Harvard Kennedy School and Harvard Business School Professor Max Bazerman speaks about his new behavioral research/book on leadership and noticing. He is pictured outside HKS at Harvard University. Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

Crossing disciplines, finding knowledge

Harvard’s Schools and offshoots are collaborating more often across academic boundaries, prompting innovation leading to discovery

One of the most enduring figures in popular culture is the absent-minded professor, the intellectual so immersed in the cerebral that he often loses track of everyday life. The Greek philosopher Thales once took a nighttime walk, gazing up at the stars, and fell into a well. A servant found Sir Isaac Newton in the kitchen one day, holding an egg and boiling his watch. Margaret Fuller complained to Ralph Waldo Emerson in a letter: “You are intellect. I am life!”

At Harvard, many centers, courses, and collaborations maintain a sharp focus on the intellect, but they increasingly also are working to address everyday issues in life, and they’re crossing academic boundaries to do so more effectively. For instance:

- At the Harvard Kennedy School (HKS), the Behavioral Insights Group (BIG) is reaching across disciplines and Schools to puzzle out how humans make decisions. The findings of these investigations — translated into gentle “nudges” — could have enormous social benefits, including more attentive consumers, voters, and students.

- For Harvard’s Origins of Life Initiative, intellectual rigor targets a fundamental question: At the micro scale, biologists and chemists are trying to understand how inanimate molecules assemble into living cells. At the macro scale, astrobiologists are searching for signals of different life within the atmospheres of exoplanets.

- At Harvard’s Faculty of Arts and Sciences (FAS), humanities students are working with thought-provoking artifacts that illuminate lives from the distant past. This “scholarship of things,” contained in new courses and museum collaborations, is energizing inquiries that traditionally were bound to texts. “There are noble books,” said Fuller in another letter to Emerson, “but one wants the breath of life sometimes.”

- The fundamental learning skills of looking, listening, and reading have been incorporated into a new set of “frameworks” courses in the humanities. If you can exercise these skills effectively through life, the argument goes, you’re less likely to boil your watch.

Here are some prime examples of how Harvard is bringing more pragmatic concerns into the classroom and into new cross-School collaborations:

Schools share insights to solve pragmatic problems

Helping to improve the world is often an elusive goal, but it could get easier if researchers better understood why people act as they do. Toward that end, the field of behavioral science tries to uncover the underpinnings of human motivation and decision-making as part of its mission to study social interaction.

Influential behavioral science research happens across Harvard in important if disparate realms such as economics, psychology, business, law, government, education, and public health. Added together, they make the University one of the world’s leading hubs for that cutting-edge scholarship.

Working to harness the power of collective wisdom, the Behavioral Insights Group (BIG) at Harvard Kennedy School (HKS) has assembled 28 decision-research scholars, behavioral economists, and behavioral scientists from across Harvard to share their work and develop evidence-based approaches to public policy problems that bedevil governments, school districts, and other organizations, including key issues like student underachievement, gender inequality in the workplace, and even tax collection.

“It’s a new collaboration in which the scholars are learning what kinds of problems are important to the people in government, business, and NGOs. And practitioners are learning what kinds of tools they might use from the scholars. And they’re making something together,” said Iris Bohnet, who co-directs BIG with Max Bazerman, the Jesse Isidor Strauss Professor of Business Administration at Harvard Business School (HBS).

“This is an area in which the science connects to policy outcomes pretty quickly, and there’s a lot of interaction right now between policymakers and scholars. And that’s really, really exciting because too often the distance between the ivory tower and people actually trying to solve problems is pretty vast, and there’s a huge translational effort that needs to be done,” said Archon Fung, academic dean and Ford Foundation Professor of Democracy and Citizenship at HKS.

Because decision-making research shows that meaningful improvements don’t always require sweeping initiatives, most policy fixes are modest interventions, or “nudges.”

“A nudge is a little push that builds on insights into how our minds work to help people overcome some of their biases, and make better decisions for themselves and hopefully also for the world,” said Bohnet, a professor of public policy and director of the Women and Public Policy Program at HKS. She studies how behavioral science can improve gender equality.

The nudge concept was first popularized by the 2008 bestseller from Richard Thaler, an economist at the University of Chicago, and Cass Sunstein, now the Robert Walmsley University Professor at Harvard Law School (HLS). Sunstein is a member of BIG, along with, among others, economists David Laibson (FAS), Bridget Terry Long (Harvard Graduate School of Education), Brigitte Madrian (HKS), Sendhil Mullainathan (FAS), Richard Zeckhauser (HKS), political scientist Michael Hiscox (FAS), statistician and legal scholar Jim Greiner (HLS), and HBS behavioral scientists Francesca Gino and Michael I. Norton.

“That’s also what makes it exciting. It’s young, it’s a new perspective, it’s cross- disciplinary, it’s action oriented.” And best of all, most interventions appear to make a difference with relatively low cost, Bohnet said.

For faculty, BIG is a welcome outgrowth of groundbreaking work in the behavioral sciences over the past two decades.

“In the last 15 years, there’s been a real deep and growing interest in nonfinancial … nonregulatory ways to improve societal welfare,” said Todd Rogers, an assistant professor of public policy at HKS and a BIG member. “So all the disciplines that are interested in human welfare have started to look [at]: Are there whole categories of levers that we’ve never considered?”

Rogers’ prior work, using novel behavioral science-tested strategies to motivate voters to the polls, was chronicled in the 2012 book “The Victory Lab.” Now, he focuses on finding practical, scientifically tested efforts to help students and their families support achievement at school.

In Rogers’ Student Social Support R&D Lab, researchers examine how to connect parents better to what’s happening in the classroom, to find ways to get students’ social networks to provide support with online learning, and to correct what Rogers calls the “miscalibrated beliefs” held by families about how their children compare with others.

In one experiment, Rogers partnered with a behavioral insights team in Britain to see whether alerting families that their children had an upcoming test would affect student performance. So researchers sent text messages to families five days before a test, with a friendly reminder. “Turns out, it has this embarrassingly large effect size on improving test scores,” said Rogers. “And parents like it, and kids like it.”

In another test, families of children with high truancy rates were sent comparison mailers showing how often their children were absent from school and how that number compared with others. Because parents often don’t know what constitutes “normal” attendance, said Rogers, they had no frame of reference until receiving the mailer. Once they did, peer pressure was “extremely effective” in increasing attendance without further burdening teachers.

That same dynamic is at work for Opower, a clean energy software company started by two Harvard alumni that uses behavioral science and big data to change how utility companies and consumers manage and use energy. Operating from research conducted by Rogers, the firm sends out mailers to inform households about their energy usage. When people are told they use more energy than their neighbors, they cut back and do so even after the mailers stop coming.

“The Behavioral Insights Group is fantastic for me and the kind of research I do,” said Rogers. “For me, the greatest value is organizing a network around the University of other scholars to provide feedback, generate ideas, and collaborate with on this kind of policy-relevant behavioral science. All of our work becomes easier, more productive, and higher impact by working together and helping each other.”

In addition to fostering University collaboration via regular seminars so faculty can present research to colleagues, BIG co-hosts an annual global conference, supports small workshops in areas like charitable giving or gender discrimination to link scholars with practitioners, and funds student projects. It also offers more than three dozen related courses and a summer workshop for Ph.D. students that are all in demand. A behavioral study group formed by students now has 300 participants.

“It’s a very hot topic for our students because it feels so tangible,” said Bohnet.

This year, Bazerman helped take students to Britain and the Netherlands on immersive field visits to work with government-affiliated clients on public policy projects. Because of its popularity, the course will be offered next year and may include students at Harvard’s T.H. Chan School of Public Health.

“The biggest surprise is that we created this as a research unit. But after we were up and running, professional school students — not just doctoral students — showed up in large numbers and said: What about us?” said Bazerman. “The latent interest in students has been something quite stunning to us.”

Macro to micro: Studying vast cosmos and tiny cells to find life in the universe

People have wondered “Are we alone in the universe?” for generations, but this is the first one that has a chance to answer the question. That prospect is increasingly energizing astrophysicists and biologists, drawing young scholars into the interdisciplinary study of life’s beginnings.

The quest to discern the origins of life is bringing together once-disparate disciplines, including astrophysics and planetary science (concerned with the heavens and the formation of planets), and chemistry and biology (concerned with the prebiotic chemistry and the critical — and still mysterious — transition that created the first living cells).

While some established scientists may need to augment past training to explore novel aspects of the cosmic question, today’s young scientists and students are becoming interdisciplinary natives, said Phillips Professor of Astronomy Dimitar Sasselov.

“It’s like having kids who are culturally bilingual, who learn two languages as toddlers,” Sasselov said. “They have an intuitive sense for the fields — life and physical sciences — rather than learning one of them later on.”

Some students, as they become scholars, are taking the expertise they have learned at Harvard — one of the first centers for origins-of-life research — to other institutions, creating centers where knowledge can flow. Sasselov points to scientists such as Lisa Kaltenegger, who did postdoctoral research at Harvard and now directs Cornell’s Carl Sagan Institute.

“It is key to have a deep understanding in one discipline, like astronomy and planetary science,” Kaltenegger said, “but a broad overview of other involved fields, like biology or chemistry — as well as to ask questions in a way no one has asked before and find connections no one has yet seen — further our understanding of our place in the universe.”

Advances in technology, coupled with the achievements of talented and creative scientists, have opened avenues of inquiry and filled in numerous blanks. Scientists now know for example, that the universe is rich with small, rocky planets like Earth that, if orbiting in their stars’ habitable zones, could harbor life.

Such discoveries have made it important for experts in disparate fields to communicate and link up to understand complex issues. How, for example, can planetary conditions foster or discourage life? And how, once established, can life alter a planet, in the process creating physical signals that might be detected?

“How do we study and explore those exoplanets, accounting for the possibility that life is part of that planet, having transformed that planet?” Sasselov asked. “To what extent is environment determining the chemistry? If that chemistry becomes viable life, to what extent is that life going to transform the environment? That’s a critical question to the big goal for us, which is designing a search for life on other planets.”

Jack Szostak, professor of chemistry and chemical biology in FAS and professor of genetics at Harvard Medical School (HMS) and Harvard-affiliated Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH), is studying the nature-of-life issue from the other end, trying to figure out how inanimate molecules assembled into those first living cells.

“We have no idea how easy or hard that process [of creating life] is and, hence, no idea whether life might exist only here or might be common elsewhere,” Szostak said. “If we had a single independent example” other than Earth, “it would say that it can’t be that hard. So we’re trying to do experiments in the lab that get us a coherent, continuous pathway from chemistry to biology.”

Such fundamental questions exert a gravitational force of their own, Sasselov said. As the founding director of Harvard’s Origins of Life Initiative, which provides a hub for faculty members from across the University to coalesce on this question, one of the easiest parts in justifying the initiative’s founding was assuring student interest.

“I was amazed that we are scientifically able to answer this question,” Sarah Rugheimer said in January, just before defending her doctoral thesis on detecting life’s signals in exoplanet atmospheres. “Are we alone? What’s our place in the universe? Are we special? Are we not?”

Irene Chen, who conducted research in Szostak’s lab before receiving an M.D./Ph.D. in 2007, said the question is still compelling to her today, as an assistant professor of chemistry and biochemistry at the University of California, Santa Barbara.

“It’s a difficult question to answer, but the beauty of it is that it can be tackled from so many different scientific angles,” Chen said. “This field is attractive to students on an intellectual level because of the depth and diversity of questions it raises.”

The scholarship of things: Using objects to bring learning alive

At a current Harvard exhibition, viewers can peer at vials of human teeth from the 19th century. They can ponder a dried flounder, fresh caught in 1793. They can see the nose cone of a Cold War missile, an 1880 clothes wringer, a jar of 150-year-old Brazilian coffee beans, and a brass-framed octant made in London before the Civil War.

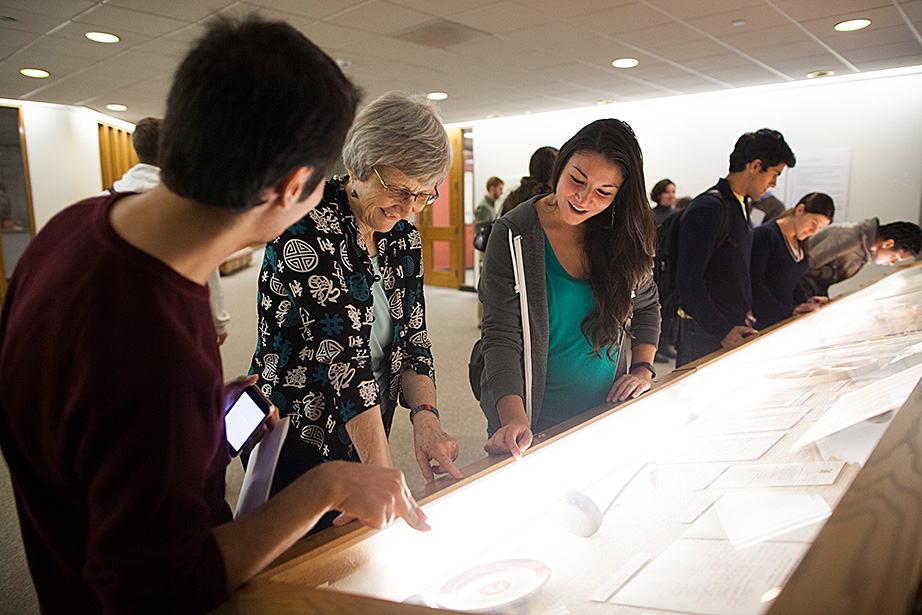

“A Case for Curiosity,” on view through next March in Harvard’s Science Center 371, was curated by students in this semester’s course USW30, “Tangible Things: Harvard Collections in World History.” First offered in 2011, the course signals a fresh, deep interest at Harvard in using artifacts to teach the humanities. Historian and co-instructor Laurel Thatcher Ulrich calls such artifacts “portals,” colorful tunnels into a past traditionally accessible only through the close study of texts.

In April, Ulrich was the keynote speaker at “University as Collector,” a conference sponsored by the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study and its Academic Ventures arm. She asked, “What happens when we take our curiosity to the curious things around us?” New fields of study open, said Ulrich, who presented a favorite example involving a Mexican tortilla acquired in 1896. Finding this artifact in a Harvard collection led her to economic botany collections of 70 or more years ago; to the origins of high-fructose corn syrup; and even to the history of Fritos corn chips. Unexpectedly, said Ulrich, “It was a transformative experience for me.”

Artifacts can help to uncover vanished eras. They offer insights into the economy, family life, gender norms, preferred food, and more. With close study, artifacts also can help students to understand the literature and history that emerged from such quotidian contexts.

Objects are lenses for seeing the past, said Jennifer L. Roberts, Elizabeth Cary Agassiz Professor of the Humanities. In old maps, for instance, “other forms of knowledge may be lurking,” she said at the Radcliffe conference, including insights into long-gone “craft, engineering, and material science.”

Such objects can also illuminate the recent past, said Joseph Pellegrino University Professor Peter Galison at the conference. In a video presentation, he showed a control panel from a Harvard cyclotron (1935–2002). Its myriad of tiny screens, toggles, and switches now seem straight out of a “Doctor Who” episode. But the panel is actually a record of what were once “the most advanced technologies in high-energy physics,” said Galison, director of the Collection of Historical Scientific Instruments.

At Harvard, using objects to study the humanities is a relatively recent development. Not so with science. Starting in the late 17th century, physics and astronomy were taught by means of “scientific apparatus,” beginning with a telescope donated to Harvard in 1672. Learning through objects also came naturally to art history, which began in earnest at Harvard in 1875.

But it wasn’t until the 1980s that object-based learning began in the humanities. Richard Wendorf, then head librarian at Houghton Library, encouraged faculty to use the library’s classroom spaces. “That’s been happening gradually,” said Leslie Morris, the Houghton’s curator of modern books and manuscripts. But in the past five years there has been “an explosion” of interest, she said. In 2014, there were 428 class sessions at Houghton.

Momentum is building for more objects-based learning. This semester, the FAS sponsored three panels on “active learning,” including an April 1 session on “Teaching with Collections.” Ulrich, Galison, and others took part in “Museum Conversations” on April 27, co-sponsored by the Harvard Museums of Science and Culture, a consortium whose mission champions the pedagogical value of objects. The reception was at the Harvard Semitic Museum, a University pioneer in teaching the humanities through objects and object making. (“It’s what we do,” said director Peter Der Manuelian.) On May 5, Ulrich brought her “scholarship of things” message to the Harvard Ed Portal.

This year, a new two-semester humanities course, “Colloquium: Essential Works,” included hands-on library visits. “It was the perfect last class,” said social studies concentrator Emily Rubenstein ’15, who joined classmates at the library in late April, where they examined books and manuscripts, including a Shakespeare first folio, letters of Virginia Woolf, and a first edition of James Joyce’s “Ulysses.”

In an era of reading on Kindles and laptops, the visit provided “a stronger connection to the book itself,” said Rubenstein. “It’s tangible.”

Looking, listening, reading to become culturally astute

How do people look, listen, and read? It’s the ability to do those tasks well that allows people to navigate the world, and encourages them to reflect, reason, and respond to what they find. Mastering these skills is at the heart of a new Harvard effort to help students become better cultural citizens.

Looking to reinforce the humanities and eager to reimagine a collaborative curriculum for today, Harvard administrators and faculty released three comprehensive reports in 2013 on the humanities landscape. Their recommendations included a call for clearer entry points into those areas for freshmen and sophomores. The result was a trio of “frameworks” classes on the arts involving looking, listening, and reading, to help undergraduates explore the human experience.

“When students arrive on campus they may not see a clear pathway into the study of the arts and humanities,” said Diana Sorensen, dean of arts and humanities, who requested the reports. The new courses offer “critical tools” for understanding messages in sound, pictures, and text, she said, and help students to develop the interpretive skills fundamental to humanistic inquiry.

The approach encourages instructors to view the humanities “not just as a set of separate disciplines and programs, but in a much more integrated way,” said Julie Buckler, professor of Slavic languages and literatures, who taught “The Art of Reading” this spring with Michael J. Puett, Walter C. Klein Professor of Chinese History. In the class, students read and interpreted literature, but they also examined historical narratives, visual materials, blogs, computer games, and graphic novels.

“The Art of Listening” tapped poetry and literature’s rich aural traditions and explored philosophical reflections on listening by Friedrich Nietzsche, Plato, and others. In “The Art of Looking,” a class on the world map touched on “geometry, geopolitics, and the histories of printing, navigation, and religion,” the syllabus said. A section on porcelain engaged “aesthetics, gender, food ways, labor, history, chemistry, espionage, and global exchange and translation.”

“We’ve tried very hard to present something more fundamental, something below the disciplines that will allow students to spring in many different directions,” said Jennifer L. Roberts, Elizabeth Cary Agassiz Professor of the Humanities, who helps lead “Looking.”

The courses have a modern mindset. As technologies evolve, Harvard educators said, new approaches to teaching need to do so too.

“Undergraduates these days live in a world that is saturated with new visual technologies,” said Robin Kelsey, the Shirley Carter Burden Professor of Photography, who developed “Looking” with Roberts. To reach students, Kelsey suggested, give the technologies they use “a kind of history,” and then discuss “the histories of various visual technologies throughout time.”

For one assignment, Kelsey and Roberts asked students to develop an iPhone app that could reproduce a daguerreotype, a 19th-century photographic technique that captures an image on a shiny metal plate.

The assignment illustrated a key feature of the frameworks courses: the art of making, which brings physicality to the classroom. In “Listening,” students stepped back in technological time to create a mix tape using cassettes and recorders. For “Reading,” students acted out scenes from playwright Samuel Beckett’s enigmatic “Waiting for Godot.” The undergraduates interpreted Beckett by making “all kinds of choices” with his sparse text, said Buckler. “It’s so obviously meant to thwart its reader’s search to impose some sort of unitary reading on it.”

Harvard’s rich collections are another integral part of the frameworks courses. Students view great artworks in the University’s museums, participate in close readings of texts in the libraries, and practice close listening during excursions to “sound-rich places around campus,” including sampling the Lowell House bells, said Alexander Rehding, Fanny Peabody Professor of Music, who has taught “The Art of Listening” with John T. Hamilton, William R. Kenan Professor of German and Comparative Literature.

Student Justin Dower recently declared a Romance languages and literatures concentration to complement his pre-med track. He said Rehding and Hamilton’s course “opened up the humanities at Harvard to me,” introducing him to the “careful reading, and observation, and listening” that they require.

Up next in the curriculum is “The Art of Living,” a fall course that will explore classical philosophical traditions. The frameworks courses, said Kelsey, are one of many “curricular experiments that are really bringing the Harvard curriculum into the 21st century in a variety of exciting ways.”