Joseph Connors, professor of history of art and architecture, took listeners on a virtual tour of two of Rome’s most iconic spaces, the Piazza Navona and the Piazza San Pietro. Danielle Carrabino, an associate research curator in European Art at the Harvard Art Museums, assisted Connors on the exhibit.

Rose Lincoln/Harvard Staff Photographer

A detailed narrative of Rome

‘Eternal City’ professor notes papal influences, legacy of Bernini in Harvard Art Museums lecture

Known as the “Eternal City,” a label that underscores its long history of both tests and triumphs, Rome is simultaneously the stuff of fantasy and fact, legend and legions, myth and matter. Once the center of an empire that spanned the Mediterranean and much of Western Europe, the Italian capital speaks through its architecture as a giant of history and influence.

On Thursday, Joseph Connors, a professor of history of art and architecture, took his listeners on a virtual tour of two of Rome’s iconic spaces, the Piazza San Pietro, also known as St. Peter’s Square, and the Piazza Navona. In each venue, Connors said, visitors see the influence of papal directives and desires alongside the artistic brilliance of Gian Lorenzo Bernini, an Italian sculptor and architect largely responsible for defining the city’s 17th-century look.

Connors’ Harvard Art Museums talk was a companion to the exhibit “Rome: Eternal City,” which features a range of etchings and drawings of 17th- and 18th-century Rome and has served as a teaching tool for his current undergraduate course of the same name.

In the Piazza Navona, built atop the Stadium of Domitian, Pope Innocent X — “from whose anger no one was immune,” one of his minsters reportedly said — wielded a major influence on the look of the square. Eager to expand his small family palace next to the piazza, he acquired several adjoining palaces and razed others, making way for the redesign of the medieval St. Agnes church, converting it into “the locus of a great family chapel.”

Bernini’s iconic Fontana dei Quattro Fiumi, or the Fountain of the Four Rivers, is another highlight of the square, Connors noted. A Roman obelisk covered with Egyptian inscriptions “sits atop a tremendously daring base” featuring vivid caverns, rocks, animals, plants, and four massive figures representing four major rivers of the world.

Connors believes Bernini looked beyond Rome, to the work of Flemish artist Peter Paul Rubens, when designing his 1651 fountain. In a bit of detective work, the art historian studied a book in Harvard’s Houghton Library containing Rubens’ prints. The works, which depict the “joyous entry” in 1635 of Cardinal Infante Ferdinand, the ruler of Spanish Netherlands, into Antwerp as its new governor, include images of temporary stages and arches erected for the celebration that were covered with Rubens’ designs.

One arch contains striking similarities to the Italian fountain, including a range of mysterious creatures, trees, coins, a lion hiding in a grotto, and four rivers. Bernini was “really looking for stimulation” said Connors.

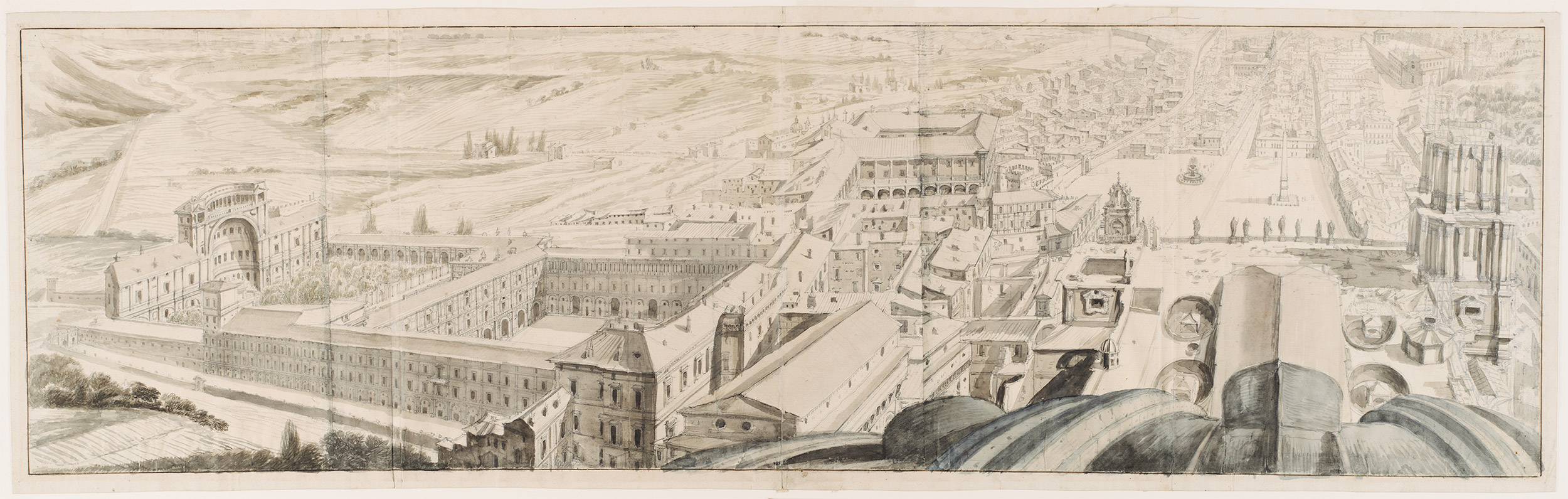

Israël Silvestre, Panorama of the Vatican from the Dome of St. Peter’s Basilica, 1641. Graphite, gray and brown wash, and watercolor over traces of black chalk. Harvard Art Museums/Fogg Museum, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Philip Hofer, 1961.7.

Harvard Art Museums; © President and Fellows of Harvard College

Those seeking more of Bernini’s work won’t need a ticket to Rome. On the museums’ second floor, in the small glass gallery that faces out onto Le Corbusier’s Center for the Visual Arts, are a series of clay sketches, or bozetti, by the Italian master. The collection includes several models of both the marble angels that adorn the Ponte Sant’Angelo, the bridge that spans the Tiber River near the Vatican, and the bronze statues that can be found kneeling at the Altar of the Blessed Sacrament in St. Peter’s Basilica.

And for a closer look at Rubens, museumgoers can visit the museums’ Northern Baroque gallery, where “The Voyage of the Cardinal Infante Ferdinand of Spain from Barcelona to Genoa in April 1633, with Neptune Calming the Tempest,” a preparatory oil sketch also created for the 1635 Antwerp celebration, is on view.

According to Connors, Bernini’s designs and the influence of the Holy See were no less central to the look of the Piazza San Pietro. Worried the papacy’s authority was in decline, Pope Alexander VII “thought he would compensate by a frenetic program of building to show that Rome really was the capital of the world.”

The architect Carlo Maderno aided in that effort, said Connors, extending the façade of St. Peter’s Basilica on either side with the creation of bell tower bases in 1618. Enlisted by Pope Urban to embellish the towers with an elaborate design, Bernini began work on the additions. But in 1641 cracks sparked fears the structures would topple, and Bernini’s work was demolished.

Fortunately, the artist’s signature design, the massive set of semicircular colonnades that frame the open piazza and lend it form and function, remain for tourists, pilgrims, and locals to enjoy.

The set of colonnades was an enclosure built “to contain crowds, but it’s not a suffocating enclosure,” said Connors. “The Bernini idea is you can breathe — crowds of enormous magnitude can move in and out easily. It’s a psychological container rather than a physical container,” and one of the world’s great gathering spaces.

The lecture was part of a series of museum-sponsored events to honor the 500th anniversary of the canon’s house of the 16th-century church of San Biagio, in Montepulciano, Italy, after which the museums’ Calderwood Courtyard is modeled.