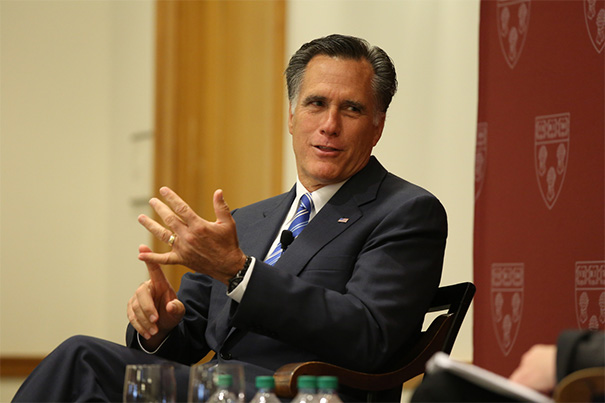

Mitt Romney was asked by Dean Martha Minow if he ever draws on anything he learned at Harvard Law School. “Yes — argument,” Romney replied, to laughter from the more than 350 students in the audience on Friday.

Heratch Photography ©

Closing the information gap

Romney cites increasing polarization in U.S. and the risk it carries

Campaigning for governor of Massachusetts in 2002, Mitt Romney, J.D./M.B.A. ’75, decided he would spend one day every week doing someone else’s job. He cooked hot dogs at Fenway Park, worked at a day care center, took a turn on a paving crew. One day he hung off the back of a garbage truck making its rounds through the city of Boston.

“It was really educational,” Romney said, recalling the experience for a Harvard Law School audience on Friday. “We’d pull up to a corner and there’d be people waiting to cross the street, and I’m not more than two feet from these people. And they don’t see you. You’re invisible. If you’re on a garbage truck, you’re an invisible person.

“I thought, wow — we don’t see each other as we ought to in society.”

The former Massachusetts governor and Republican presidential nominee, visiting Harvard Law School (HLS) for a Q&A session hosted by Dean Martha Minow, encouraged a renewed civility in politics and society, emphasizing the difference one person can make through serving others.

Polarization in the country “is real and becoming worse,” Romney said. “One of the reasons for that is that we don’t get the same information. Thirty, 40 years ago, there were three networks, three news programs, and we all watched an hour of evening news. We also got our news from a certain number of newspapers … we had the same foundation in terms of information.

“Today, conservatives tend to get their news from one series of sources that they tend to agree with, and liberals tend to get their news from another series of sources that they tend to agree with,” he continued. “We rarely have people with the same set of facts. That makes us become more and more polarized, because we look at others and say, ‘How in the world could you possibly think what you do? Knowing what I know, how could you think what you do?’ But they don’t know what you know, and you don’t know what they know, because you haven’t looked at the same facts.

“I’m hopeful that people of capacity will take the time not just to read and to watch what they agree with, but to understand what they disagree with,” he said. “The more polarized we become, the more I look for the kind of person who can step forward and bring people together. There are people who say they will do that but don’t. Our country desperately needs leaders who will stand up and bring us together and find ways to bridge the gaps of understanding between people. We’ve been missing that, and we need it.”

For Republicans to once more be competitive in the Northeast, he said, the party needs to do a better job of communicating why its policies are most effective at helping the poor and the middle class.

“Our opposition party has done a great job of characterizing us as the party of the rich,” Romney said. “The rich will do fine whether Republicans or Democrats are presidents or governors. The rich do fine anywhere in the world. The rich take care of themselves very well. The question is, who is going to do the best job for the middle class and the poor?

“The reason I ran for office — the reason I ran for governor, the reason I ran for president — is because I believed my policies and my leadership would be most likely to help people come out of poverty and most likely to help the middle class see better incomes and better outcomes. I’m convinced that conservative principles create more enterprises and more good jobs, which causes competition to hire people, which causes wages to go up. That’s why I’m a Republican. We have difficulty as a party breaking through and getting that message out.”

Romney was asked by Minow if he ever draws on anything he learned at Harvard Law School.

“Yes — argument,” Romney replied, to laughter from the more than 350 students in the audience in WCC Milstein East.

Romney said law professors like Phillip Areeda and Stephen Breyer “would ask for you to state a case and express your opinion on an item, and inevitably they would ask, ‘Why?’ — and push you to defend your position.

“I went through the joint business-law program,” he recalled. “A little saying we had was [that] you could tell the difference between law students and business students: Business students had bags under the eyes because of all the reading they had to do. Law students had furrowed brows, because of all the thinking they had to do.

“I remember Professor Areeda one day was just zeroing in on me. I gave an answer and he came back and pushed against me and said, ‘Yes, but Mr. Romney, how about this and this and this?’ He kept on going and going for quite a while. … When he was finished with me, he moved on to somebody else. I went back to start writing down some notes of the interchange, and he came back and asked me what did I think about what she had said? I hadn’t paid any attention! He asked, ‘Mr. Romney, why weren’t you paying attention?’ I said I was too busy writing down what I had just said! He chuckled and moved on.

“There’s no question the thinking process, the delving deeper, the pushing deeper in your analysis that is pursued here at the Law School is critical to a career in the private sector or in the public sector,” Romney said.

Romney’s appearance was cosponsored by the HLS Dean’s Office, HLS Republicans, HLS Democrats, and the Harvard Federalist Society.