A colorful figure

Professor reckons with his family’s history in a study of his talented, if eccentric, relative’s art

Philip Deloria’s family had never taken his eccentric great-aunt Mary Sully’s art seriously. He remembered thinking, back when he was a kid, that her pencil drawings were “elaborate doodles,” judging them “cool, but weird.” Deloria first unpacked them with his mom in the 1970s, and though he carried three favorites with him as he moved along in his life, the full set of drawings were not given another look until two decades later.

That’s when the professor of history discovered Sully (given name Susan Deloria) was an artist of two worlds. On one side of her family she was descended from American portrait painter Thomas Sully (“The Passage of the Delaware” and Andrew Jackson’s portrait on the $20 bill) and on the other, members of the Dakota Sioux tribe.

In his new book, “Becoming Mary Sully: Toward an American Indian Abstract,” Deloria couples her personal story — a life battling anxiety and possibly synesthesia, as well as her complicated relationship with her sister, the anthropologist Ella Deloria — with an examination of her art, which defied categorization in the early 20th century. Core to her collection are 134 “personality prints,” three-panel pieces inspired, in many cases, by artists and celebrities including Babe Ruth, Gertrude Stein, and Amelia Earhart. Three of Sully’s works appear in “Hearts of Our People: Native Women Artists,” which recently opened at Minneapolis Institute of Art. Deloria talked to the Gazette about Sully’s modernist mind, his family’s past, and how he hopes to elevate his great-aunt’s work.

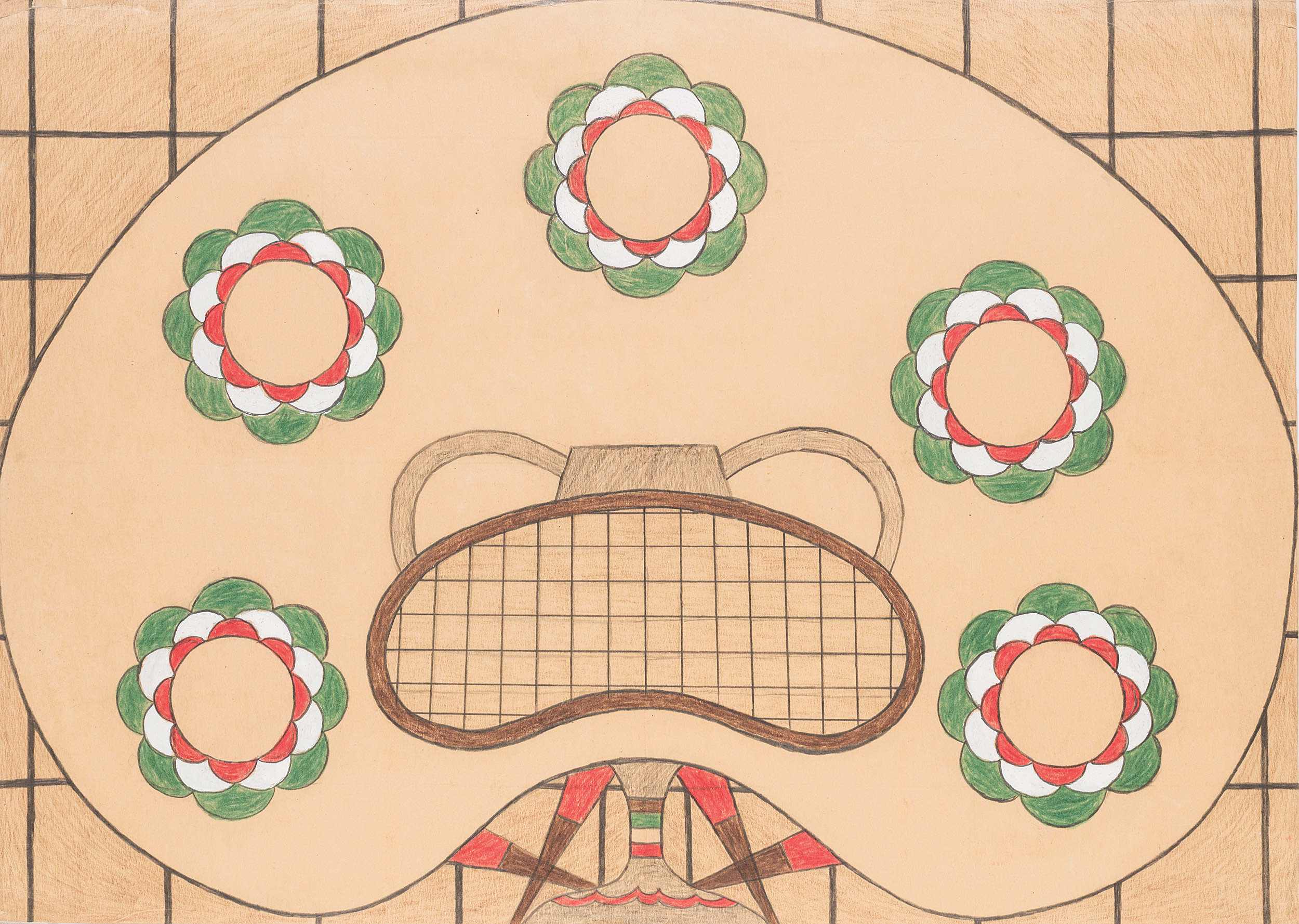

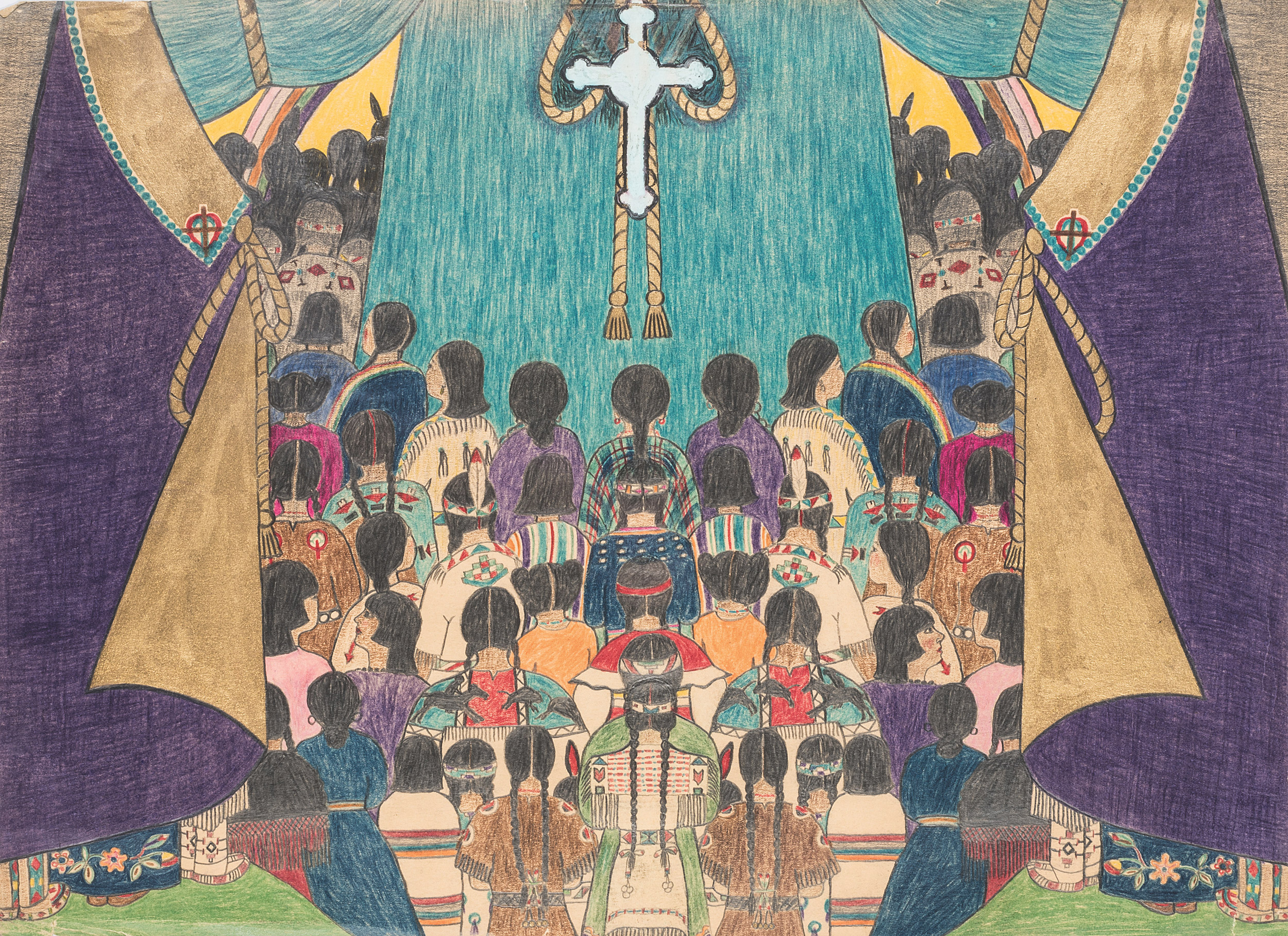

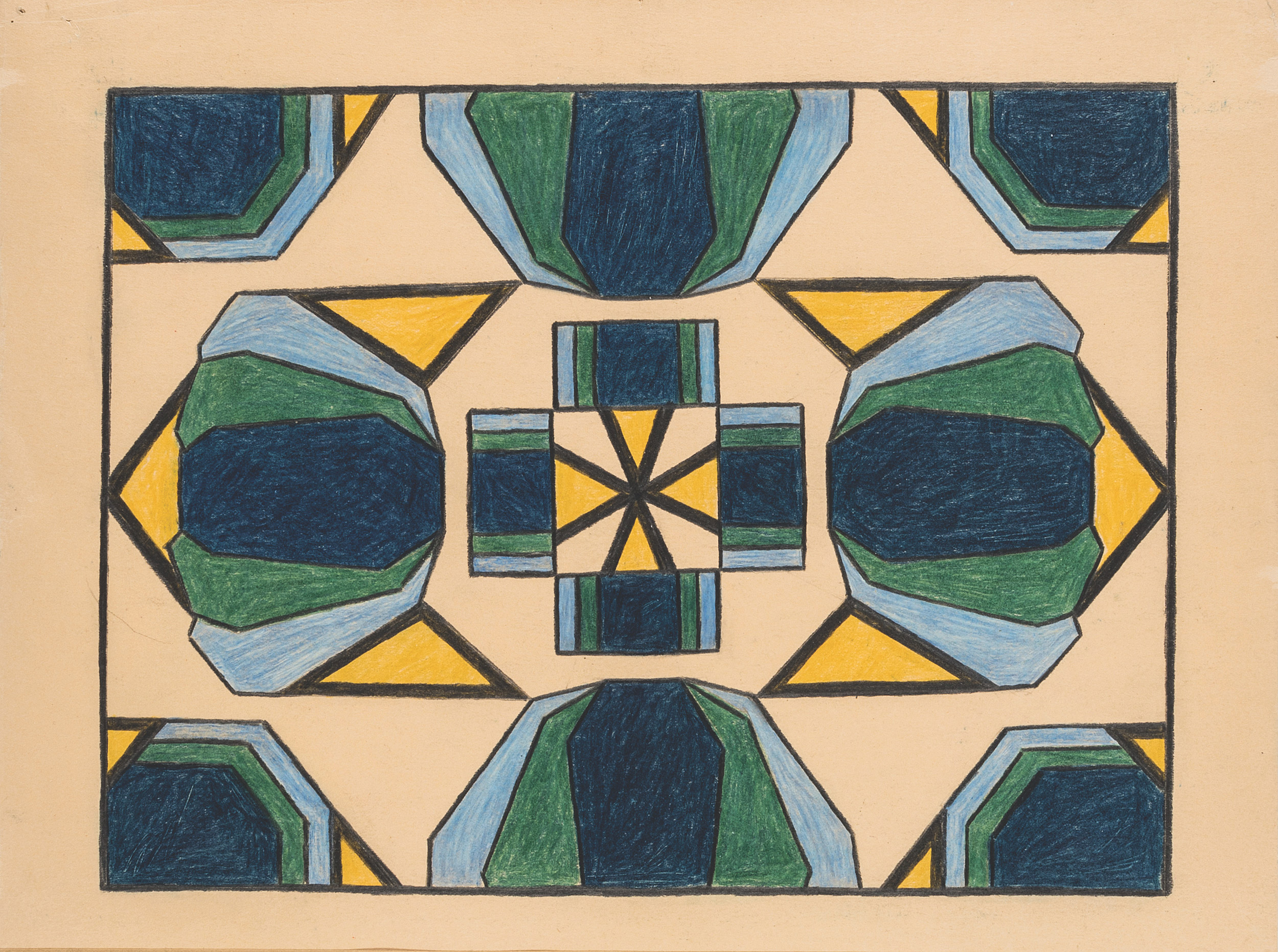

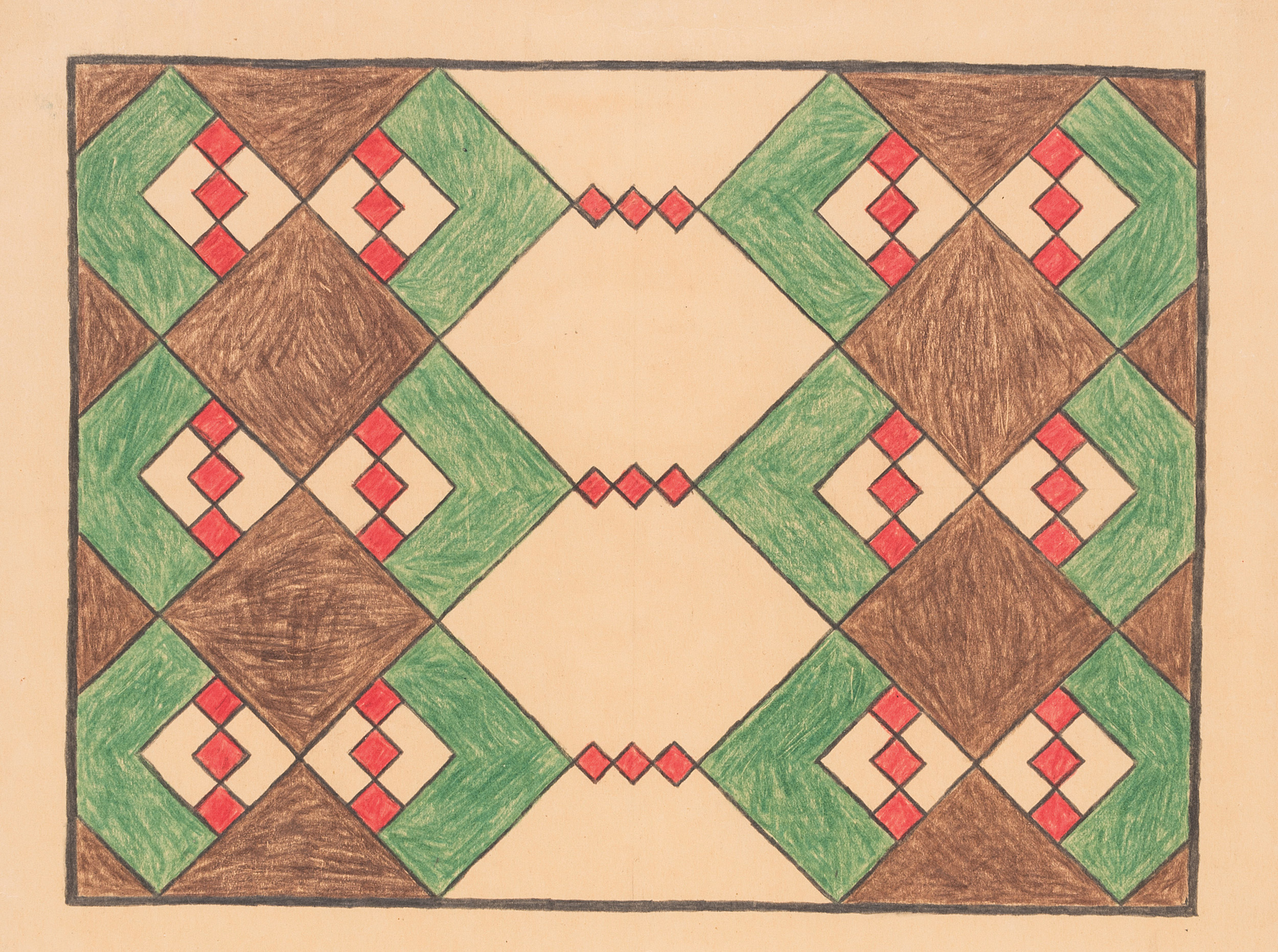

Two examples of Mary Sully’s three-panel pieces, “Three Stages of Indian History” [above] and the “personality print” for Cornelia Otis Skinner [top of story], an actor and playwright specializing in historical dramas about women. Sully’s triptychs often followed the same structure: the top panel evoking a famous personality, the middle panel a geometric motif of the same theme, and the third a nod to Native influences.

All images courtesy of Philip Deloria

Q&A

Philip Deloria

GAZETTE: How did you come to know your great-aunt’s work?

DELORIA: The first time we looked at the personality prints was in the ’70s. I remember my mom and I opening this box and being mystified by them and thinking, “Well, they are kind of cool … but a little weird.” And this is where the sense that these are just elaborate doodles kind of came from. We didn’t really take her seriously as an artist because no one really had taken her seriously as an artist, in the family or elsewhere. That was a beginning point. There were three I really liked that I carried around with me for a while.

GAZETTE: Which ones?

DELORIA: All three Indian ones: “Indian Church,” “Indian History,” and “Bishop Hare.” So I was reading and extracting her Indian-ness out of the collection from the beginning. And then in 2005‒06 after my dad passed, we pulled them out again and that’s when all of a sudden they took on a new set of meanings to me. In the ’70s they were mystifying, and we couldn’t make sense of how they worked; when we pulled them out in the 2000s and you could Google people, they took on deeper meaning much more rapidly. The images were referencing events in the lives of these individuals or widely understood elements of their character, albeit in quite abstract ways.

“This is truly modern art, modern design, with its cross-racial themes, its fascination with celebrity and popular culture. There were moments when I thought, ‘Andy Warhol. She was here first.’”

The top panels for Sully’s personality prints depicting dancer Fred Astaire and tennis star Helen Wills.

GAZETTE: Were you surprised at her interest in celebrity? You were drawn to the ones that were about Native American life, then you realize she was also into Babe Ruth.

DELORIA: Yes, there were a bunch of light-bulb moments. One was: Wait a minute. She doesn’t seem to care about Indian subjects as she “should.” She cares about film stars and baseball stars and people on the radio. There was a big light bulb around that — how does she come up with this archive of people she wants to represent? A second was that the more you know about the people, the deeper the image becomes. This is consistent. It was easy to think superficially about the image, but then when you started looking into who these people and personalities were, you started to understand new things about the triptychs. My prototypical example is Malcolm Campbell, a race car driver. There is a curious blue bird and some oddly shaped circles in the image, but you could never understand why until you understood Campbell, knew that he set speed records in a car named “The Bluebird,” and wore these circular goggles. Or Lawrence Tibbett, an opera singer. It took me a long time to figure his image out because it centers on an optical illusion that makes it look like a kind of bizarre humanoid trilobite. But as I dug into his background and discovered that he had a cottage in Temescal Canyon and would stand on the amphitheater stage and sing, suddenly I realized: “This is an abstract picture of a canyon!” The image took on new life and richness. The more I had those experiences, the more I became convinced that these works were important.

Shortly after we opened up the box, I did a paper at a Smithsonian conference on American and Native American art. I wasn’t quite sure what to do, so I shot some photos of the images and I did a 20-minute piece and said, “Aren’t these interesting?” and I thought, “Well, that’s that.” But people who were doing art history came up and said, “You should pursue this some more.” It turns out that I wasn’t the only one who thought they were interesting.

GAZETTE: So you had art experts telling you that, but you’re not an art historian. So how did you navigate not being an expert in this area in pursuing this book? Did you collaborate or did you do a lot of research?

DELORIA: I tried to do a lot of research to understand what art historians were thinking about modernism, what Native American art historians were thinking about in the period of the 1920s and ’30s. I would never claim to be an art historian, but, as an American studies person, the most influential person in my training was Jules Prown, a really key figure in material culture studies. He wrote two important essays in the ’70s that were explicitly and usefully methodological and transformative for me. His method was drawn from art history — super-close readings, subjectively engaged experiences — which he translated into material culture studies. So I reverse-engineered that set of methodological approaches back into art history and let it see where it would take me.

I also did a lot of consulting. It’s a very collaborative piece of scholarship. I was doing academic administration at the time I was developing the project so I had very little writing or research time. I would do it as a talk. I’d listen and speak to audiences and gather information and think some more, and then reiterate. It took me a little while to realize the extent to which it was a community project — that giving a lot of talks was a kind of method in and of itself. There were some people I just didn’t get their names. There’s a synesthesia argument in the book, for example, and there was a young man at the University of Nebraska, Lincoln, who came up after a talk and said, “I’m synesthetic, and this is exactly how I see the world. You should think about whether she had synesthesia.”

People would press me about how I was doing the readings. I did this talk in Taiwan, for example, and my colleagues asked, “Why do you think reading the three parts of the triptych from top to bottom is important? Maybe you should read from bottom to top.” So I had six to eight years of really rich, robust conversations with people. And I had five or six great friends read the final drafts — some are art people; some are experts in modernism; some in Native arts — so it’s a very collective book.

Middle panels, Astaire and Wills.

GAZETTE: So let’s move to the personal because this is your family’s story, and Mary is so heartbreaking in her eccentricities. She wrote that she felt she had psychological issues. How did you come away thinking about her?

DELORIA: She could be a hard person. It’s pretty clear from just the family aura around her. My dad had not much sympathy for her sometimes. My mom thought her quite odd. She had an interesting encounter with mental health and mental hygiene professionals in the 1920s, right before she began the project. I wanted to maintain that sense people in my family had of her, but the art is so stunning that there has also to be a redemptive moment. You think of the discipline needed to sit and draw for over a decade: 134 images times three. It’s a lot of drawing. There’s a tight focus, maybe an obsessiveness. There is indeed something about her own mental health that sits in relation to her as an artist. You can find that in lots of artists’ biographies, of course. Artists are not like the rest of us! So I wanted to think about it in somewhat familial terms but also offer conceptual road maps about how the art works and how we might make sense of it. It’s interpretive and analytical when it comes to the images.

I must have been in the same space as her when I was a baby, but I didn’t have real memories of her the way I did of her sister, Ella. I didn’t have a close personal investment. So I was able to keep a certain distance, but it’s a box of art that is also a box of stories. In some ways pulling back out the Alfred Sully story might have been among the most wrenching things. This is a family that has a huge, deep history of making significant family contributions for Native American people, but it’s also a history that has a colonizing side. And in that genealogy, here’s Alfred Sully, who was not only a painter and the son of a painter, but also an Indian-killing military officer. There is no other way to talk about him.

Promotional photographs of artist Mary Sully and her sister, anthropologist Ella Deloria. “These two sisters were a bit codependent,” Philip Deloria said, “but they were also co-intellectuals operating in these overlapping realms.”

There was an incredible moment of excitement when we pulled together the three paintings he had sent home to his father, Thomas Sully, and were able to reunite them on a single page. It was an amazing reconstruction, but you also have to recognize who he was and what he did. In light of the rest of the family story, that genealogy sits in such tension. Surfacing it and making Sully central to the occasion and thinking about the way she pragmatically embraced his name — that was a bit of a tough moment.

GAZETTE: Your ideas about her art evolve, from first thinking she’s a doodler, to appreciating her real contributions to early 20th-century modern Native American art. Can you talk about this evolution?

DELORIA: I had a whole series of interpretive explosions in my head the whole way through, both in terms of the individual images and how the whole collection fit together and fit into the moment. I had always been aware of a standard historical trajectory of Native arts, which is often narrated as beginning in the 1920s and ’30s. I really enjoyed engaging that tradition and appreciating the quality of these Native arts, but also understanding the constraints placed upon it. The book has to account for the ways that her work was so radically outside that Native arts tradition.

Bottom panels, Astaire and Wills.

Another important context centered on what was happening in the American art world when she was producing the personality prints, and how radically different her work was from that art as well. She was not of the moment, although she could have been — but her vision really seems to have emerged out of the aesthetics of the teens and the ’20s. She’s enacting a vision of modernist art that is in some ways looking back over a collective Americanist shoulder, and she’s elaborating certain themes that were a bit of the past moment, but she’s also integrating these things in ways that are forward-looking: This is truly modern art, modern design, with its cross-racial themes, its fascination with celebrity and popular culture. There were moments when I thought, “Andy Warhol. She was here first.”

As I worked on the book, I learned to read more and more deeply, and started to see the aesthetic cross from image to image. I found myself arguing that the bottom panels really reflected a complicated sense of indigeneity. Here’s a beadwork pattern. Oh, and look, these Venetian blind patterns are drawn from older Great Plains women’s arts traditions — mostly. It’s not a traditional traditionalism, and it’s not an unfettered cosmopolitanism.

It’s an interesting space, and I went from thinking, “She’s my oddball great-aunt” to thinking, “She’s really a genius.” As complicated a person as she was, I found myself respecting and appreciating her more and more. It had always seemed to everybody that Ella was taking care of her and by the end, I came to realize that this was not really the case. These two sisters were a bit codependent, but they were also co-intellectuals operating in these overlapping realms. These realizations were so fun and so satisfying. I suspect that I’ll never have a project this good again.

“I went from thinking, ‘She’s my oddball great-aunt’ to thinking, ‘She’s really a genius.’”

GAZETTE: So now the challenge seems to be: How do you get her work out there?

DELORIA: My naïve sense when I was first talking to the Smithsonian was: “We will have an exhibit. We’ll have a catalog and recruit the smartest art historians.” And they said, “A single-person show — your nutty great-aunt’s box from the basement — is a hard pitch. You have to force us to engage with this. You have to write a book that forces us to say, ‘This art is important and worthy.’”

“The Hearts of Our People” exhibition in Minneapolis is a great start. It’s a fantastic and beautiful show, brilliantly curated by Jill Ahlberg Yohe and Teri Greeves, and it features amazing works by Native women across time, place, media. I could not be more honored to have Mary Sully’s work included there. Indeed, when I attended the opening and saw the pieces on the wall at a major institution in a pathbreaking show, it was quite emotional. My wife and I were a bit teary-eyed, especially as we stood to the side and watched viewers engage the art. I couldn’t help but think of my great-aunt’s last years. She had mostly given up making art. The personality prints had been displayed maybe three times, at Indian schools, and that was it. The pieces were stuffed in a gray box, and I have to think that she probably wondered what would become of them, and that her assessment was probably not optimistic. And now, here it is, reanimated, able to speak to viewers in ways that she could only dream about back in the 1930s. I am humbled to think that I could play a small role in bringing that about.

And now there’s more work to be done. The pieces need conservation work. Perhaps there’s a print show in the future, and maybe more interest from other museums and curators. I hope so. I’d like to think that there’s a kind of synchronicity in the universe that, at that very moment that this book was in production and the work for “Hearts of Our People” was wrapping up, the Guggenheim Museum’s Hilma af Klint show was wowing New York City and the art world. The two artists aren’t the same, but they share a lot of common elements: women artists with claims on aesthetic developments of modernism; archives that had been hidden for decades only to reemerge; beautiful and stunning uses of geometry and color. So I’m hoping that there’s also a future for Mary Sully’s work. As I said, it is the best project I’m likely to have in my career, and I think it’s far from over.