Oula Alrifai, A.M. ’19, and her brother, Mouhanad Al-Rifay, are releasing “Tomorrow’s Children,” a documentary about Syrian child refugees trying to survive in Turkey.

Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

The not lost generation

Syrian asylees release documentary to highlight struggles of child refugees

In 2005, years before Donald Trump’s travel ban, Europe’s refugee crisis, or Barack Obama’s “red line,” Oula Alrifai and her family were granted political asylum from the Syrian government, without ceremony. It was the day before her 18th birthday.

“That was a depressing day,” said Alrifai, a master’s degree candidate with the Center for Middle Eastern Studies at Harvard University. “I had to leave everything behind.”

The Al Rifa’i family had fought for democracy in Syria for generations. Many of their friends and relatives had been imprisoned, killed, tortured, or exiled for speaking out against the government of Bashar al-Assad. Alrifai and her brother, Mouhanad Al-Rifay, were already showing a penchant for dissidence at school, and her parents began receiving death threats from government agents. They quickly fled to Washington, D.C., where Alrifai said they were among the city’s first asylees from Syria.

“We were lucky,” said Al-Rifay, who was 14 at the time. “I feel like life protected us for some reason.”

Driven by the same instincts that made them troublemakers in Syria, she and her brother continued their mission to bring democracy to their home. With the Tharwa Foundation, Alrifai contributed to a series of online documentaries called “First Step,” which called for a nonviolent revolution in the country. Two years later, the siblings founded the Syrian-American Network for Aid and Development (SANAD), dedicated to providing support and financial assistance to families escaping the conflict.

When the refugee crisis became headline news in 2013, Alrifai and Al-Rifay traveled to Turkey’s Anatolia region to look for Syrians trying to rebuild their lives. They found people stuck in a liminal stage of immigration, with thousands of children — most from Aleppo, a focal point of the civil war — working as laborers from dawn until dusk, for just a few dollars a day. None of them were in school.

“They have to survive and help their families even though they’re between 10 and 13, or even younger,” said Al-Rifay. “They work every day, literally every single day … they have to skip work to be normal [kids].”

With the children’s permission, the siblings began taping their talks. Alrifai said she focused on questions, using neutral language to ask the children what they thought about the war, Assad, and the rebels. “I wanted to know what they thought without guiding them. We wanted to give these kids a voice, because no one was talking about them,” she said.

The two compiled a documentary, “Tomorrow’s Children,” with Alrifai as executive producer and Al-Rifay as director. The film is comprised of six vignettes, each devoted to one child they interviewed. The documentary is currently in postproduction, and expected to be released in early 2018.

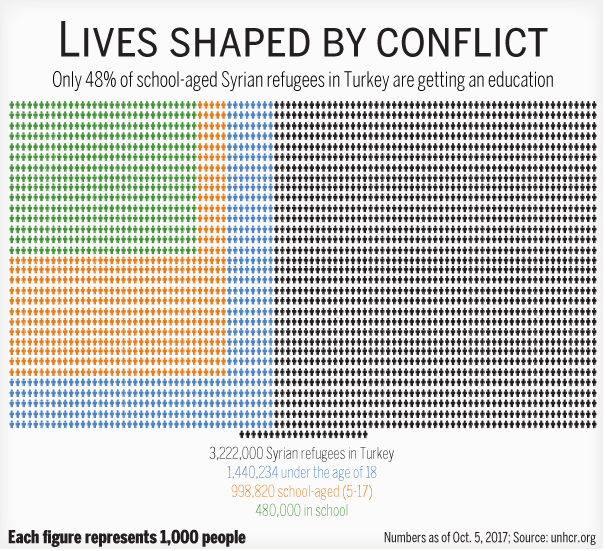

More than 5 million Syrian refugees have been registered by the U.N. High Commissioner for Refugees since the conflict began, nearly half of them younger than 18 years old. Only 20 percent of those children get counseling, and less than 5 percent are continuing their education. Turkey, with which Syria shares a 511-mile border on its north, has taken the majority of these refugees, including 1.4 million children. Very few of the children go to school, and many of them are forced into a life of exploitative labor, according to the U.N. Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (UNOCHA).

“These kids are completely pessimistic. They don’t see anything positive in life,” said Al-Rifay. “That’s not right for a 12-year-old.”

One boy, Shrivan, whose neighborhood in Aleppo was evacuated when the Free Syrian Army invaded, expressed disdain for the rebel group. Shrivan had been a high performer in school, but had to start working only a week after escaping shelling and sniper fire.

“In his mind, they brought the problem into his life,” said Al-Rifay. “Now he sees the bigger picture, but at the time, he was someone who left because of the opposition.” With the help of SANAD’s education fund, Shrivan was able to stop working and is back in school.

“I feel like my whole struggle was convincing people that Syrians are people,” Al-Rifay said. “We should listen to these kids because they’re going to be adults soon. And if we don’t do anything, they’re going to be taken to the other side.” Radical groups take advantage of children, he said, citing a boy who, when asked what he would do to make Syria better, said he would go to jihad.

“He’s a little kid. He doesn’t know what jihad is,” Alrifai said.

“When someone is that age … they don’t know what they’re saying,” Al-Rifay agreed, “and then a terrorist comes along, says ‘Oh, hey, we believe in jihad, too,’ and they make him into a terrorist.”

According to the UNOCHA, children are being recruited into militant groups in 90 percent of surveyed locations where Syrian refugees have settled.

“What we went through is not comparable to what they went through,” Alrifai said. It is the relative ease with which the Al Rifa’i family was granted residence and recently citizenship that drives the siblings most. They are well aware that if they had fled Syria today instead of 12 years ago, they would not have been welcomed so readily — if at all.

“I’m Syrian and people should know that that doesn’t mean we’re terrorists. We’re refugees but we’re not coming to take your jobs,” she said. “We’re not radical Islamists who want to blow up places in America. This whole package that was created about Syria is just unbelievable. What [people] see on CNN and in newspapers is ‘terrorists and Syria,’ and now thanks to [Trump’s travel ban], it’s even worse.”

Though Alrifai sees little hope of the war ending with Assad’s ouster and the return of democracy, she said there is still hope for the children to reach their full potentials. Invest in these kids now, she said, because otherwise there will be a much steeper price down the line.

“You can’t be numb to it. They are the future generation and leaders of Syria.”