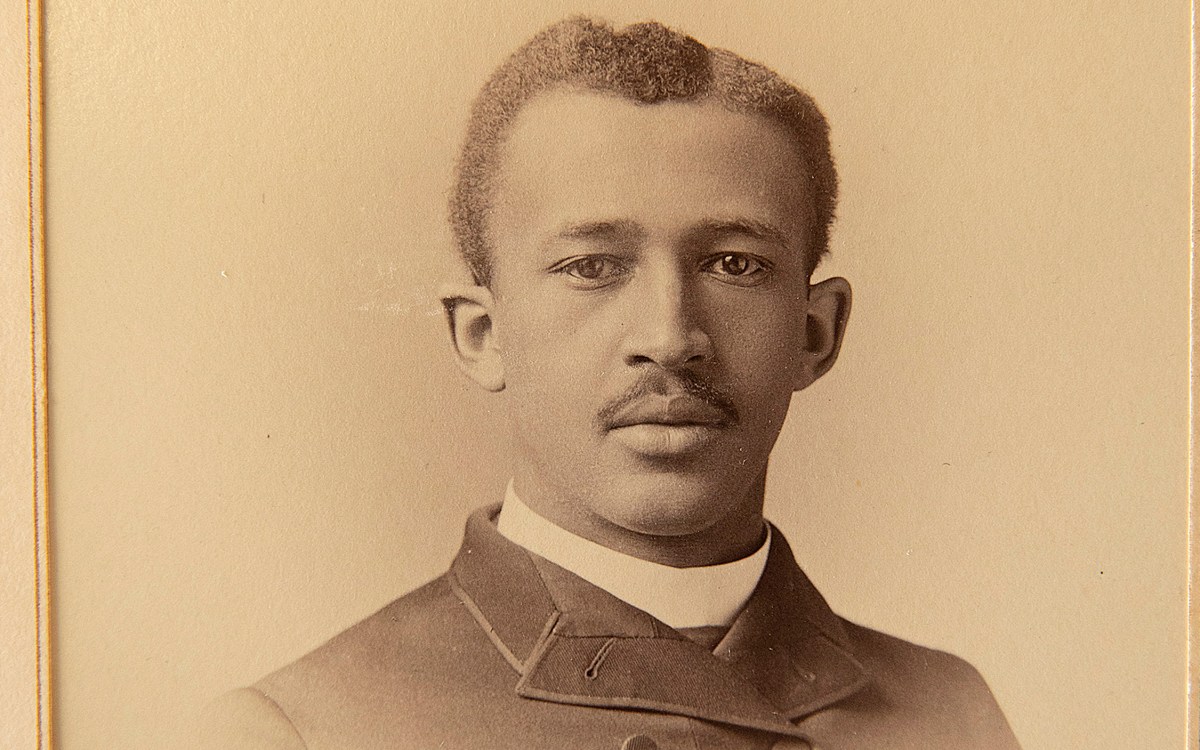

W.E.B. Du Bois addresses the World Congress of Partisans of Peace in 1949.

AP file photo

Du Bois as eminent sociologist

He expanded his field in major ways, often without credit or recognition, researcher says

If knowledge is power, then the scientific method, rigorously applied, can be a liberating force for social change — which explains, argues Aldon D. Morris, professor of sociology at Northwestern University, why the denial of W.E.B. Du Bois’ groundbreaking work in sociology is not merely an affront to a historic figure but a larger, societal attack on justice, equality, and science itself.

Giving the keynote speech at “Scholarship Above the Veil: A Sesquicentennial Symposium Honoring W.E.B. Du Bois” on Friday evening, Morris discussed DuBois’ role as a founding father of American sociology. In an impassioned talk from the pulpit of Cambridge’s University Lutheran Church, Morris argued how the scholar’s work has been systematically ignored for decades. In a larger context, he depicted this as a racist choice that has had implications for his field of scholarship, for academia, and for American society.

Drawing from his award-winning 2015 book, “The Scholar Denied: W.E.B. Du Bois and the Birth of Modern Sociology,” Morris traced how, as early as 1898, Du Bois, the first African-American to earn a Ph.D. from Harvard, was conducting important sociological research with a team of fellow African-American scholars at Atlanta University. (Du Bois would also write 1903’s seminal “The Souls of Black Folk” at Atlanta.)

During his long life, Du Bois was a sociologist, Civil Rights activist, historian, educator, editor, and outspoken public intellectual.

Applying rigorous methods, Du Bois’ studies and subsequent writing treated sociology as a science, employing empirical research and quantitative as well as qualitative analysis. This was in contrast to the prevailing method at the time of what Du Bois called “car window” sociology, in which observations were so superficial that the analyst might have merely driven by without taking the time or effort to understand the community he (for it was almost always a he) was theoretically studying.

Some such lazy scholarship was institutionalized and accepted in part because it didn’t threaten the status quo, said Morris. Supported by prevailing racist attitudes toward African-Americans, the dominant schools of sociology never questioned assumptions of inferiority or examined the impact of poverty, social stigma, or the legacy of slavery on the community. “White science and white supremacy walked hand in hand, justifying racial atrocity,” said Morris.

Du Bois’ methodology stood in stark contrast to this. Embedding himself in the communities he studied and taking the time to listen and collect significant data, he uncovered a spectrum of factors contributing to community ills such as poverty and crime. None of these included the alleged inferiority of African-Americans. In brief, by doing the work his white colleagues weren’t, Du Bois “discovered that accepted sociological knowledge was based in bias,” said Morris, “uncritical in the lack of weighing the evidence, uncritical from the distinct bias of the minds of so many writers.”

“Du Bois was the first sociologist to articulate the agency of the oppressed.”

Aldon D. Morris

With the evidence in hand, Du Bois called out the men who should have been his contemporaries, such as Cornell University sociologist Walter Willcox. “His mission was clear,” explained Morris, “to interject science into sociology.” In Du Bois’ hands, Morris noted, sociology became “a masterful science, capable of generating social change.”

The work Du Bois did to modernize his field has never been properly acknowledged, said Morris. For example, he pioneered urban sociology in the 1920s, becoming the “first American sociologist to develop structural analysis of social inequality,” he said. In addition, “By highlighting racial dynamics and power dynamics, Du Bois’s theory of the self predated those of [Charles H.] Cooley and [George Herbert] Mead by three decades,” he said, naming two respected leaders of modern sociology.

Perhaps more important, Du Bois’ work liberated his discipline from its role as an enabler of racism. A lifelong supporter of those who fought for equality, Du Bois died on Aug. 27, 1963, literally on the eve of the March for Jobs and Freedom (the “I Have a Dream” march) on Washington. Even after his death, the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. paid homage to Du Bois and drew on his findings, as have many Civil Rights leaders since.

“Du Bois was the first sociologist to articulate the agency of the oppressed,” said Morris. He said Du Bois established truth as a standard, elevating sociology to an “emancipatory social science” and by his example encouraged a more open and inclusive academia, for the good of all.