Leslie Morris, Houghton’s curator of modern books and manuscripts, assembled “John Updike: A Glimpse from the Archive,” an exhibit on view at the Houghton Library through June 30. Three glass cases are clever summaries of where Updike came from intellectually, how he worked, and how eccentric literary archives can be.

Photos by Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

Updike’s roots and evolution

Library exhibit offers tantalizing insights into author

John Updike (1932-2009) wrote more than 50 books, winning the Pulitzer Prize twice and the National Book Award four times. Which is to say: He knew what he was doing, and he did it with remarkable energy.

But how did Updike, the boy from rural Pennsylvania, become Updike the international literary icon? Part of the answer, no doubt, is captive inside the John Updike Archive at Harvard’s Houghton Library, in the drafts, drawings, letters, reviews, photos, books, and miscellania acquired from his estate in 2009. (The writer himself, in prior decades, dropped off much of the archive himself, box by neatly organized box.)

In particular, “the Harvard material helps you understand where he came from, how he developed in the ways that he did,” said Leslie Morris, Houghton’s curator of modern books and manuscripts, who assembled the display.

The 1,635 books in the Updike archive are already available to scholars. Manuscripts will be ready as early as August, and correspondence will be open to researchers by the end of the year. The novel on which he was working at the time of his death, which involved St. Paul and early Christianity, will not be available until 2029.

“What he finished was not very long,” said Morris, who knew Updike and who helped to retrieve material from his home office in 2009. “It was pretty rough.”

For those who can’t wait, a short-lived exhibit at the Houghton’s Amy Lowell Room, open to the public through June 30, offers a glimpse of the Updike treasures. (“John Updike: A Glimpse from the Archive” was assembled from the archive itself, which is funded by the Amy Lowell Trust, the Charles Warren American History Fund, and private donations.)

Three glass cases are clever summaries of where Updike came from intellectually (Harvard, where he was part of the Class of 1954); how he worked (meticulously and thoroughly, as seen from drafts of his work and examples of his research); and how eccentric literary archives can be. The third case, for instance, includes his favorite kind of ballpoint pen, which he got as free samples from his Boston ophthalmologist. “He was very frugal,” observed Morris.

You can’t see the last novel Updike was writing, but you can see a 2009 view of the little desk on which he was writing it. There is a small lineup of hardbacks, including a tome on first-century Romano-Jewish historian Titus Flavius Josephus. But there is also, inexplicably, a rectangle of corrugated board and a bottle of Elmer’s Glue. (Scholars, start your musing.)

The same case includes two blunted red pencils (Updike was a fervent self-editor) and a Paper Mate Sharpwriter #2. “If you had the pen that Keats wrote with or that Dickinson wrote with,” said Morris, “you’d be interested.”

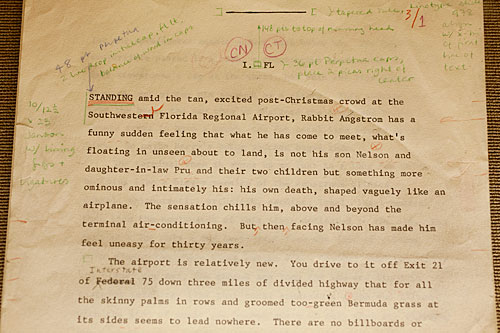

In the second glass case, there are draft pages of “Rabbit At Rest” (1990), the final novel of four in a series begun in 1960. Study the opening paragraph, and you can see Updike transform a mundane first try into prose that is crystalline and resonant. The drafts, handwritten and typed, “show how he really did work at things,” said Morris. “You pick up the paperback, and you don’t have any sense really of what went into it. Here, you see him working on his language.”

You can also see how far a great novelist will go to get the details right. In the same case is a lengthy report on a Manhattan Toyota dealership (Rabbit got rich by selling cars), a hospital brochure (Rabbit got ill), and an empty, 99-cent bag of Keystone Corn Chips (Ask the scholars). “How many novelists really do research?” asked Morris. “Not that many.”

There are also artifacts from Updike’s maturing — and eventually star-studded — literary life: letters from John Cheever, Philip Roth, Kurt Vonnegut, and William Keepers Maxwell Jr., the longtime fiction editor at The New Yorker magazine, where Updike got his start at being famous.

The Maxwell letter is undated, but must have been fairly early, when Updike still needed money. “Dear John,” it starts. “Mr. Shawn [The New Yorker editor William Shawn] thought of a way to give you some more money — by deciding that this piece was funnier than originally paid for.”

There is also a pen-and ink letter to Updike from his “Bech” book illustrator, Arnold Roth, who depicts his friend, wild-haired and flurry-fingered, at the typewriter. Roth has himself saying, in the background, what we would all say: “Geez, I wish that I’d said that!”

But it is the first glass case that provides glimpses of Updike becoming Updike, beginning with a sample of his frequent letters home. (His mother collected many of his undergraduate letters, which were signed “Johnny,” in three bound volumes.) “It is rather unfortunate,” Updike wrote his parents in February of his freshman year, “that one who came to Harvard to avoid hazing should have been accepted into the sole campus organization [the Harvard Lampoon] preserving this pagan tradition.” He wondered how this could befall “one who has just discovered Joyce, Swift, and Pope.”

And Shakespeare, of course. The same glass case includes Updike’s copy of “Romeo and Juliet” from his 1951 course with Harvard teaching legend Harry Levin. Updike’s marginalia, in fountain-pen ink, are dense and intense, revealing him to be, early on, the fierce reader who made the fervent writer. “He was a very committed reader,” an exhibit viewer observed. Morris replied, “This is Harvard.”

Visiting the exhibit on June 13 will be enthusiasts attending the Second Biennial John Updike Society Conference in Boston. It’s hard to say what Updike would think of that, said Morris. “He didn’t like the whole idea of author societies. That’s why there wasn’t an Updike Society until he died.”

But what would he think of the Houghton exhibit? “He’d be secretly pleased,” she said. For one thing, there was a display of Updike archival materials at Houghton when Updike was still alive, in 1987, “The Art of Adding and the Art of Taking Away.”

And besides, said Morris, “Harvard meant a lot to him.”