The costs of inequality: When a fair shake isn’t

Harvard researchers, scholars identify stubborn tenets of America’s built-in inequity, offer answers

First in a series on what Harvard scholars are doing to identify and understand inequality, in seeking solutions to one of America’s most vexing problems.

It’s a seemingly nondescript chart, buried in a Harvard Business School (HBS) professor’s academic paper.

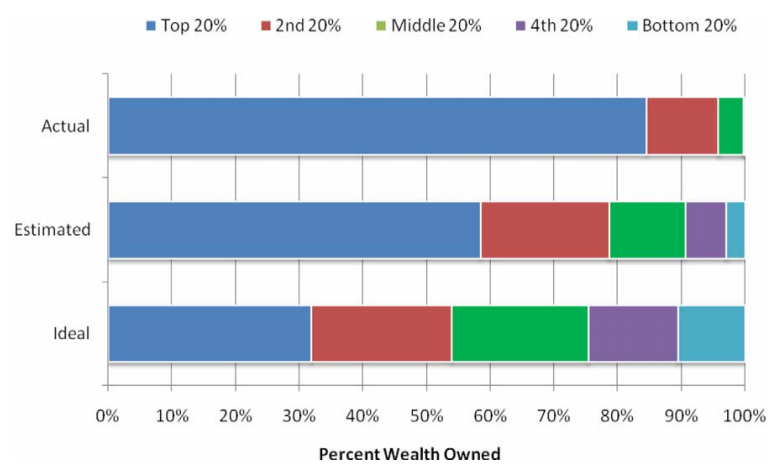

A rectangle, divided into parts, depicts U.S. wealth for each fifth of the population. But it appears to show only three divisions. The bottom two, representing the accumulated wealth of 124 million people, are so small that they almost don’t even show up.

Other charts in other journals illustrate different aspects of American inequality. They might depict income, housing quality, rates of imprisonment, or levels of political influence, but they all look very much the same.

Perhaps most damning are those that reflect opportunity — whether involving education, health, race, or gender — because the inequity represented there belies our national identity. America, we believe, is a land where everyone gets a fair start and then rises or falls according to his or her own talent and industry. But if you’re poor, if you’re uneducated, if you’re Black, if you’re Hispanic, if you’re a woman, there often is no fair start.

Inequality, of course, has become a national buzzword and a political cause célèbre in this election year. It’s been discussed everywhere in the recent past, from the State of the Union Address to Thomas Piketty’s best-seller to the lips of presidential candidates to Pope Francis’s encyclical “Laudato Si.”

Though the American public and politicians have just rediscovered the problem of inequality, the issue has long been an area of academic inquiry at Harvard, where research on its root causes crosses numerous disciplines.

Inequality in America has been on the rise in recent years, after dipping by some measures following the Gilded Age and the Great Depression. It was a reality when Harvard philosopher John Rawls wrote his seminal text, “A Theory of Justice,” in 1971. It was a reality when now-Harvard Kennedy School (HKS) lecturer Marshall Ganz organized farm workers in the Southwest in the 1960s and ’70s. It was a reality when Nancy Oriol, now dean for students at Harvard Medical School (HMS), founded the Family Van care program in 1992. It was a reality when Government Professor Jennifer Hochschild wrote “Facing Up to the American Dream” in 1995, and when other faculty members penned books and articles on the problem’s many facets. And it was an expanding reality in 2011, when HBS Professor Michael Norton published that rectangular graph, in a study that also showed that Americans really don’t know how unequal the United States is — and that, given a blind choice, they’d rather live in Sweden, thank you very much.

One measure of American inequality is the percentage of the nation’s overall wealth owned by different parts of the population. The graphic above shows that the richest 20 percent of the country owns 88.9 percent of the nation’s wealth, while the bottom 40 percent owes more than it owns.

Graphic by Judy Blomquist/Harvard Staff

A blizzard of statistics illustrates the problem and, with each monthly release from the Census Bureau, the Bureau of Labor Statistics, or any number of think tanks, the pile of reports grows higher. Their by-now-familiar theme is that the rich have gotten richer — dramatically so — in recent decades, while the poor have gotten poorer. And the middle class has just been hanging on.

Wages for most relatively stagnant

The details show that real wages for most U.S. workers have been relatively stagnant since the 1970s, while those for the top 1 percent have increased 156 percent, and those for the top 0.1 percent have increased 362 percent, according to a report by the Economic Policy Institute.

Those trends resulted in the poorest 20 percent of Americans receiving just 3.6 percent of the national income in 2014, down from 5.7 percent in 1974. The upper 20 percent, meanwhile, received nearly half of U.S. income in 2014, up from about 40 percent in 1974, according to Census Bureau statistics.

But some analysts, such as Hochschild and Piketty, the French economist, say the area of greatest concern is overall wealth, not income alone.

“From a poverty perspective, income means a lot — making $15,000 versus $20,000,” said Hochschild, who directs the HKS-based Multidisciplinary Program in Inequality and Social Policy. But “from an inequality perspective — writ large — it’s about wealth. … As a ’60s kid, I care a whole lot about ownership of the means of productivity.”

In his 2013 best-seller “Capital in the Twenty-First Century,” Piketty argues that wealth is critically important because capital grows faster than the economy. That means that those who hold capital — assets like money, stocks, real estate — will see their wealth grow faster than those managing on wages alone. Over time, that concentrates society’s wealth into fewer hands.

America today appears to illustrate this process in action. Though the wealthiest 20 percent earned nearly half of all wages in 2014, they have more than 80 percent of the wealth. The wealth of the poorest 20 percent, as measured by net worth, is actually negative. If they sell all they own, they’ll still be in debt.

“Inequality, it’s not just about wealth, it’s about power. It isn’t just that somebody has some yachts, it’s the effect on democracy. For me, the big issue is the power problem. … I think we’re in a really scary place.”

Marshall Ganz

The widening wealth gap isn’t just a problem for the poor, census figures show. The median net worth of some 60 percent of Americans fell between 2000 and 2011, while that of the upper 40 percent increased.

So what happened? Tax rates for the wealthy have fallen, globalization has changed the world’s and the nation’s economies, and rapidly changing technology has transformed the workplace. While those factors are in play, Norton said that nothing’s been proven yet as a dominant cause. To Hochschild, the problem’s roots lie in poverty, exacerbated by racism. The poor usually have worse health and education, leading to low-paying jobs and substandard housing, conditions that tend to be worse if you’re Black, Native American, or another ethnic minority. To Ganz, a senior lecturer in public policy, that’s not an accident, and it boils down to two words.

“Political failure,” said Ganz. “I think the galloping inequality in this country results from poor political choices. There was nothing inevitable, nothing global. We made a series of political choices … that set us on this path.”

Ganz pointed to a broad deregulation push that started with fiscal restraint under President Jimmy Carter and a budget-cutting campaign to “starve the beast” of government that began with President Ronald Reagan. Collectively, the two administrations eviscerated the government’s ability to act and function as a check on private wealth, he said.

Ganz also blamed a suite of changes that eroded the power of labor unions. Their clout fell as legal protections for organizing activities eroded, beginning with the Taft-Hartley Act in 1947 and continuing since. Without that protection, employers were able to pressure organizers and reduce the likelihood that unions would take hold and thrive.

“It takes a lot of courage to say — when your employer holds all the power — ‘We want something better,’” Ganz said. “This has been a real political success story for the conservative movement and private management.”

Union membership down almost half

U.S. union membership has fallen by almost half since 1983, from one in five U.S. workers to just over one in 10 in 2014, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Public union membership has fared better than private labor unions, whose membership has fallen to just 6.6 percent of the workforce. Recent anti-union activities in some states have focused on those public-sector groups.

Despite their declining numbers and influence, the unions’ effect on wages remains clear. Nonunion wages in 2014 averaged $763 per week, just 79 percent of union members’ $970 per week, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Ganz said that the impact of falling union membership is felt not just in workers’ pocketbooks, but in the halls of power, and that is the change that troubles him the most.

“Inequality, it’s not just about wealth, it’s about power,” Ganz said. “It isn’t just that somebody has some yachts, it’s the effect on democracy. For me, the big issue is the power problem. … I think we’re in a really scary place.”

To Lawrence Katz, the Elisabeth Allison Professor of Economics, the problem of inequality in income, wealth, and political power is exacerbated by another issue. America’s vaunted economic mobility has become decidedly less so, making it increasingly likely that where you start out financially is where you’ll wind up.

Surveys of attitudes toward wealth conducted by Norton, the Harold M. Brierley Professor of Business Administration, show that while Americans believe their nation is too unequal, they also believe that some inequality is good. Workers, after all, should benefit from their own toil. The single mom who works two jobs and puts herself through school should be celebrated when she lands a better job, buys a nicer car, and moves to a better neighborhood. To a great extent, that’s the hallowed American way — when it’s possible.

Thomas Scanlon, the Alford Professor of Natural Religion, Moral Philosophy, and Civil Polity, said it’s important to think hard about why high inequality is a problem at all. That’s because the conclusions reached may underpin action. If you’re wealthy and you’re facing a hefty tax increase, or you’re a business owner bracing for a minimum-wage hike for your employees, the reason why you’ll get to keep less money and someone else will get more matters greatly.

“Philosophers are in the business of thinking hard about issues, identifying the relevant factors,” Scanlon said. “There is widespread concern about the increased gap between ‘the 1 percent’ and the rest. But it is important to be clear exactly what is bad about this.”

Altruistic motives underlie much of the national debate on the topic. One argument says the wealthy should sacrifice some of their gains to help the poor. But Scanlon said this is not the only valid reason to worry about national inequality. Workers aren’t charity cases. Instead they’re partners in the production of goods and services in this country and are entitled to a fair share of the system’s benefits, Scanlon wrote in a recent article. He agrees that inequality also results in distributing political power inequitably, making governmental institutions more unfair, and undermining the integrity of the economic system. All of that raises a key question for workers: Why bother pushing so hard?

“If an economy is producing an increasing level of goods and services, then all those who participate in producing those benefits — workers as well as others — should share in the result,” Scanlon wrote. “No one has reason to accept a scheme of cooperation that places their lives under the control of others, that deprives them of meaningful political participation, that deprives their children of the opportunity to qualify for better jobs, and that deprives them of a share of the wealth they help to produce. The holdings of the rich are not legitimate if they are acquired through competition from which others are excluded, and made possible by laws that are shaped by the rich for the benefit of the rich. In these ways, economic inequality can undermine the conditions of its own legitimacy.”

“Talent is evenly spread throughout our country. Opportunity is not. Right now, there exists an almost ironclad link between a child’s ZIP code and her chances of success.”

James Ryan

Others at Harvard have been pondering inequality as well, examining the issue through their own disciplinary lenses. Oriol, as director of obstetric anesthesia at Harvard-affiliated Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in the ’80s, saw firsthand the disparities in infant mortality among the poor in Boston’s neighborhoods.

“The discussion was: Why was infant mortality, in the shadow of some of our greatest hospitals, as bad as in some developing countries? As an obstetric anesthesiologist, I saw this, and I would hear from my patients how this came to be,” she recalled. “And it just seemed wrong.”

By the early ’90s, Oriol’s effort to address the problem through a mobile medical clinic, now HMS’ Family Van, brought health screenings and referrals to the nearby neglected neighborhoods. But the van staff quickly learned that infant mortality wasn’t the only problem.

“Infant mortality was simply a sign of a community in distress,” Oriol said. “The issue was poverty and what I call being medically disenfranchised. It was all the issues of life. It was homelessness, it was not having a job — just everything.”

Over at Harvard Divinity School, Dan McKanan, Ralph Waldo Emerson Unitarian Universalist Association Senior Lecturer in Divinity, is examining the issue from a moral standpoint. He said society’s economic fruits — born most recently on a wave of automation and technical sophistication — make it possible to improve the lives of the poor beyond what was possible previously.

One way to do that, he said, would be to guarantee all citizens a minimum income. This would free millions from what can become “wage slavery,” he said, and allow people to follow passions and creative urges. McKanan acknowledged that such a scheme — which might be accomplished by expanding Social Security — is politically unlikely, but said it is the role of academics to think deeply about how to create a more moral and just society that works better.

Though the resultant redistribution of wealth represented by McKanan’s idea would be too extreme for many Americans, Norton’s survey work on the topic does show that Americans want a more equal society than exists now.

A surprising central finding of Norton’s research is that we really don’t know how unequal the United States is. In a 2011 study, conducted with Duke University’s Dan Ariely, Americans consistently underestimated just how unequal the nation is and said their preferred wealth distribution ― while preserving some inequality — is more leveling than their inaccurate understanding of the current state of affairs.

In a blind test, we’ll take Sweden

Those surveyed guessed that the top 20 percent of Americans own 60 percent of the wealth, not the more than 80 percent they actually have. Further, when shown three unlabeled wealth distributions ― one completely equal, one dramatically skewed (and in fact representing divisions in the United States today), and a third using the income distribution of modern Sweden — 92 percent preferred the Swedish model.

“We want to be in Sweden, all subgroups want to be in Sweden, if people could distribute the wealth any way they wanted,” Norton said. “Everyone is OK with rich and poor, but almost no one prefers the current state of the world.”

But that agreement in a controlled study doesn’t translate to easy political fixes, Norton said.

“We had the perhaps naïve idea that we could show people the reality, and their attitudes and behavior would change,” Norton said. “But I’m a behavioral scientist, and we know that information alone is often not enough. It’s not an information problem, it’s an action problem.”

It’s not surprising that liberals say there’s too much inequality, or that the very poor believe the gap between the rich and themselves is too big. But Norton said most conservatives and the wealthy also agree that the gap is too big. The problem, he said, is that the different camps disagree on solutions. A minimum wage hike to some is a direct way to get money in people’s pockets. To others, though, it’s a way to get someone’s job taken away. Another problem, he said, is that many people distrust the government — which many blame for the dichotomy in the first place — to fix it.

Without meaningful action, American inequality will continue to be felt not just in the economic arena, but in many other facets of American life, including criminal justice, health, and education, among others.

When Norton surveyed HBS alumni on the subject as part of the School’s 2015 Survey on U.S. Competitiveness, many respondents pointed toward education as both a cause of inequality and a potential solution.

That’s a point of view that Harvard Graduate School of Education Dean James Ryan understands. The ideal of American education is equal quality for all, but it has never been achieved, Ryan said in an interview, and understanding why that is true, and how to change it, is the core mission of the School he leads.

“Talent is evenly spread throughout our country. Opportunity is not,” Ryan said. “Right now, there exists an almost ironclad link between a child’s ZIP code and her chances of success.”

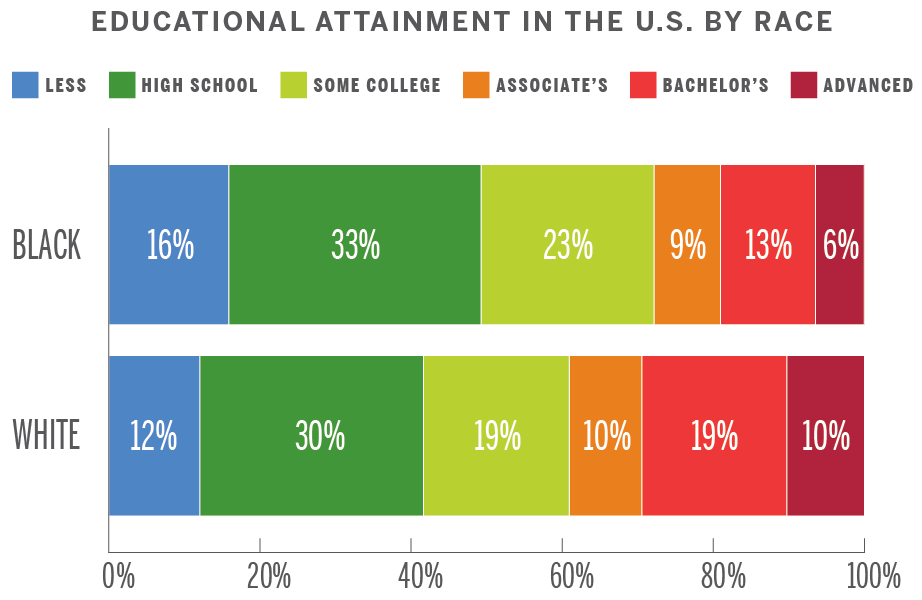

Some progress has been made. Minority educational achievement has improved over the past 40 years, and achievement gaps have narrowed some between minorities and whites, and between women and men, according to the four-year report card from the National Assessment of Educational Progress. But gaps persist. The 44-point reading gap that existed between Black and white 9-year-olds in 1971 had narrowed by 2012, but still stood at 23 points, according to the report.

That story is mirrored in higher education, with some gains but persistent gaps. The proportion of associate’s, bachelor’s, master’s, and doctorate degrees awarded to Blacks and Hispanics all increased, though progress slowed the higher the degree, according to the National Center for Education Statistics. In the 2009-10 academic year, Black people earned 14 percent of all associate’s degrees, on a par with their 13.2 percent representation in the population. But they earned only 10 percent of bachelor’s degrees, 12 percent of master’s, and 7.4 percent of doctorates.

Those figures also mask the fact that while Black women have progressed and earn disproportionately more of those degrees, the gaps for Black men have been slower to close, according to a 2012 report from the National Center for Education Statistics.

At the same time, Black men are overrepresented in U.S. jails, according to a 2014 report by the U.S. Department of Justice. At a time when society, in the wake of racial flare-ups in Ferguson, Mo., and elsewhere, has been questioning just how evenhanded its law enforcement practices are, African American men make up 37 percent of the prison population, compared with 32 percent white and 22 percent Hispanic. In the general population, Blacks make up 13 percent, whites 62 percent, and Hispanics 17.

Possible solutions to inequality:

- Better educational prospects

- Political willingness to act

- Standardized health care

- Balanced tax policies

- Improved economic mobility

- Employer-worker partnerships

Bruce Western, the Guggenheim Professor of Criminal Justice Policy, professor of sociology, and director of HKS’ Malcolm Wiener Center for Social Policy, is among the Harvard faculty members examining the problems of dramatic inequality in the criminal justice system. In today’s America, Western said in an interview, an outsized two-thirds of African American men with low levels of schooling will spend time in prison, losing years when they could be building careers while gaining a stigma that can undercut the rest of their lives.

Archon Fung, academic dean and Ford Foundation Professor of Democracy and Citizenship at HKS, said scholars are approaching the issue from many angles. Some are concerned with what he termed “the floor,” the problems of those in the bottom 10 or 20 percent, while others are concerned with the gulf between rich and poor.

“Some people are more floor people, and some are more gap people,” Fung said.

A third focus, Fung said, concerns mobility and opportunity, or how easy or hard it is to move between social classes.

Fung himself works on democracy and participation. Through that lens, he’s concerned with the floor, the gap, and how political participation and influence may be restricted for those at the bottom who lack influence.

What is clear, Fung said, is that those who are well-off simply have more: more money to donate to candidates, more time to volunteer in their communities, and more resources generally that allow them to participate and thrive in civil society. All of that, he said, is reflected in studies that have shown that government is more responsive to those at the top of the socioeconomic ladder.

In the end, Fung said, “Preserving the integrity of our democracy may be the most important reason to address poverty and inequality.”

Gazette staff writers Colleen Walsh, Christina Pazzanese, and Corydon Ireland contributed to this report.

Illustration by Kathleen M.G. Howlett.

Next Tuesday: political and economic inequality