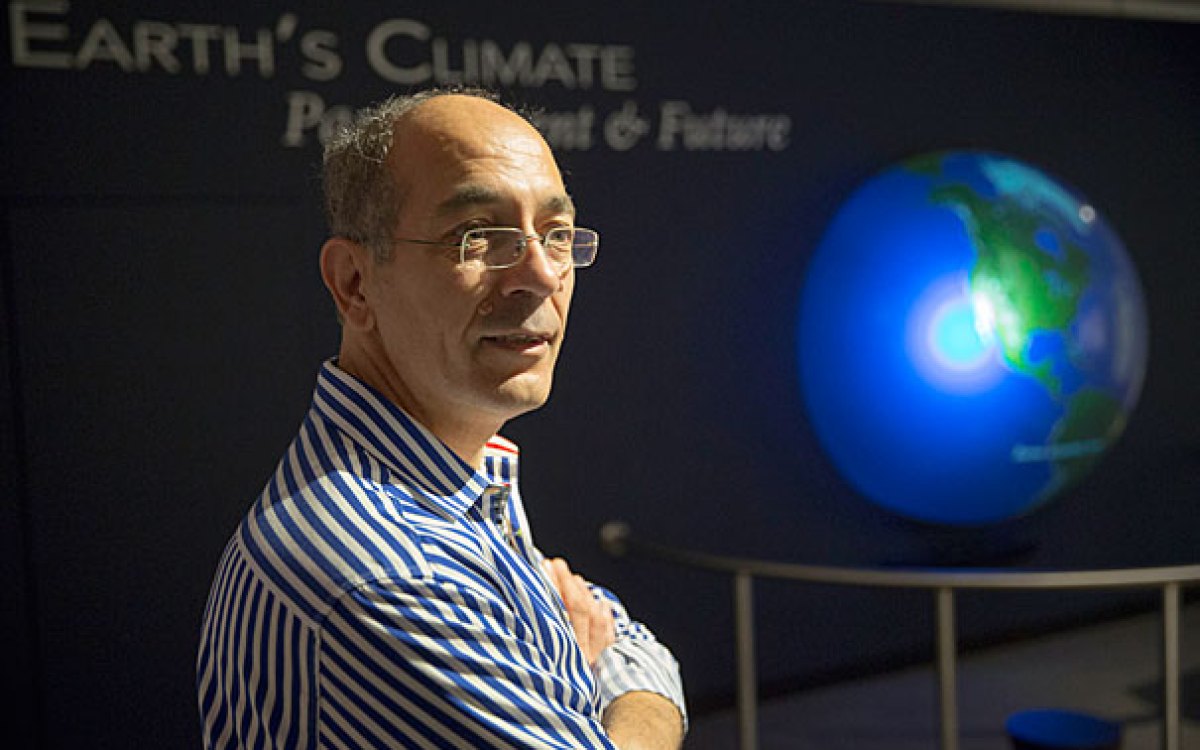

Visiting Professor Steven Handel says America’s coasts will change in the coming decades as sea levels rise, but landscape design, married with knowledge of native plants, can ensure that both human and natural needs are met.

Rose Lincoln/Harvard Staff Photographer

Transforming the ‘coastal squeeze’ from climate change

Landscape rehabilitator Handel proposes adapting pragmatically to sea-level rise

Analysts call it “the coastal squeeze,” but for plant and animal communities bordering urban and suburban seashores, another word could apply: extinction.

Though the Earth’s seas have risen and fallen many times over the planet’s lifetime, the man-made changes occurring now and the larger ones anticipated in the near future are different, says Steven Handel, a visiting professor in landscape architecture at Harvard’s Graduate School of Design.

The reason, he says, is because humans have built roads and houses and other hard, immutable structures along the coasts. And what people may view as scenic coastal roadways, the natural communities of plants and animals may experience as terminal barriers, blocking their migratory response to rising seas.

“Can these [natural] zones migrate when behind these zones is us — our sidewalks, roads, homes, factories, power stations, and yuppies jogging?” Handel said. “There’s no open land here, no open soil for these higher [ecosystem] zones to move to. This is civilization. We call this problem the coastal squeeze.”

But Handel, a plant ecologist who is visiting Harvard from Rutgers University, where he is distinguished professor of ecology and evolution, said all doesn’t have to be lost. Incorporating understanding of plant characteristics with smart design can produce alternatives that preserve natural communities and human use of a landscape endangered by sea-level rise that Handel said could — under pessimistic scenarios — top 31 inches by mid-century.

About a dozen years ago, Handel became interested in how natural processes could be harnessed to improve degraded, damaged, and abandoned sites dotting city landscapes.

He teamed up with landscape architects to transform the Fresh Kills Landfill in Staten Island and an all-but-abandoned former commercial port area near the Brooklyn Bridge. Both areas have been restored to their natural state and are habitats where native plants attract birds and other wildlife. And humans by the thousands also come to enjoy the park-like settings.

Other projects Handel has been involved in include a site in Beijing that was restored in preparation for the 2008 Summer Olympics, and California’s Orange County Great Park, fashioned from a decommissioned Marine Corps air station.

Handel spoke Tuesday evening at Harvard’s Geological Lecture Hall at an event sponsored by the Harvard Museum of Natural History (HMNH) and co-sponsored by the Association to Preserve Cape Cod. The talk was introduced by Jane Pickering, executive director of the Harvard Museums of Science and Culture, of which the HMNH is part, and by the association’s executive director, Andrew Gottlieb.

Handel used several projects as examples of how smart design can transform landscapes. Some buttress existing sites against coming changes even as they incorporate natural features, by encouraging sand dunes on previously flat beaches, and planting native, salt-tolerant trees and grasses. Other plans concede that the sea is likely to reclaim certain areas, such as barrier islands and some coastal homes, and recommend moving residents inland and converting the endangered sites to day and recreational uses.

The approach Handel described begins with accepting that the seas will rise. It takes projections for how sea levels will change familiar landscapes and moves forward from there, looking for opportunities such as inland water bodies and waterways that may soon be brackish, making them potential sites for future salt marshes. Newly engineered marshes can replace those drowned by the rising tide, buffer storms, and provide breeding grounds for fish and birds. Other opportunities lie in brownfields and abandoned sites that could be rehabilitated into places where communities meet the sea and around which fresh development can grow.

Homeowners living near the coast can help as well, Handel said, by substituting traditional landscape plantings and mown lawns with natural coastal plantings, like beach plum and other species selected both for their beauty and because they’re native.

“We want to tell people, ‘You’re 10 blocks from the bay, you’re part of the bay ecosystem,’” Handel said.

Unfortunately, everything can’t be saved. Though in the past it’s been possible to rebuild coastal homes wrecked by storms, rising seas and stronger storms will make those projects less practical, forcing some homeowners to move. Even natural communities not bounded by human development may not be able to disperse seeds and adapt inland as fast as the seas come up.

On Cape Cod, Handel pointed out that early maps show the land around its tip, near Provincetown, shifting even without the powerful forces unleashed by climate change, so that’s one place where more change can be expected. In addition, the Cape’s characteristic sand dunes will become even more vulnerable to erosion from the powerful surf.

How those and other changes will unfurl is uncertain, but the fact that change is coming isn’t, he said.

“The past is not prologue,” Handel said. “What we know from our youth and from today will not remain. That’s the one thing that we know for sure.”