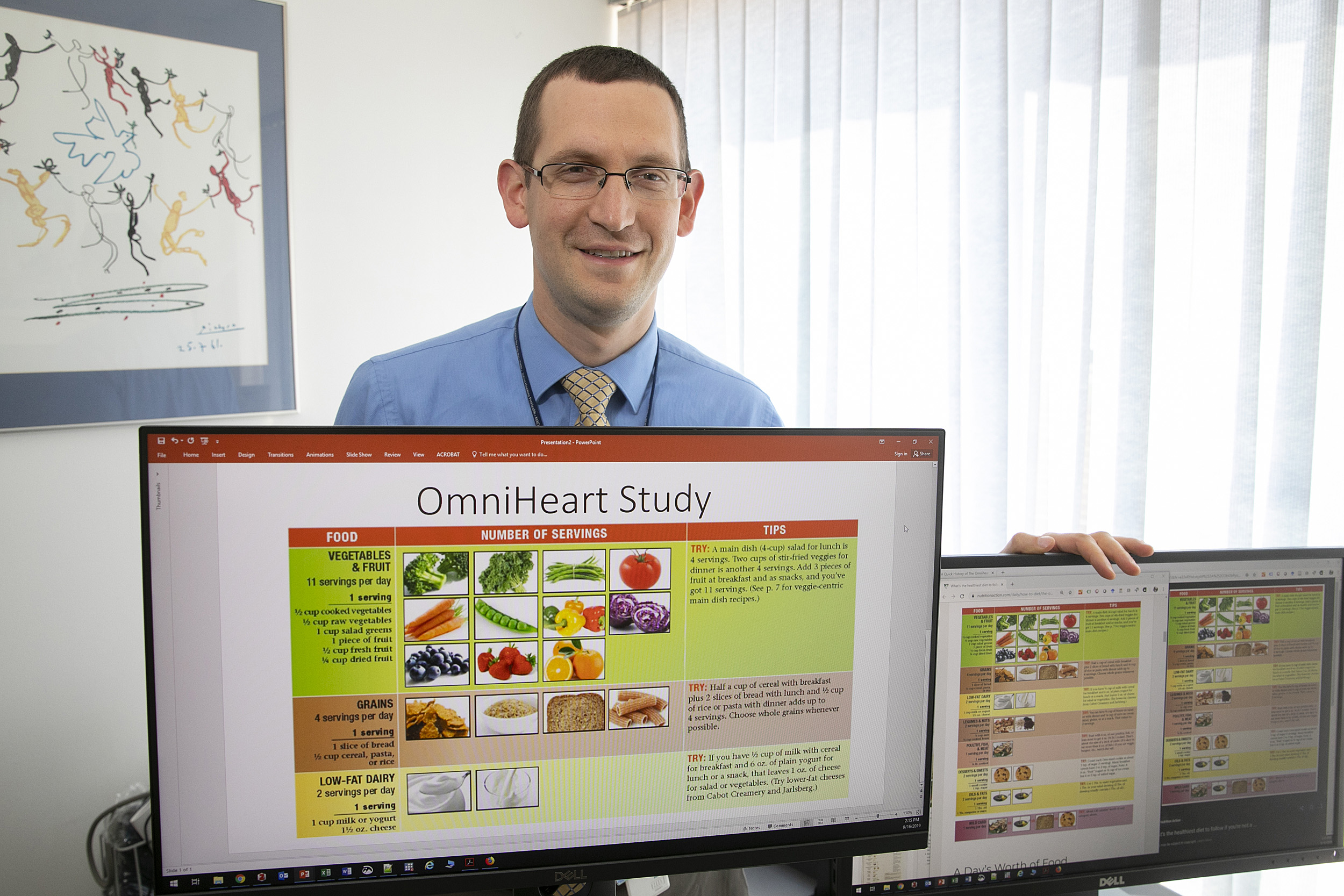

Stephen Juraschek is the senior author on a study showing that each of three different healthy diets help protect the heart.

Jon Chase/Harvard Staff Photographer

Protein, fat, or carbs?

Researchers show how several diets can improve heart health

Quick, which is healthiest diet? One focused on carbs, fat, or protein?

The answer? Any of them. Rebutting the breathless claims of the superiority of various fads, new research finds that consuming more carbs, fat, or protein can promote good health as long as they are part of an overall sensible and varied diet.

A team led by Stephen Juraschek at Harvard-affiliated Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center found that any of the diets could lead to a reduction in two chemical markers of heart damage. The improvements, which occurred over just six weeks, show that a fundamentally healthy diet can begin to make a difference in heart health almost right away.

“I have friends who talk all the time about the new trend diet. It used to be Atkins, now it’s Paleolithic and ketogenic. There are the people who hate carbs, the people who still hate fat,” said Juraschek, an assistant professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School. “The problem with all of these fad diets is that they overemphasize a certain macronutrient profile and underemphasize the importance of balance and heathy eating overall.”

While “eat healthy” may simplify the dietary message, the broader problem is that most of us don’t, Juraschek said. Despite decades of advice to the contrary, the typical American meal remains heavy on meat and carbohydrates — often heavily processed — with fruits and vegetables almost an afterthought. While the guidelines recommend Americans eat five servings of fruits and vegetables daily, the average American eats just 1.8, Juraschek said, and our two most common vegetables are potatoes — often in the form of french fries and potato chips — and canned tomatoes.

“Our reduction in cardiovascular mortality has stagnated. We as a population are not achieving a healthy lifestyle,” Juraschek said. “This is a population trend that we have not been able to improve upon in the United States.”

“We get so caught up in the macronutrients, we miss the quality of the diet, the balance of the diet, and the emphasis on fruits and vegetables. Let’s re-evaluate how we’re constructing our plate.”

Stephen Juraschek

The findings emerged from a new study in which researchers applied new tests to old blood samples from a key study on diet and heart health.

The original study, called OmniHeart, published its results in 2005 and investigated variations on a diet designed to lower blood pressure in middle-aged participants with either prehypertension or stage 1 hypertension. Its aim was to see whether higher levels of carbohydrates, protein, or unsaturatedfat could improve on the base diet’s performance. The researchers examined two risk factors for heart disease — blood pressure and cholesterol — and found that each of the diets improved those factors, though the higher-fat and -protein diets performed slightly better than the carb diet.

Each of the three experimental diets were designed to be healthy, including between nine and 11 servings of fruits and vegetables daily, as well as whole grains, beans, nuts, low-fat dairy products, unsaturated fats, moderate salt, and high fiber. It also featured lean proteins from meat, fish, and poultry, as well as some sweets. The increased macronutrient in each version of the diet also came from healthy sources: plant protein, unsaturated fats, and less-processed carbohydrates.

Juraschek said that one common critique of OmniHeart was that it was so short — just six weeks on each diet — that it is difficult to know whether those improvements in blood pressure and cholesterol actually could prevent heart attacks down the road. The new study, conducted with colleagues from the University of Massachusetts, the National Institutes of Health, Johns Hopkins University, and the University of Maryland — some of whom were investigators in the original study — took the analysis a step further.

In work published recently in the International Journal of Cardiology, researchers examined levels of troponin, a compound created by the breakdown of proteins in heart muscle, and C-reactive protein, a marker of cardiac inflammation. Both declined over each six-week feeding period, troponin by between 8.6 percent and 10.8 percent, and C-reactive protein by between 13.9 percent and 17 percent.

“We’re taking it a step further,” Juraschek said. “We’re looking at whether the diets directly influence cardiac damage. Not only do the diets reduce blood pressure, they reduce direct injury to the heart and they reduce inflammation.”

Consistent with the original study’s findings for blood pressure and cholesterol, the improvement in cardiac muscle injury was slightly better for those on the higher-protein and -fat diets, but the largest improvement by far, Juraschek said, came as participants switched from their everyday diet to the study diet — whichever one it was.

“We get so caught up in the macronutrients, we miss the quality of the diet, the balance of the diet, and the emphasis on fruits and vegetables,” Juraschek said. “Let’s re-evaluate how we’re constructing our plate.”

Research was supported by National Institutes of Health and Alpha Omega Alpha Postgraduate Award. Siemens Healthcare Diagnostics Inc. donated equipment that identified markers of cardiac injury.