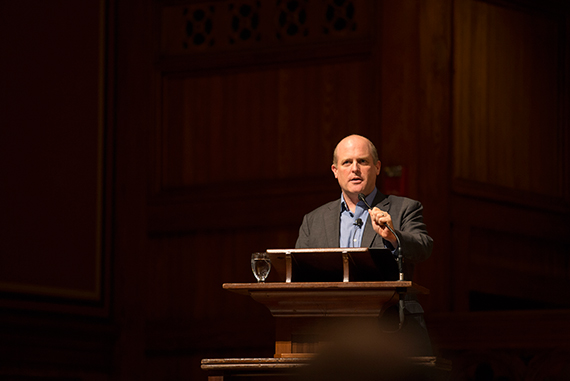

A panel of experts examined “Coping With Climate Change: How Will Boston Adapt?” during a HUBweek event at Sanders Theatre. Moderating the talk was Harvard University Center for the Environment Director Daniel Schrag (from left). The panel included Carl Spector, Boston’s director of climate and environmental planning; Atyia Martin, chief resilience officer for Boston; Robert Young, director of the Program for the Study of Developed Shorelines, Western Carolina University; and Harvard’s James McCarthy, Agassiz Professor of Biological Oceanography.

Rose Lincoln/Harvard Staff Photographer

To sample climate concerns, look at nature

HUBweek panel says recent past helps to show where action is needed, including in Boston

For those wondering what’s needed to face down coming climate-related disasters, the approach is simple, according to one expert: Just listen to nature. It’s screaming the answer.

“Every storm tells you where the problems are,” said Robert Young, director of the Program for the Study of Developed Shorelines at Western Carolina University. “Every storm is an opportunity to reimagine your community.”

Young told a panel on Wednesday that the problem isn’t that people don’t know which areas are vulnerable to natural disasters, or even — as climate-change science becomes more settled in the public’s mind — that they don’t understand the threat. It’s that they refuse to learn obvious and sometimes painful lessons.

“We repeatedly fail to take the opportunity to rebuild following storms in the way that makes the most sense,” Young said. “We do a terrible job at this.”

Young and other panelists at Harvard’s Sanders Theatre suggested changes to federal flood-insurance programs that now enable property owners to rebuild repeatedly on vulnerable sites, and they floated the idea of a rapid-buyout program that would offer to purchase damaged sites while owners are still deciding the best course forward.

The session, which focused on the Boston region’s need to adapt to meet the challenges of climate change, was sponsored by the Harvard University Center for the Environment and was part of HUBweek, a series of events highlighting the area’s strengths in art, science, and technology.

HUCE Director Daniel Schrag, the Sturgis Hooper Professor of Geology and professor of environmental science and engineering, moderated the event. Schrag said a discussion like Wednesday’s would have generated controversy a decade ago, when people pushing for climate action decried any talk of adaptation as taking away from efforts to reduce emissions. Today, Schrag said, it has become clear that both reducing emissions and adapting to climate change’s effects are needed.

Schrag cited Hurricane Katrina and Superstorm Sandy for delivering the kind of impact that may be expected in the future. In New York Harbor, the record storm surge at The Battery had stood at 11.2 feet in 1821. Sandy’s tide surge hit 13.8 feet. Schrag showed a photo of Manhattan after the power went out, which showed a single office tower lit up. The building, housing Goldman Sachs, had emergency generators located in areas not affected by flooding.

“To me,” Schrag said, “this is a postcard of the value of preparedness.”

The downpours that struck the Carolinas last week are another example. Media reports calling it a 1,000-year storm may be doing the public a disservice, Schrag said. First, records don’t go back far enough to know if that is a one-in-a-millennium event; second, because the climate baseline is shifting, this type of event may become more common.

James McCarthy, Alexander Agassiz Professor of Biological Oceanography and a member of the panel, drew a parallel between the recent rains and Boston’s record snowfall last winter. That occurred, he said, not because it was particularly cold, but rather because the ocean offshore was unusually warm, which put more moisture into the air. It’s the kind of scenario that could be repeated in a warming world.

Panelists Atyia Martin, Boston’s chief resilience officer, and Carl Spector, its director of climate and environmental planning, discussed the city’s planning efforts and work to engage the community in both understanding potential impact and thinking about responses. Spector said Boston already has taken steps to make its cooling centers — used in the case of extreme heat waves — more robust by mounting solar panels and battery backups.

The panelists agreed that the likelihood of clogged roadways, stranded travelers, and a lack of places to lodge even successful evacuees makes large-scale evacuation of the city an unattractive response. Instead, they said, plans should encompass how to manage the needs of those who shelter in place, or, in the case of evacuation, ways to make that succeed even for those facing challenges such as no vehicle or little money to pay for transportation or hotel costs.

The kind of large-scale hardening of Boston’s coastline that might shut out a surging ocean is likely to be prohibitively expensive, panelists said. Even so, the practice that put the city at risk — building in vulnerable areas — is continuing here and in cities across the country “one permit at a time,” Young said, since consumers hunger for waterfront property.

In the meantime, natural areas like marshes and barrier beaches that might help absorb some of a storm’s force are disappearing. Even after catastrophes like Sandy, rebuilding is occurring in the same places, ignoring the lesson that nature is trying to teach.

“Sandy told us where the highly vulnerable communities in New York and New Jersey are,” Young said.

In the end, Schrag said, it isn’t just the planners and experts who need to be involved to keep individuals safe. People have to take responsibility and concrete steps to protect themselves as well.

“How,” he asked, “are we going to be prepared when these events come to pass, which they will.

For more information, check out a digest of Harvard activities for the week here, or register to attend events at HUBweek.org.