Pforzheimer House residents Suzanna Bobadilla (right) and Matt Chuchul are the primary student organizers of a one-night exhibit on Harvard’s “great co-educational experiment” called “The Residential Revolution: The History of Gender and Pfoho Student Life,” an exhibit and celebration of House history held in Holmes Hall on Feb. 15.

Rose Lincoln/Harvard Staff Photographer

Remembering the co-ed experiment

Pfoho residents uncover, celebrate history 40 years after House integration

Suzanna Bobadilla had always been a little curious about the trappings of her Pforzheimer House residence. Her sophomore year in Comstock Hall, she noticed small latches on each door frame that would prop a door open by a few inches. And then there were the floor-length, three-pane mirrors, like those at a department store, located at the end of the hall on every floor.

As it turned out, the architectural oddities had a common thread: They were included with women in mind. In the early years of the House’s existence, its residents — female Radcliffe students — were asked to keep their doors ajar when entertaining gentlemen guests, and could use the mirrors to check themselves on their way out the door.

“There’s this weird history of Pfoho that’s very gendered, that hadn’t been formally documented or written down,” Bobadilla said. So she and her classmate, Matt Chuchul, co-chair of Pfoho’s House committee, decided to do just that.

Their resulting search through University archives and the hidden corners of Pfoho turned up important pieces of House history — and shed light on the controversial turning point 40 years ago when Pforzheimer and the all-male Winthrop House undertook Harvard’s first “great co-educational experiment.” By swapping 50 men and 50 women for the 1969-70 school year, the Houses marked the beginning of a revolutionary (for Harvard) change in campus life.

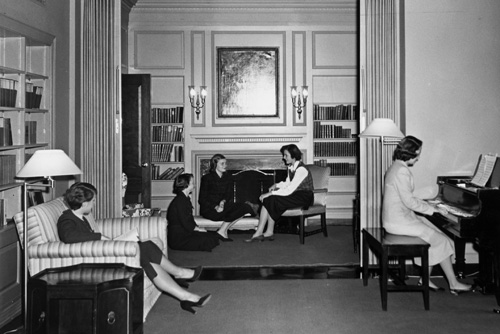

Bobadilla and Chuchul, both junior history and literature concentrators, spent three weeks in the Schlesinger Archives reading over aging files and looking at old photographs. With the help of the Harvard College Women’s Center, where Bobadilla is an intern, and officials at Pforzheimer House, they organized “The Residential Revolution: The History of Gender and Pfoho Student Life,” an exhibit and celebration of House history held in Holmes Hall on Feb. 15.

The evening event included artifacts, photographs, and personal testimonies from several Pfoho alumni, who mingled with current students and staff. Perhaps the highlight of the event was the collection of documents on display, which outlined House procedures from the all-women era.

“Men are not to be in the halls upstairs unescorted by a Moors girl,” one warned sternly, referring to one of the House dormitories. “They should neither linger in the halls, nor on the phone, nor talking, nor in the smokers.”

Much of the North House (as Pfoho was then called) arcana came not from Harvard archives, but from a stroke of good luck. Chuchul stumbled across an old filing cabinet in one of Pfoho’s musty basement boiler rooms; when he and Bobadilla opened it, they found decades’ worth of House records. They plan to donate the trove to the Schlesinger Library and hang some photographs from the era in Pfoho common rooms.

“It’s really a forgotten history,” Chuchul said. “We wanted to get people talking with one another and thinking about it again.”

That history still remains alive and well among the women of North House, some of whom attended the celebration. Meryl Stowbridge ’71, who lived in Moors Hall before integration, recalled being “on bells,” a mandatory chore that required taking phone calls at the front desk and taking messages for any girls who were out.

While the customs from her North House days seem quaint now, the sense of community it engendered among Cliffies was real, she said. “Any time a minority gets its rights and integrates, there’s always a little bit of regret at losing that solidarity.”

The move toward co-ed living seemed long overdue by the time Winthrop and North Houses (along with Adams and Lowell and Radcliffe’s East and South Houses) agreed to swap residents, alumnae said. But the social particulars still had to be negotiated.

“We were something like 50 women to 300 men,” said Helen Snively ’71, who moved from North to Winthrop during her junior year. “We were kind of curiosities. … Winthrop was all these jocks, and I didn’t know what to say about baseball.” But by the end of that year, she said, “I’d finally found a place to belong — my social home.”

Harvard’s 375th anniversary has proven to be an opportune time to reflect on the history of the female experience on campus. The Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study is putting together a retrospective lecture on women’s history at Harvard for April. The Office of Faculty Development & Diversity, in its 2011 annual report, produced the first comprehensive timeline of female faculty appointments at Harvard, identifying the first five tenured women at each School.

“It’s important to highlight people who are not just white males who have done amazing things here at Harvard,” said Gina Helfrich, director of the Women’s Center, who helped to organize the Pfoho exhibit. “Looking at how much the diversity of the undergraduate population has changed from the early years, and even from the mid-20th century, is a great way to highlight the progress we’ve made.”

Of course, the great co-educational experiment — and the resulting increase in Harvard’s female student ranks — affected Harvard men, too.

“It allowed men and women to hang out and become friends, not to just be dating objects for one another,” Bobadilla said. Without Pfoho student life to bring them together over late-night study sessions or dining hall breakfasts, Bobadilla and Chuchul might not have become such close friends. And Pfoho might never have recovered its lost bit of House history.

“That’s true,” Chuchul said with a laugh.