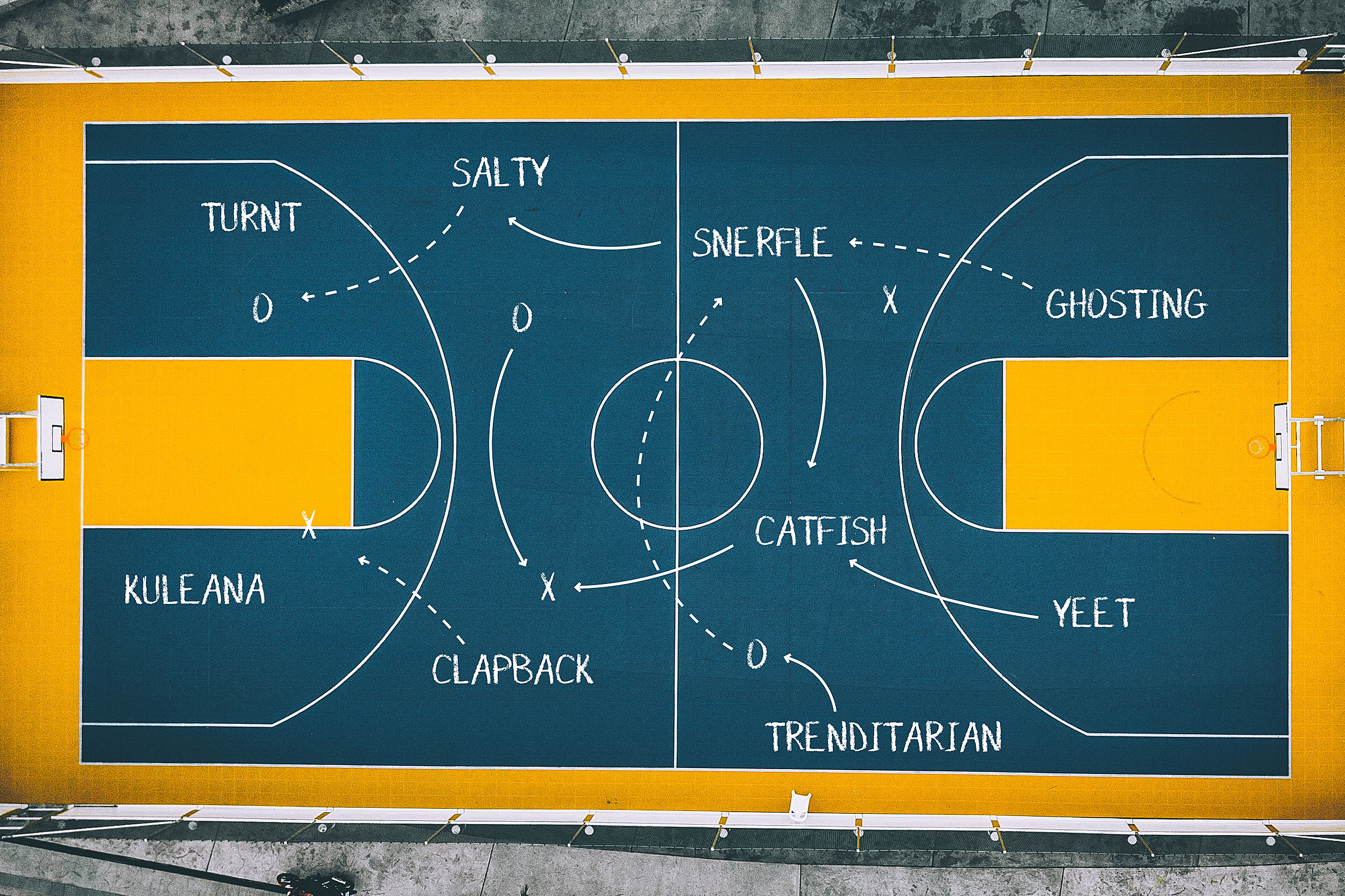

Illustration by Daniel Hassett-Salley/Harvard Staff

What’s in a word? The future history of English

Harvard course holds its own March Madness–style tournament for newly minted terms

Imagine the sounds of March Madness — fans screaming, basketballs bouncing, sneakers squeaking, the endless swoosh of nets — replaced with the vowels and consonants of words you’ve never heard of, and you’ll have a sense of what Word Madness is all about.

At Harvard, a history of English course is hosting its own March Madness–style tournament, substituting powerhouse basketball institutions with newly coined words that are making a splash in the English lexicon.

As part of Professor Daniel Donoghue’s general education course “The History and Structure of the English Language,” students submitted more than 100 words new to English usage, which were then organized into a championship-style bracket modeled on the NCAA basketball tournament. The bracket includes 64 words — such as “bae” (short for baby), “clapback” (a retort), “salty” (irritated), and “turnt” (overly excited) — that students are now voting on until a champion emerges in early April.

“It’s really fun seeing all these ‘new words’ get pitted against each other,” said College senior Rachel Chiu. “It’s funny seeing who comes up with what, what is considered ‘new,’ and seeing what definitions people come up with for words that we use in a very casual setting. It’s like seeing Urban Dictionary come to life.”

Donoghue, the John P. Marquand Professor of English, said he got the idea for the tournament from a similar exercise English Professor Andrew Warren did using poems a few years ago. While acknowledging the quirky fun, Donoghue hopes the project shows students how language evolves over time.

“Any living language changes,” he said. “One area where we can see obvious change and growth is in the lexicon — new words, new terms being introduced, or old words being put to new uses.”

“There’s just something comical about seeing a group of very smart linguistics students argue over the definition of something as colloquial as ‘lit.’ It’s very Harvard.”

Rachel Chiu

Examples of this are new words like “fleek” (meaning flawless), which was first recorded in 2014, or existing words, like “woke” (enlightened to social justice issues), that are now being used in new ways. While neither of those words made the Word Madness tournament, both have become broadly accepted, known, and used in larger society — sometimes to cringeworthy effect.

Many of the words in the tournament are colloquial terms made popular by millennials and Generation Z, partly because to qualify for the tournament they had to be words or usages Donoghue didn’t know, and partly because new words often reflect trends. Verbs such as “catfishing” (posing as another person or running a fake account) and “ghosting” (cutting off all contact, especially electronic) emerged primarily from online dating, while words like “lit” (extremely exciting) came from hip-hop and rap, which, according to the media research company Nielsen, recently surpassed rock as the most popular music genres.

More broadly, the project speaks to how new words and terms are created in many sectors of life, not just by younger generations and popular culture. In recent political news cycles, for example, the terms “alt-right” and “fake news” became mainstream, while internet- and smartphone-era terms such as “emailing,” “texting,” “force quit,” and “airplane mode” require no definitions for today’s technologically versed society.

“It’s fun to see new words pop up,” said Lacy Dawn McNeill ’21, an Extension School student taking the course.

In a class largely about the past, the project is an intriguing way to try to guess where the English language might be heading, McNeill and others said. Beyond that, it’s just plain fun and competitive.

“There’s just something comical about seeing a group of very smart linguistics students argue over the definition of something as colloquial as ‘lit,’” said Chiu. “It’s very Harvard.”

For McNeill, some of the best words submitted for the tournament are those that deliver certain effects. Words like “oof” (a response to someone’s misfortune, used mainly in texting) and “extra” (a person who’s trying too hard or goes over the top, as in “he’s so extra”) fit the bill. “I can’t really think of another word that accomplishes the same meaning,” she said.

Her word, “extra,” is coming off a first-round win over “veganity” (the state of being vegan) and a second-round win against “clapback.” Next, it is squaring off against “trenditarian” (someone whose diet follows current trends). The winner moves on to the Elite Eight round. She hopes “extra” goes through.

On the other side of the bracket is “yeet” (submitted twice in the tournament, both as a versatile exclamation used for emphasis, to convey excitement, or as a battle-cry, and, in this case, to mean “to discard an item at a high velocity”). Submitted by Clayton Henry, A.L.M. ’20, it won its opener against “embiggen” (to make bigger) and its second round matchup against the popular “bro-date.” Henry’s word narrowly avoided a potential matchup with one of Felix Bulwa’s favorite words, “dead” (incapacitated due to uncontrollable laughter), which was eliminated in the second round.

Bulwa ’22, who enjoys how word meanings shift over time, said students he knows use “dead” and others on the list, such as “shook” (extreme shock or surprise), daily.

He’s curious when the new meanings will be added to the dictionary.