A new study shows that older men who maintain healthier diets are 25 percent less likely to develop physical impairment with aging.

Pixabay

Healthy diet helps older men maintain physical function

Associated with 25 percent lower likelihood of developing age-related impairments

A person’s ability to maintain independence and physically care for themselves is an essential part of healthy aging. But few studies have examined how diet may allow some aging people to maintain physical function — everyday tasks such as bathing, getting dressed, carrying groceries, or walking up a flight of stairs — while others’ abilities diminish.

A new study by investigators from Harvard-affiliated Brigham and Women’s Hospital examines the role of a healthy diet and finds that this highly modifiable factor can have a large influence on maintaining physical function, lowering the likelihood of developing physical impairment by approximately 25 percent. The team’s findings are published in The Journal of Nutrition, Health and Aging.

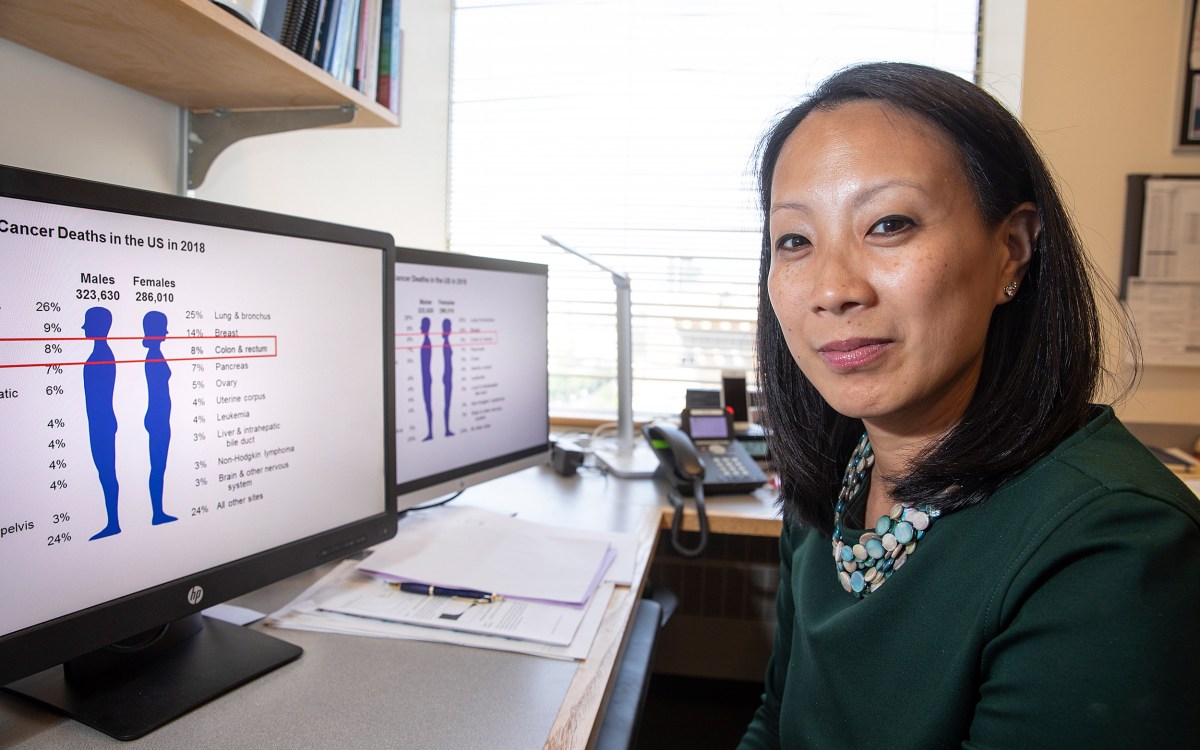

“Diet can have specific effects on our health and can also affect our well-being and physical independence as we get older,” said senior author Francine Grodstein of the Channing Division of Network Medicine at the Brigham Hospital. “What excites me about our findings is the notion that we have some influence over our physical independence as we get older. Even if people can’t completely change their diet, there are some relatively simple dietary changes people can make that may influence their ability to maintain physical function, such as eating more vegetables and nuts.”

Grodstein and her colleague Kaitlin Hagan, a former postdoctoral fellow at the Brigham, examined data from a total of 12,658 men from the Health Professionals Follow-Up Study, tracking them from 2008 to 2012. At the beginning of this period, all men were assessed for their ability to perform such activities as bathing/dressing themselves, walking one block, walking several blocks, walking more than one mile, bending/kneeling, climbing one flight of stairs, climbing several flights of stairs, lifting groceries, moderate activities, and vigorous activities. The men also filled out a food-frequency questionnaire with responses ranging from “never or less than once per month” to “six or more times per day.”

The team used criteria from the Alternate Healthy Eating Index-2010 to assess the quality of each of the men’s diets and assign an individual score. These criteria included six food categories for which higher intake was better (vegetables, fruit, whole grains, nuts and legumes, long-chain omega-3 fatty acids, and polyunsaturated fatty acids); one food category for which moderate intake was better (alcohol); and four categories for which lower intake was better (sugar-sweetened beverages and fruit juice, red and processed meats, trans fatty acids, and sodium).

Grodstein and Hagan found that higher diet scores (meaning better diet quality) were strongly associated with decreased odds of physical impairment, including a 25 percent lower likelihood of developing impaired physical function with aging. An overall healthy diet pattern was more strongly associated with better physical function than an individual component or food. But the team did see that greater intake of vegetables and nuts and lower intake of red or processed meats and sugar-sweetened beverages each modestly lowered risk of impairment.

The study’s results largely align with findings from similar studies of women in the Nurses’ Health Study. Like many studies of diet, the current study relies on self-reporting and answers from questionnaires, which has some flaws. However, since the study examines overall healthy eating, minor discrepancies are unlikely to have had a large impact on the findings. The team’s prospective design — following initially healthy adults who could perform physical activities as they aged — strengthened their study and minimized the likelihood of reverse causation bias (or changing one’s diet due to physical impairment).

This work was supported by grants UM1 CA167552, and T32 HL098048 from the National Institutes of Health. Grodstein received unrestricted research awards from the California Walnut Commission and Nestlé Waters LLC.