the 16th century,” said Susan Dackerman (right), Carl A. Weyerhaeuser Curator of Prints, who curated the show. Marisa Mandabach (left), a Ph.D. candidate in Harvard’s Department of History of Art and Architecture, assisted in the research.

Justin Ide/Harvard Staff Photographer

When art wed science

Exhibit tracks the melding of two major fields in the 16th century

Albrecht Dürer (1471-1528), considered the greatest artist of the Northern Renaissance, is admired as much for his versatility and range as for his profound mastery of his materials. Portrait painter, draftsman, watercolorist, and, most famously, printmaker, he is perhaps best known for his treatment of biblical and allegorical themes.

But the brilliant, tirelessly inquisitive German artist also altered the world’s vision of the heavens.

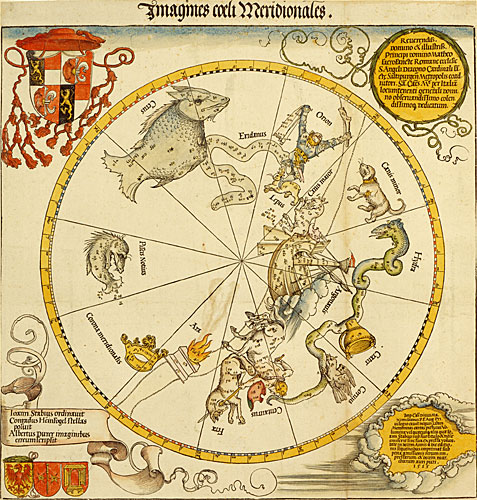

On the fourth floor of Harvard Art Museums/Arthur M. Sackler Museum hang Dürer’s intricate 1515 woodcut prints depicting the constellations of the northern and southern hemispheres with a combination of scientific scrutiny and artistic flair. Made in collaboration with 16th-century mathematician and astronomer Conrad Heinfogel and cartographer Johannes Stabius, and drawing on his own interest in and knowledge of astronomy, the artist carefully created his celestial charts. Never before had the heavens’ constellations been so vividly, accurately, and widely reproduced. The scholarly work changed the history of astronomy.

Dürer’s images represent the type of vibrant exchange that is at the heart of a new exhibition titled “Prints and the Pursuit of Knowledge in Early Modern Europe.” The show, with its collection of prints, books, maps, and instruments like sundials, globes, and astrolabes (a tool used for determining the position of the sun, the moon, and the stars), explores how knowledge was shaped by important collaborations between artists and scholars of the time, using the medium of print.

The exhibit, organized by the Harvard Art Museums/Arthur M. Sackler Museum with objects from repositories across Europe and North America, continues through Dec. 10.

“With this exhibition, we really wanted to explore the important role artists played in scientific inquiry of the 16th century,” said Susan Dackerman, Carl A. Weyerhaeuser Curator of Prints, who curated the show. “One of the things artists did at that time was help theorists visualize kinds of knowledge, and by helping them visualize it, they actually helped them in many cases conceptualize it as well.”

‘Prints and the Pursuit of Knowledge’

Instrument of prediction

This astrolabe, an instrument used to predict the positions of the sun, moon, stars, and planets, was made by Georg Hartmann. Photo courtesy of Adler Planetarium & Astronomy Museum, Chicago

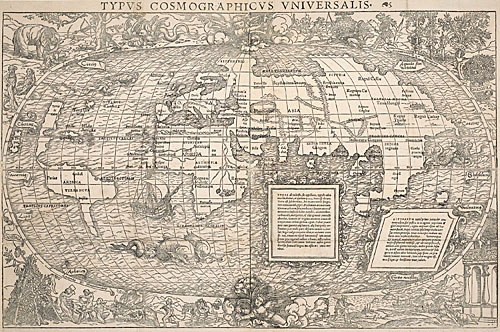

Cosmographic map

With its flattened and elongated spherical form encompassing all the known continents in both hemispheres, this universal cosmographic map by Hans Holbein and Sebastian Munster was an innovative depiction of the Earth for its time. Photo © The Trustees of the British Museum

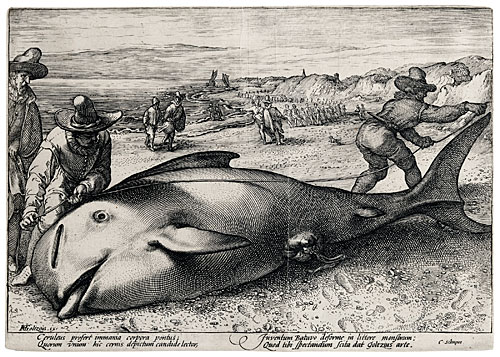

‘Pilot Whale Beached at Zandvoort’

A 1594 etching and engraving by an unknown artist. Department of Digital Imaging and Visual Resources/Harvard Art Museums

Man of many trades

This etching by Jost Amman depicts Wenzel Jamnitzer, a goldsmith, mathematician, and instrument maker. Department of Digital Imaging and Visual Resources/Harvard Art Museums

Around the world

Albrecht Dürer’s celestial charts are the first known printed maps of the northern and southern celestial hemispheres. Photo courtesy of Staatliche Graphische Sammlung München

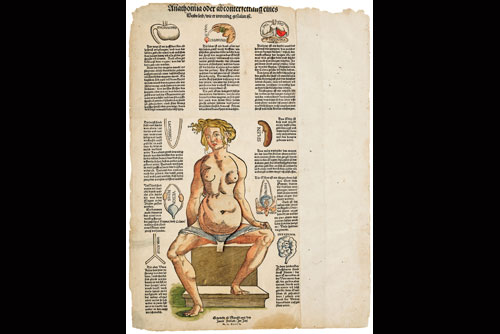

Inside out

Heinrich Vogtherr’s anatomical flap prints of a female (shown here) and a male are another compelling example of how the material qualities of paper influenced the use of prints. Photo courtesy of Boston Medical Library in the Francis A. Countway Library of Medicine

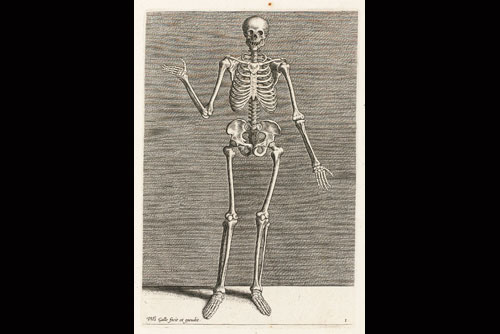

Skeleton by design

An engraving of a skeleton by Philip Galle offered an inside look. Photo courtesy of Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

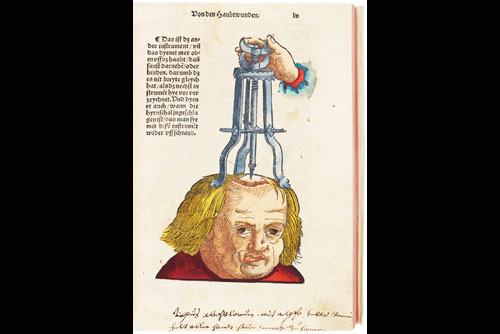

From the top

This “field manual for treatment of wounds” depicts instruments for use in cranial surgery. Courtesy of Philadelphia Museum of Art

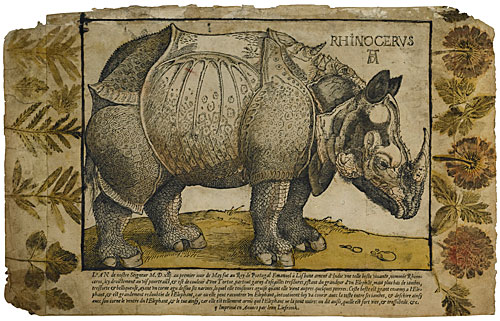

Coloring between the lines

Albrecht Dürer’s “Rhinoceros,” 1515 (1620 edition). The addition of color to Dürer’s “Rhinoceros” masked a horizontal split in the lower left of the block. More important, it attributed a specific color to a creature about which very little was actually known. Photo © Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

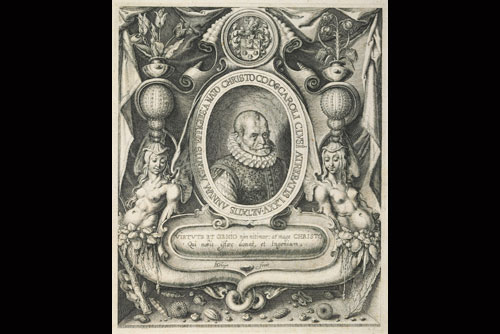

Plant master

This portrait by Jacques de Gheyn II was a frontispiece for Clusius’ groundbreaking “history of rare plants,” with 1,120 woodcut illustrations showing plants in various stages of their life cycles. Department of Digital Imaging and Visual Resources/Harvard Art Museums

Wide-ranging in its scope, the exhibition covers areas like astronomy, cosmography, cartography, and natural history. It delves into the origins of botany and zoology, the history of medicine, and the development of the study of anatomy.

The myriad works in the exhibition reveal how methods of inquiry in the 1500s increasingly relied on direct observation as a way to gather information about the world. Scholars and artists often joined forces to capture accurate images using botanical, human, and animal specimens as their models. Together, and on their own, they created prints of intricate maps, detailed catalogs of plants and animals, complex representations of the human body, and much more.

One example is a print by Cornelis Anthonisz. The Dutch artist likely worked closely with a physician familiar with human dissections, said Dackerman, to create the intricate drawings of the arterial system found in a vivid black-and-white print on display in the fourth-floor galleries.

“The way that the artist cuts the woodblock is as if the arteries are roadways or pathways,” said Dackerman, calling the work a “map of the human body.”

As always, putting your hands on the art remains verboten, but Dackerman and her team wanted visitors to be able to engage with the works, and devised a clever way for visitors to interact with the show. In the 16th century, many of the prints would have been cut up and assembled into scientific instruments or devices for the study of the stars, medicine, or the human anatomy, Dackerman said. Throughout the show are carefully crafted replicas of those instruments. Visitors can handle a globe, a sundial, and an elaborate chart of the human body based on Heinrich Vogtherr’s anatomical prints, with paper flaps that, when lifted, reveal the internal organs of the male and female form.

“We have to think of these kinds of objects as comparable to this kind of invention,” said Dackerman, comparing Vogtherr’s original work, carefully preserved in a large glass case, to her iPhone.

“Putting an object like [Vogtherr’s] in a case renders it static in a way it never would have been in the 16th century,” she said, adding that the facsimiles allow visitors to “have the same kind of visual and tactile engagement with the object that was originally intended.”

Modern technology also plays a part in the exhibition. Located in the gallery are two computers that allow visitors to explore the works through additional text and videos, through the click of a mouse. An iPhone application with Vogtherr’s images is available for download.

The show also reveals how emerging knowledge was being widely disseminated, and updated.

While previous scholarship relied heavily on the study of ancient texts, significant improvements in printmaking techniques meant that prints could be reproduced hundreds and even thousands of times.

They could also be updated.

Often, scholars and artists reworked woodblock carvings or the copper plates used in etchings, adding new discoveries, insights, and information as it became available into outdated prints.

“In a way it was like Wikipedia, where the work would reflect an ongoing discourse as opposed to a canon of knowledge that was set in stone. It’s very modern,” said Marisa Mandabach, a Ph.D. candidate in Harvard’s Department of History of Art and Architecture, and one of the many graduate students who conducted research for the show.

When Dackerman arrived at Harvard in 2005, she began discussing the concept for the show with Katharine Park, the Samuel Zemurray Jr. and Doris Zemurray Stone Radcliffe Professor of the History of Science.

Together, they developed an interdisciplinary seminar at Harvard’s Mahindra Humanities Center. During the monthly meetings, students and faculty explored materials from the University’s vast collections and investigated various areas of research. The show and corresponding catalog blossomed from those discussions.

“The exhibition really evolved organically,” said Dackerman, “as a result of this conversation between professors and graduate students in wide-ranging fields.”

The exhibit is reminiscent of last year’s show in Harvard’s Science Center, titled “Paper Worlds: Printing Knowledge in Early Modern Europe.” The product of a similar graduate student seminar also taught by Dackerman and Park, 10 graduate students and a Harvard paper conservator created the 2010 show.

An opening panel discussion and reception will be held Sept. 6 from 5 to 8 p.m. A symposium will be held Dec. 2 from 5 to 8 p.m. (evening program), and Dec. 3 from 8:30 a.m. to 6:30 p.m. (daytime program). For more special programming related to the exhibition, such as tours, talks, concerts, and Family Days, see the “Prints and the Pursuit of Knowledge” section of the museum calendar.