The golden death mask of Tutankhamun.

Photos by Harry Burton; Copyright The Griffith Institute, Oxford University.

How Tut became Tut

Scholar explains role of photography in raising legend from the tomb

High tech has made ours an era of ubiquitous images — they flash on our phones, computer screens, and TVs, transmitted from around the world with the tap of a finger or the press of a button.

But in the early 20th century, the newspaper was the visual information superhighway, and the pictures displayed in London papers in January 1923 exposed the world to long-unseen wonders.

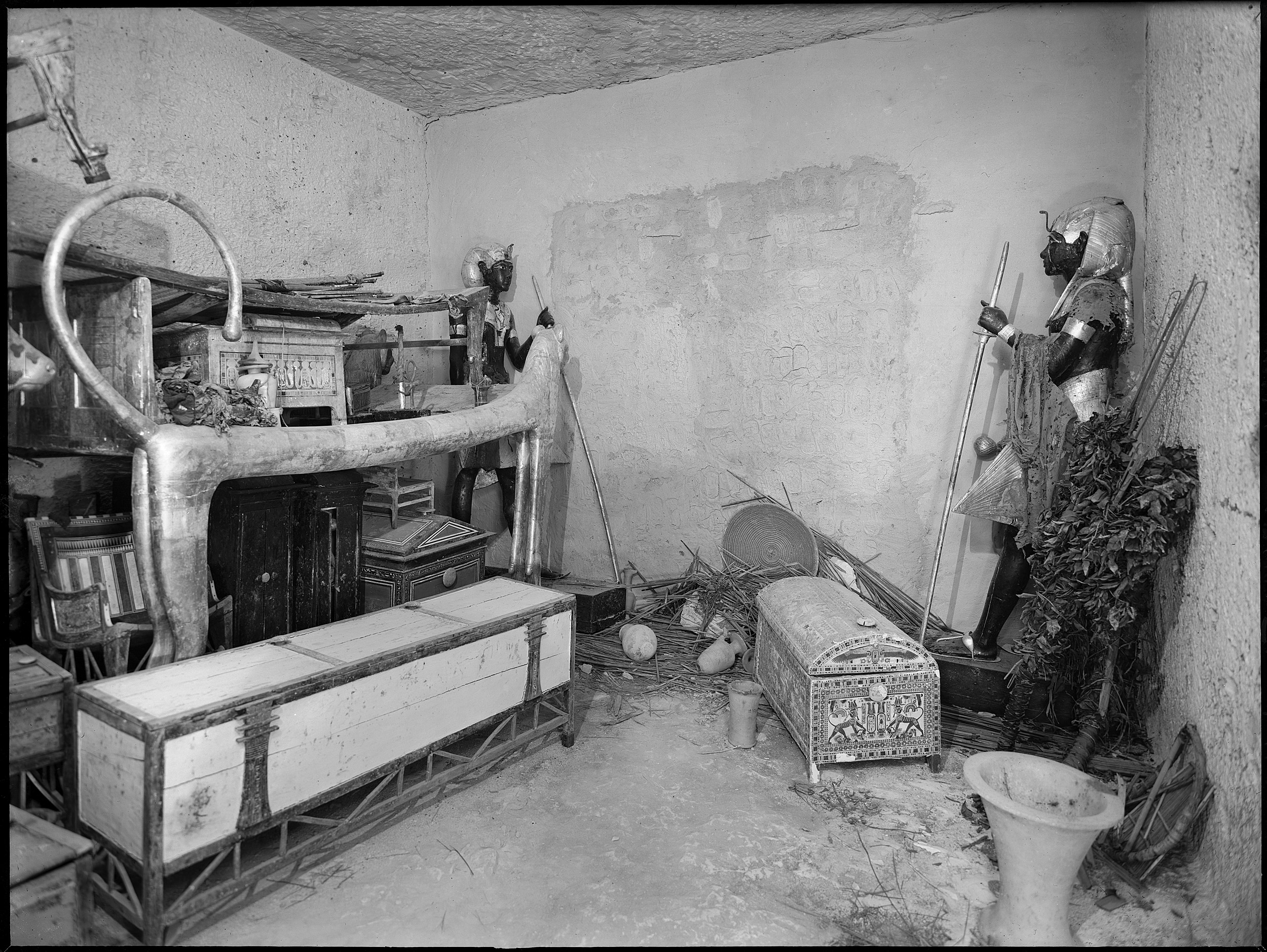

A few months earlier, when Howard Carter first peered into the dark antechamber of the millennia-old tomb of the Egyptian Pharaoh Tutankhamun, his colleagues eagerly asked the English archaeologist if he could see anything. Dazzled by the sight, Carter stammered back, “Yes, wonderful things.”

Images of some of those wonderful things appeared in print thanks to English photographer Harry Burton, who was working in Egypt on excavations for New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art.

By loaning to the dig the services of one of the best field photographers of the era, museum officials hoped to be rewarded with finds from the tomb, according to Christina Riggs, a professor of the history of art and archaeology at the University of East Anglia and author of the forthcoming “Photographing Tutankhamun: Archaeology, Ancient Egypt, and the Archive.”

In a recent talk at the Geological Lecture Hall, Riggs explored connections among archaeology, photography, memory, identity, and scholarship. The lecture was presented by the Harvard Semitic Museum with support from the Marcella Tilles Memorial Fund.

Most archaeologists think that “photographs are fact, and that their main and only interest lies in what they show,” Riggs told the crowd. “What interests me however, is what photographs do, and one of the things that photographs did for the discovery of Tutankhamun’s tomb was create that phenomenon that we now know as King Tut.”

Riggs explained that newspapers quickly adopted the nickname “to describe this long-lost, little-known pharaoh with so many symbols in his name.” Burton’s evocative photos turned the tomb “into a triumph for British and American archaeology,” she added.

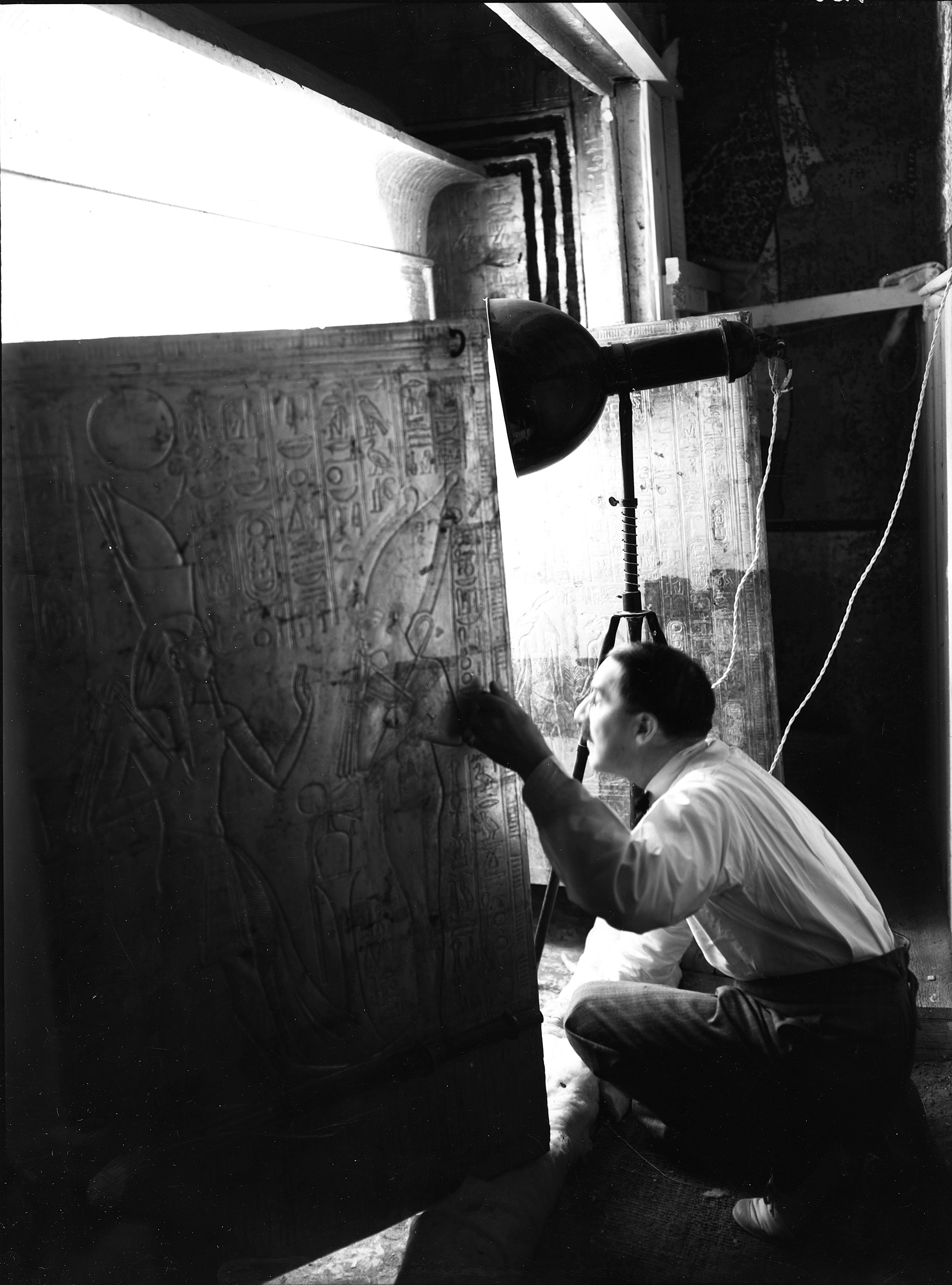

Carter peers in Tutankhamun’s burial shrine and examines his coffin in 1924.

Christina Riggs, author of “Photographing Tutankhamun: Archaeology, Ancient Egypt, and the Archive,” at the Harvard Semitic Museum.

Photo by Olivia Falcigno

The tomb’s pristine condition was a key factor in capturing the public imagination, said Riggs, as were its many splendors. But the discovery, she added, “also came at a crucial moment in time.”

More like this

Many felt that the tomb of King Tut, whose reign dates to the 14th century B.C., represented some of the first good news to emerge from Egypt in generations. The country had long struggled to free itself from control by the Ottoman and British empires, and the boy king, part of a long line of pharaohs who had ruled for 3,000 years, became an important symbol of Egyptian self-government. Egyptian writers took up the topic; teachers taught Tut in schools.

Helping fuel interest were Burton’s images of Tut’s golden death mask “in just about every different angle,” said Riggs. The photographs “arguably helped make [the mask] iconic. Burton helped create and perpetuate these interpretations.”

A further inspection of the camera work, said Riggs, reveals much about the realities of colonialism. Photos by Burton that depicted Carter working alone in the tomb were often staged, she said, and failed to capture the scope of the effort. In particular, the important contributions of four Egyptian workers who helped Burton carry equipment, set up shoots, mix chemicals, and develop negatives went largely unnoticed by the wider world. These workers occasionally appear in pictures showing Burton at work or posing with his camera, but they are uncredited, unnamed. The grown men were simply referred to as the “camera boys,” said Riggs, a label that highlighted “what assumptions and attitudes lay at the core of colonial-era archaeology.”

Yet without their help, Burton may not have achieved such stunning results. The assignment required that he capture images of objects before they were moved, after they had been cleaned, and in the intervening stages. Burton’s technique, including his choice to shoot the cleaned objects in front of a fabric screen and his use of glass-plate negatives, enabled him to eliminate shadows and capture the artifacts in the sharpest detail.

By 1933, the dig was over, and interest from newspapers had begun to wane. “Tutankhamun was no longer the top story,” said Riggs. In the end, the Metropolitan Museum received no artifacts from the dig despite Burton’s photographs having been the “star attractions” in the press. Still, as agreed, the institution was given a set of his images.

Today, copies of Burton’s archive, a record of more than 3,000 negatives and prints, are housed at the Metropolitan Museum and at the Griffith Institute at the University of Oxford, where they remain important sources of scholarship, exhibitions, and public fascination.

That enduring legacy might have surprised Burton. The self-critical, self-effacing photographer didn’t consider himself an artist or a scientist, as many of those working on the dig saw themselves, said Riggs. He was just a man from a modest background, she said, and “the guy with the camera.”