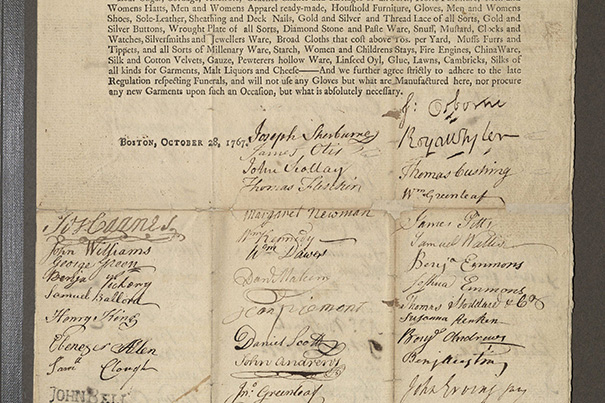

Signatures on the boycott petition included merchants such as Joseph Sherburne and Royall Tyler; soon-famous patriots like midnight rider William Dawes and — in a portrait — Bunker Hill hero Joseph Warren; and dozens of Boston’s unsung future revolutionaries: women.

Photos courtesy of Houghton Library

Revolutionary discovery

Colonists’ 1767 petition uncovered in a Harvard library foreshadows the split with Britain

Harvard archivists have made what they call “a Revolutionary discovery” in the stacks at Houghton Library.

Karen Nipps, head of the Rare Book Cataloging Team, came across eight “subscription sheets,” signed petitions dated “Boston, October 28, 1767.” The documents record one of the early calls for Colonial Americans to boycott British goods. The British had just imposed the Townsend Acts, requiring heavy tariffs on British goods. Six years later, the same tensions sparked the famed Boston Tea Party. Civil actions like these foreshadowed the American Revolution.

In 1767, the signers pledged not to buy goods imported from Britain and its other colonies after Dec. 31. The list of boycotted articles opens a window on 18th-century American imports, including furniture, loaf sugar, nails, anchors, hats, shoe leather, linseed oil, glue, malt liquors, starch, gauze, and the dress gloves worn at funerals.

Historians had known about the boycott, which was called a “nonimportation agreement.” Records exist of a town meeting at Faneuil Hall on Oct. 28, 1767, which preceded the signatures. But until now, scholars had no idea how many colonists had pledged to participate or who they were.

“It’s an exciting discovery,” said John Overholt, Houghton’s curator of early modern books and manuscripts. “It’s going to be the subject of scholarly attention.”

The sheer number of signatures — more than 650 – is attention-getting. In 1767, after all, Boston was a town of only 15,000 people, including 8,000 children. Historians of early America are also eager to pore over the names of the signatories themselves. It will be a first for those who study the connection between consumer boycotts and the Revolution.

Beyond names, the signatures reveal the tensions and crisscrossing loyalties of the time. Next to some of the names are scribbled notes saying that the person signing is pledging to boycott only for a year. Other signatures are scratched out.

The passion to boycott even crossed political lines, said Overholt. “It’s not all firebrand revolutionaries.” Some of the signers ended up Loyalists.

Scholarly attention is already picking up speed. The documents were uncovered on July 10 during a project to catalog older library acquisitions. On July 11, alert to the significance of the signature sheets, Overholt announced them in a Houghton Library blog post. By July 12, the first scholar, Samuel A. Forman, made a visit.

“I have never seen 650 individual signatures on any communal document of this time,” he said, “much less one comprising a link in the chain toward eventual independence.” Forman, an author and scholar of early America, is a visiting scientist at the Harvard School of Public Health. His book “Dr. Joseph Warren: The Boston Tea Party, Bunker Hill, and the Birth of American Liberty” appeared last year.

Primary sources from that era can be fragmentary, he said, and the find at Houghton “provides a record of individual agency and group dynamics that historians and biographers will find compelling.”

Others scholars are in line to see the documents, said Overholt, and they are in luck. The eight sheets — browned and creased but on good rag stock — are now fully digitized.

Beyond the big numbers, the names of those who signed the boycott petitions tell another story. Some went on to become icons of the Revolution. Midnight riders Paul Revere and William Dawes signed. So did James Otis Jr., the Boston lawyer and pamphleteer who wrote the words that came to represent the core of the fight for independence: “Taxation without representation is tyranny.”

Also signing the pledge was Joseph Warren, the subject of Forman’s book. A physician, he was killed at the Battle of Bunker Hill while fighting as a private soldier. The little-known patriot, a 1759 graduate of Harvard College, dispatched Revere and Dawes on their famous ride.

Warren was also the author of the Suffolk Resolves, a 1774 declaration by Suffolk County to boycott all British goods. (Britain’s Massachusetts Government Act had just given royal governors expanded powers.) The Resolves echoed the 1767 boycott, but with sharpened rhetoric. Great Britain, the document began, had “persecuted, scourged, and exiled our fugitive parents from their native shores, [and] now pursues us, their guiltless children, with unrelenting severity.”

Forman called the Resolves “a far more eloquent, forceful, and politically adept effort” than the 1767 boycott. They were adopted by the First Continental Congress and foreshadow the stinging language of the Declaration of Independence.

As a physician, Warren also had a role in the earliest intimations of the revolution to come. In February 1760, he performed an autopsy on Christopher Snider, a 12-year-old boy killed during a protest against a British customs agent. It was the first casualty of the unrest to come, including the Boston Massacre 11 days later.

To the British, the most significant signatures on the petition of 1767 were likely the Bostonians who wielded real power. Among them were prominent landowner Joseph Sherburne, one of the first to sign, and Royall Tyler, a wealthy merchant and politician.

To today’s scholars of early America, however, the list includes a signature of special (if arcane) interest: Harbottle Dorr Jr. His annotated collection of Revolutionary-era American newspapers — a kind of day-by-day record of revolt — resides at the Massachusetts Historical Society.

Identifying Dorr might be a leap for most of us. But try the names of some other signatories, including Rebekah Walker, Elizabeth Clark, and Mary Williams. The free mix of male and female names on the boycott document offers a rare glimpse into the pre-Revolutionary passions that crossed gender lines.

“These women were far from shrinking violets,” said Forman. The newly found documents will reveal “names and associations” that place women at the center of the gathering revolution, he said – “this foundational juncture within volatile late Colonial Massachusetts and Boston.”

Beyond scholarship, the signature sheets themselves were personally resonant, said Forman. “I felt the weight of history.”