Harvard art historians are analyzing the 70 objects discovered inside the statue “Prince Shōtoku at Age Two.”

Courtesy of Harvard Art Museums © President and Fellows of Harvard College

Studying Japan from ancient to modern

The University’s links with the island nation span more than a century

From ancient religious relics to present-day policy prescriptions to reverse demographic trends, researchers across the University are unraveling the mysteries of Japan.

Ancient secrets revealed

Some 80 years after a sculpture of the young Prince Shōtoku from Tokyo arrived in Boston, new research into the mysteries hidden deep inside this Buddhist icon will be revealed this spring at a new Harvard Art Museums exhibition.

“Prince Shōtoku at Age Two” is a revered sculpture dating back to 1292. Known as “Japan’s Sakyamuni,” or historical Buddha, it is the oldest datable statue of its type in the world and the most admired for its quality and beauty.

Made from Japanese cypress using an assembled woodblock method, “It’s spectacularly carved, the craftsmanship is exquisite,” said Rachel Saunders, Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Associate Curator of Asian Art at the Harvard Art Museums, who’s leading the research team.

A promised gift of Walter C. Sedgwick in memory of Ellery Sedgwick Sr. and Ellery Sedgwick Jr. to the Harvard Art Museums, the sculpture will be featured in “Prince Shōtoku: The Secrets Within” beginning May 25.

Though it is still ongoing, “This is the first time we felt that we could present that research in a way that’s meaningful,” said Saunders.

That work is part of the longstanding, deeply collaborative relationship between scholars and students from across the University and Japan. The ties, dating back to the 19th century, remain strong today, and include programs that offer student internships at Japanese firms and study abroad in Kyoto through Harvard Summer School, which marks its 10th anniversary this year.

On Sunday, Harvard President Larry Bacow will travel to Japan to meet with university presidents and other leaders, as well as Harvard alumni, to discuss the future of higher education following a six-day visit to China, where he spoke at Peking University.

“Prince Shōtoku” was first brought to the U.S. in the late 1930s by Ellery Sedgwick Sr., then-owner and publisher of The Atlantic Monthly, who had purchased it during a trip to Tokyo. Not long after, while on loan to the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, staff discovered and extracted 70 sacred objects, including tiny sculptures and bits of paper inscribed with prayers and poems, that had been stashed inside the statue’s hollow body and untouched for 700 years.

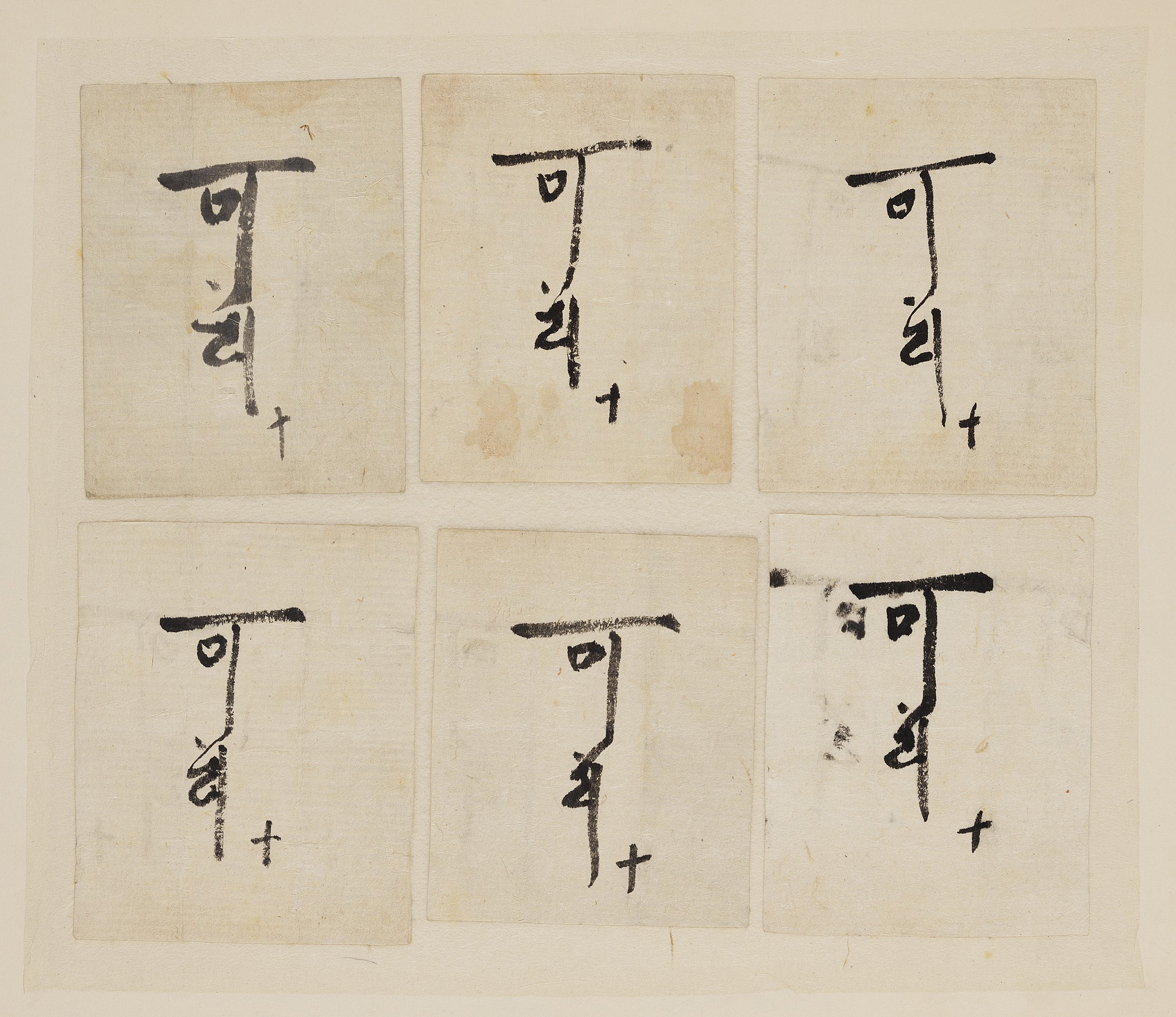

Glass and quartz relic grains and six Ordination Certificates (ninka) mounted on a board, two of the 70 artifacts found inside the statue “Prince Shōtoku at Age Two.”

Courtesy of Harvard Art Museums © President and Fellows of Harvard College

But World War II and the fractured relations between the U.S. and Japan that followed disrupted any further study of the statue until Harvard Professor John Rosenfield, a curator at the Fogg Museum, began his important work on the sculpture in the late 1960s.

In 2016, Saunders taught a graduate seminar with Melissa McCormick, a professor of Japanese art and culture at Harvard College, and Ryuichi Abe, Reischauer Institute Professor of Japanese Religions. For their final project, the students were asked to select an object from the sculpture’s cache, research and interpret it. The work proved difficult, but inspired the Harvard-based team of nearly two dozen faculty, students, conservators, and Buddhologists from Nagoya University in Japan who have assisted with transcription of the texts, to delve even deeper.

“It’s an extremely complicated object, not just the sculpture itself, but trying to understand what all the objects inside exactly are and what they mean together has been a very complex process, and so it’s really taken until now” to amass the necessary technical, institutional, and human resources in one place to study it properly, said Saunders.

With record keeping less detailed than it is today, no one knew where the objects had been positioned inside the sculpture before they were extricated in the 1930s. Such information is important, as some items have more salience than others, so where they were placed inside would have had meaning, she said.

“Some of the questions we had couldn’t be resolved by just looking at the sculpture from the outside in. We needed to look from the inside out, as well,” said Saunders.

So the sculpture was X-rayed and then brought to the Harvard University Center for Nanoscale Systems for a CT scan that took two days to complete, but delivered a treasure trove of visual data.

Most recently, Saunders and Angela Chang, a conservator and assistant director of the Straus Center for Conservation and Technical Studies, visited a number of temples and museums in Japan last summer to survey sculptures similar to “Prince Shōtoku” to compare and learn more from local curators about the different construction and preservation techniques used in the late 14th century, and also to share what the team had uncovered about the prince.

At the exhibit, visitors will be able to see all 70 of the objects reunited with the sculpture for the first time and take advantage of a new online resource that will offer greater detail about the transcription and conservation efforts the research team undertook.

“‘Shōtoku’ is very charismatic, and what we want to do in the exhibition is enable people to have a real encounter with him,” said Saunders. “He was created to do that. He was created to bring together ‘communities of empathy.’ He’s a center for people to gather around … he’s doing that here again at Harvard, though in a different context.”

Modern challenges addressed

Harvard’s interest in Japan extends from its ancient treasures to its modern challenges, including its low birth rate. Though the challenges in places with rapidly growing populations, such as many nations in sub-Saharan Africa, are well-known — famine, infectious disease, poverty — what is less understood are the causes and complications in countries where births are not keeping pace with deaths.

Mary Brinton, Reischauer Institute Professor of Sociology and director of the Edwin O. Reischauer Institute of Japanese Studies at Harvard, has been studying the factors at work in countries with historically low birth rates in parts of Europe and East Asia, especially Japan. She and her team first interviewed young adults in low-birth-rate countries in 2012 and 2013 about their prospects and plans for parenthood. They are currently doing follow-up interviews to learn whether interviewees have had children and if not, why. The findings of her study and others suggest that there’s a “strong correlation” between low birth rates and high levels of gender inequality, particularly in Japan.

Though Japan’s birth rate has been in decline for 30 years, a related cultural marker reached an ominous new peak in 2018: About 25 percent of women and more than 30 percent of men in their mid- to late 30s (a demographic often studied because it comes at the tail end of fertility) have never married. It’s a very high percentage for an industrialized country.

The reason can be traced to rigid gender expectations that leave Japanese women and men with few choices when it comes to career and family life, said Brinton. Fewer than 5 percent of children are born outside of marriage in Japan. And to marry, the vast majority of young Japanese men and women expect a man to have a stable job so that he can be the sole, or at least the primary, breadwinner in a family.

Gender inequality in wages, the very long work hours expected by employers, and the cultural expectation that women do nearly all of the housework and childcare mean that most full-time working women cut back their work hours or leave the labor force entirely when they have a child. If the husband is high-earning, having two or more children is possible, but only in this rare situation.

Highly educated, career-oriented women face a stark choice. They can forgo marriage and children in order to meet the long work-hour demands, or they can marry and have children, and accept that an egalitarian marriage is nearly impossible given men’s long work hours. The women interviewed told Brinton’s team that men arrive home from work at 9 p.m. on average, with many arriving later. Even where there is a desire to divide household and childcare duties more equitably, nearly all of the women said it was simply impractical to expect their spouse to clean the bathroom or make dinner after working a 12-hour day.

For lower-status, less-educated men and women, the picture is bleak for different reasons. Men who cannot land a stable job that will pay enough to support a wife and child generally remain single and childless, deemed undesirable in the marriage market. These men’s female peers who want to stay home and have a family and would otherwise be good matches also cannot start a family until they find a reliable male provider.

“It’s the rigidity of what men’s and women’s roles are supposed to be within the family and also in the workplace” that is driving Japan’s low birth rate, said Brinton.

Change won’t be easy. With a rapidly aging society (last fall, the Japanese government announced that for the first time, 20 percent of the population was 70 or older) and an ever-diminishing pool of young workers to keep the economy going, Japanese companies have been scrambling for solutions.

Many big firms are trying to change corporate culture and, for example, encourage men to take childcare leave. But so far, these efforts haven’t made much difference. It has been tough to uproot ingrained cultural norms about gender roles and worries over cutthroat business competition if work hours are shortened.

“If the Japanese government could convince companies to lower work hours, to look at productivity on the job in a different way than ‘face time,’ and to strongly encourage men to take at least some childcare leave, it would have positive ripple effects for the family, for gender equality, [and] for the fertility rate,” said Brinton.