Gore Vidal debates William F. Buckley Jr.

Photos by Kris Snibbe/Harvard Staff Photographer

The life and legacy of Gore Vidal

Literary legend’s papers archived at Houghton Library

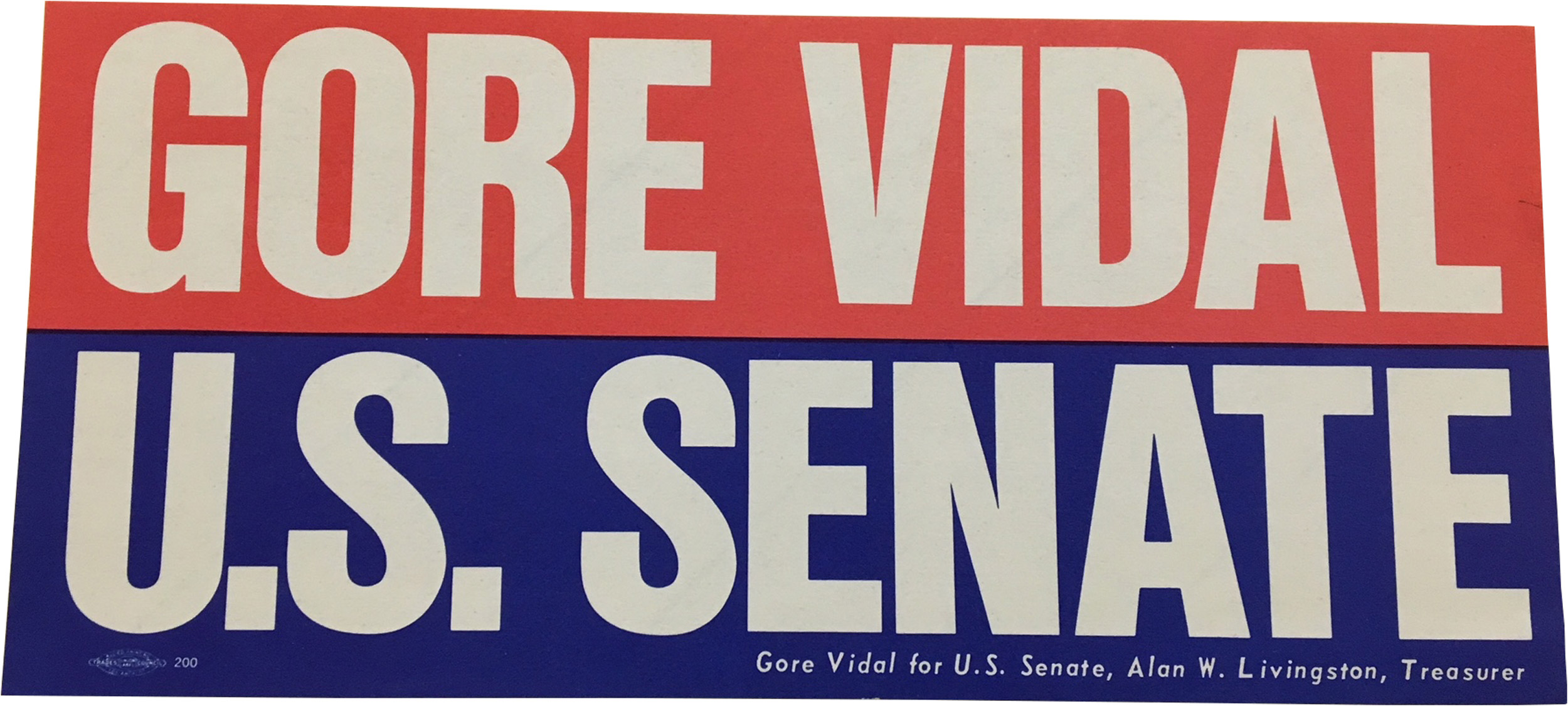

Gore Vidal was driven, brilliant, irascible, irreverent. He was a public intellectual, author, political candidate, autodidact, essayist, playwright, and provocateur.

He was also generous to Harvard.

Several years ago, Vidal left his papers and library to the University. Now the fruits of that gift, combined with an earlier gift of a portion of his papers in 2001, have been meticulously cataloged and archived at Houghton Library. The expanded collection captures the varied accomplishments of Vidal, who died in 2012, and traces the arc of his personal and professional life.

Spanning his boyhood to his final years, the roughly 500 shelf feet of material includes correspondence, drafts of his books and plays, photographs, videotapes, fan mail, and material related to his famously fiery exchanges with conservative author and commentator William F. Buckley Jr.

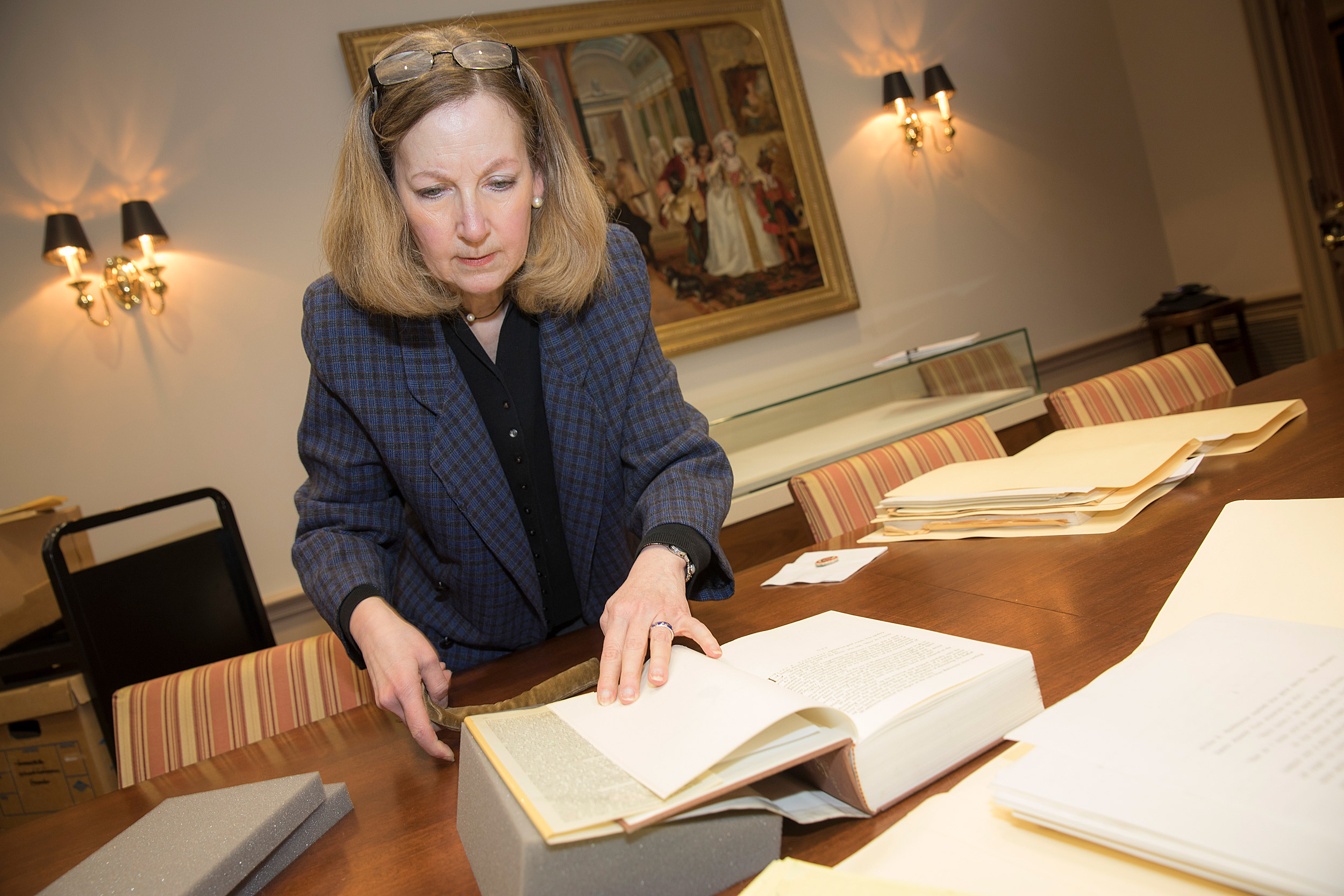

“He was involved in so many cultural issues of 20th-century America and contributed such an important voice, and his papers capture that,” said Leslie Morris, Houghton’s first Gore Vidal Curator of Modern Books & Manuscripts, who worked with the author through the years to fulfill his desire to bring the archive to Harvard. “From a historical and a cultural point of view, it’s an incredibly interesting and important collection that will continue to support research, teaching, and creativity at Harvard.”

In addition to the newly named curatorial position, Vidal’s gift also supports the Gore Vidal Professor of the Practice of Creative Writing. Author and essayist Teju Cole holds the position that began this academic year.

“It is very gratifying to see Leslie Morris become the first Gore Vidal Curator of Modern Books and Manuscripts, as her work on the collection and the relationship she fostered with Vidal and then his estate over the past two decades led to this transformative gift to the University,” said Thomas Hyry, Florence Fearrington Librarian of Houghton Library and director of arts and special collections of the Harvard College Library.

Collecting the past

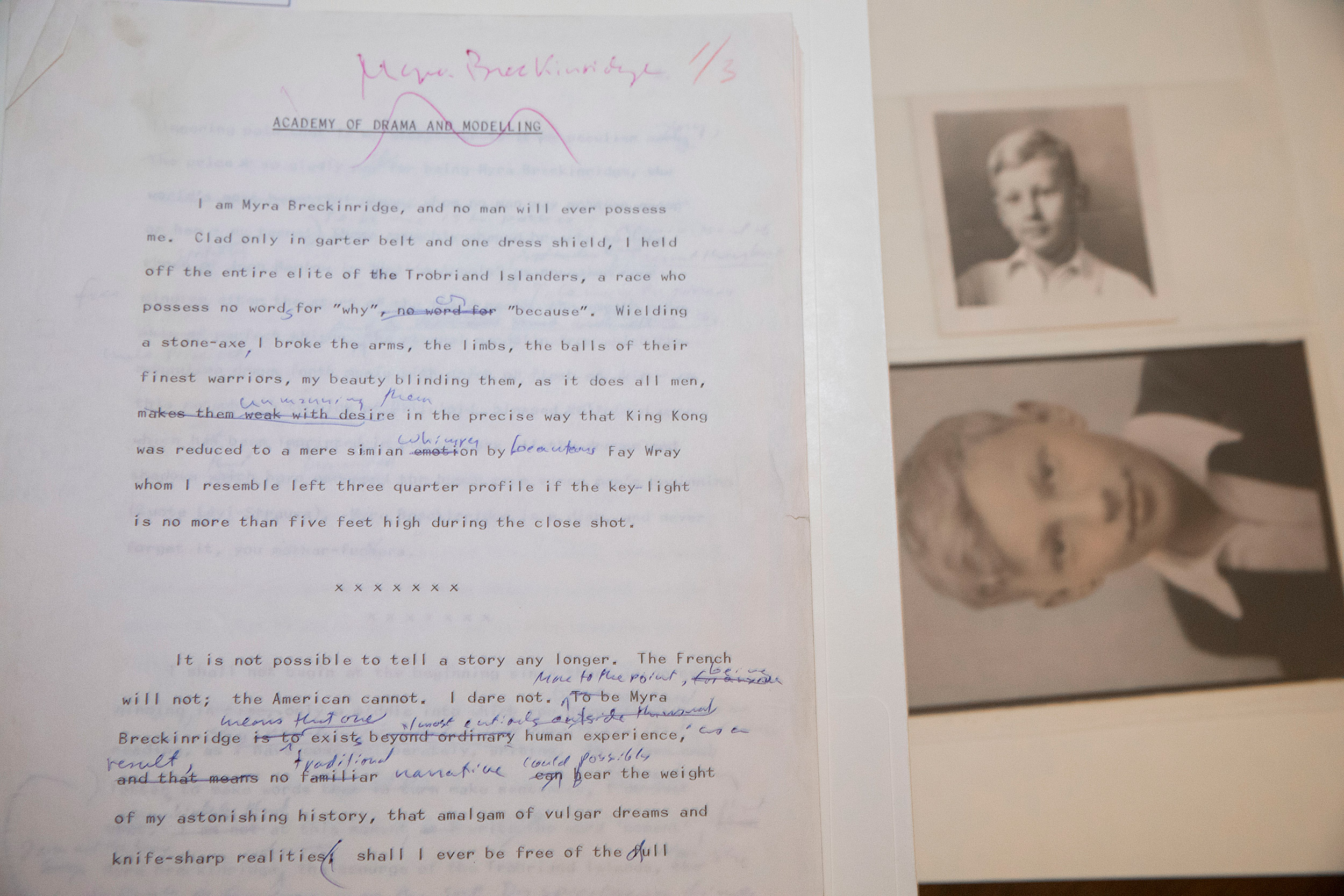

One afternoon last summer, in a room on Houghton’s second floor, Morris gathered a sampling from the papers, among them a selection of Vidal’s early manuscripts. In the corner of one handwritten page, yellowed with time, the author had scrawled the date, March 25, 1967. A few inches down begins the first chapter of his groundbreaking satirical novel about sexual norms.

“I am Myra Breckinridge,” Vidal’s swooping script reads, “and no man will ever possess me.”

Nearby lay an early draft of his 1946 debut novel “Williwaw,” written while Vidal was a maritime warrant officer with the Army. On the title page of the black-and-white notebook, Vidal underlined “40,000 words” for chapters 1 through 4, begun, according to his note, in “January 1945 on Cucumber Island in the Chesapeake Bay aboard the F.S. B5.”

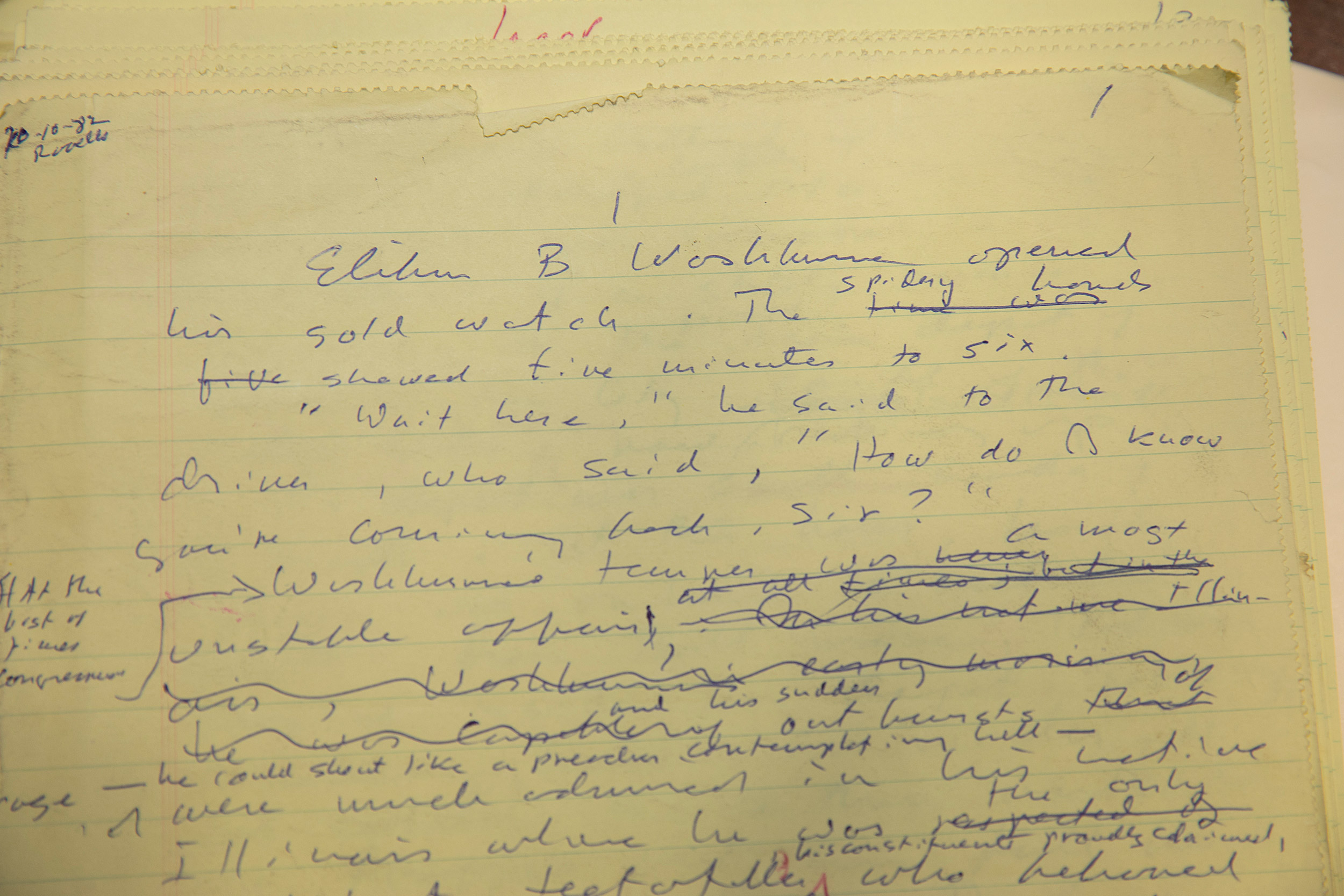

Morris called the handwritten texts “typical of the manuscripts in the collection. Throughout his life, Vidal’s first draft was always longhand.” The pages offer viewers a window into the author’s self-editing zeal. Sections of an early version of his most popular novel, “Lincoln,” about the country’s 16th president, are written on yellow-lined legal paper and covered with marginal notes, inserted words, and deletions in red or blue ink. “A cold winter day” becomes “an icy winter day.” “Shone” is replaced with “ablaze.” Later typewritten versions of the same manuscript include more revisions, revealing how Vidal tinkered with his words throughout the writing process.

“Throughout his life, Vidal’s first draft was always longhand.”

Leslie Morris

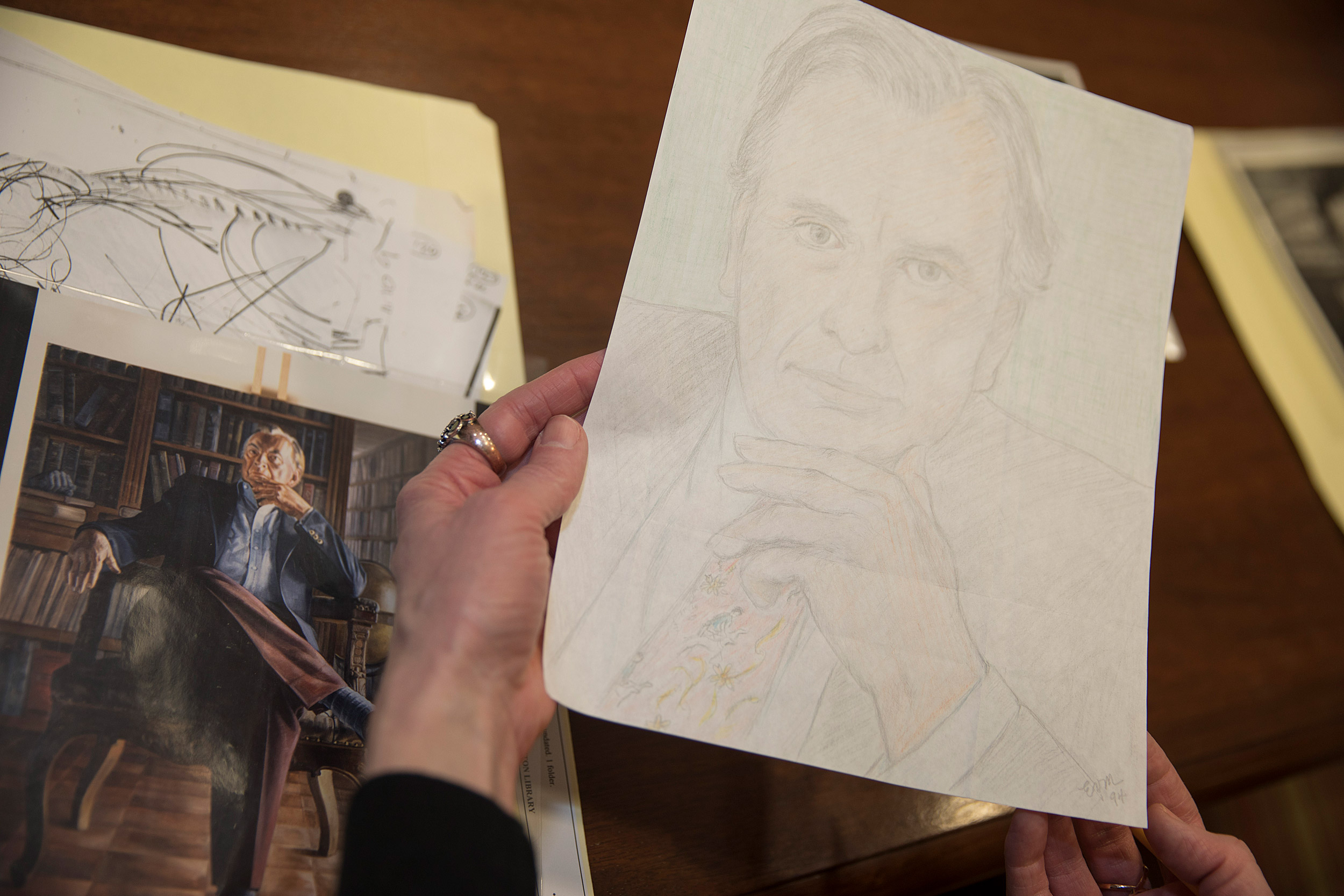

The collection includes early drafts of “Lincoln” and “Myra Breckinridge,” fan drawings, and photos of Vidal through the years. Here he’s pictured with Anais Nin.

Yet, his manuscripts, while popular, are not the most requested works in the collection. According to Morris, the literary entry attracting the greatest attention is Vidal’s screenplay for the erotic historical drama “Caligula.”

Other items in the archive point to Vidal’s friendships and feuds, including documents related to a libel lawsuit filed in 1975. Vidal sued novelist Truman Capote and the magazine “Playgirl” for an interview in which Capote claimed Vidal had been thrown out of the White House years earlier by Robert F. Kennedy. The case was settled in 1983 when Capote agreed to apologize to Vidal in writing.

Photos in the archive capture Vidal in his youth and later, alone and with friends. A black-and-white Polaroid from 1955 shows actor Paul Newman in a white T-shirt. In a photo dated 1956, Vidal is chatting with Newman’s wife, Joanne Woodward. The couple were well-known members of Vidal’s inner circle.

Vidal’s long ties to Harvard

Much of Vidal’s official archive arrived at Harvard years ago. The author initially deposited his papers at the Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research in the 1960s. Near the turn of the millennium, James Walsh, retired keeper of rare books at Houghton, visited Vidal’s cliffside villa in Ravello, Italy. While sipping drinks on the terrace overlooking the Amalfi Coast and listening to Vidal express concern about the handling of his papers, Walsh told the author he was certain Harvard would be happy to house the collection. Vidal agreed. Wisconsin released them, and the papers arrived in Cambridge in 2002.

“We promised that we would immediately catalog what he gave us, and that took us four years. It was a major investment of time on our part, but it was a very important gift, and a major research resource for us, so we were happy to make it a priority,” said Morris.

Vidal’s interest in Harvard, while not obvious, was longstanding. Some speculate it dates to his initial desire to matriculate at the College. In an interview with “Inside Higher Ed” in 2007, Vidal said he had been planning to attend until his military service interfered. When he mustered out of the Army in 1946, he thought that another four-year commitment, this time to Harvard where professors would tell him how to write, seemed, he told the publication, “too great a risk.” (His book “Williwaw” was already being published.)

In the late ’40s Vidal visited campus to lecture, addressing many of his former Phillips Exeter classmates in the crowd. He continued to lecture at Harvard through the years and even played the part of a Harvard professor in the 1994 film “With Honors.” During a campus visit in 2007 to check on his archive, library staff hosted him for lunch at the Faculty Club, where he was “incredibly charming and told great stories,” recalled Morris. “It was just a very, very pleasant occasion.”

Little did Morris know she would one day visit his home. Morris and assistant Heather Cole flew to California to survey the material in Vidal’s house in the Hollywood Hills. It was warm and welcoming, she said, filled with fine art and antiques alongside quirky memorabilia, such as casts of Abraham Lincoln’s hands honoring the publication of “Lincoln.” His bedroom was “beautifully decorated,” said Morris, with an “immense bed.” Its walls were covered with framed magazine covers of the author’s face, family photos, as well as a document commemorating his appointment by President John Kennedy to a White House cultural commission.

“His home was just lovely, with a lot of personality to it,” said Morris. “You could imagine him giving fabulous parties.”

Houghton Library will host a celebration in honor of the Gore Vidal bequest at Loeb House on Wednesday (Nov. 14) at 5.30 p.m., highlighted by “Gore Vidal in His Time,” a talk by Jay Parini, author of “Empire of Self: A Life of Gore Vidal.” A reception and pop-up exhibition at Houghton Library from Vidal’s papers will follow.

To RSVP for the event, click here.