When transitioning to teaching online, Professor Matt Saunders established a Zoom lecture (pictured) and formed smaller groups with six new discussion sessions.

Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

Early responses indicate shift to online classes going well overall

Some running into minor hitches, but others finding surprising benefits

This semester, Matt Saunders launched the biggest studio art class at Harvard. The class of 72 students in “Painting’s Doubt” met weekly to learn figure drawing and paint from still life. When the coronavirus outbreak forced Saunders to move the class online, he faced some fundamental problems.

“We lose a lot of the value of having students all together because an important part of learning in this class happens through the peer group,” said Saunders. For the first half of the semester, he framed each session and gave pointers about how to approach rendering the subject, but “students [could] see each other’s solutions, so we’re trying to figure out how to capture that energy.”

Saunders, Harris K. Weston Associate Professor of the Humanities and director of undergraduate studies in the Art, Film, and Visual Studies Department, is one of thousands of faculty members who had to adapt and innovate their courses to move them online following the evacuation of campus due to the COVID-19 global pandemic. Early reports suggest that the transition has gone well overall, though not without hitches. In some cases it has even presented some unforeseen opportunities and inspired new insights about teaching and learning.

“Over the past 3 weeks, IT staff have worked tirelessly with our University partners to move Harvard’s classes online,” said Anne Margulies, Vice President and University Chief Information Officer. “The scale of this change is truly extraordinary, and this week has seen all-time high numbers of users leveraging technology to teach, learn, and work online. We are pleased with the performance of our systems so far and even more impressed with how well our community has embraced using technology in new ways.”

Like many of his colleagues, Saunders had never taught online before, but mobilized to change assignments and other logistics over spring break.

On campus, students met for a 75-minute weekly lecture and a four-hour weekly studio section. Adapting “Painting’s Doubt” to the online classroom involved shipping supply kits of paint, canvas, and other items to students around the world and establishing a schedule of one Zoom lecture and six new discussion sections led by teaching assistants, during which students share and discuss their work, which is now done independently.

Instead of walking around the classroom for critiques of works in progress during studio time, Saunders and his teaching team formed smaller groups that will meet online for more individualized assignments and direction, based on mid-semester evaluations. While the shift has disrupted his original plans, Saunders says it also offers a chance for exploration beyond the campus bounds.

Elisa New, Powell M. Cabot Professor of American Literature, includes more of the resources she had developed over the past seven years as creator of the digital platform and TV series “Poetry in America.”

Photos courtesy of Verse Video Education/Poetry in America

“Because this is a Gen Ed course, it combines studio work with conversations and lectures about painting as a language that engages with the world,” said Saunders. “One of the [original] assignments was that we would go paint all together in Mount Auburn Cemetery, but now I am asking students to start scouting out where they are, thinking about this dislocation in place, finding themselves suddenly in a different situation,” and creating a work about the psychological space of that new location.

In the course “An Integrated Introduction to the Life Sciences: Genetics, Genomics, and Evolution,” which is required for life sciences concentrators, Hopi Hoekstra and her colleagues revised in-person lab components and recorded some elements of discussion and lecture for wider availability to students scattered across the globe.

“We are trying to keep the flow of the course very similar” to how it was before spring break, said Hoekstra, Alexander Agassiz Professor of Zoology in the Departments of Organismic & Evolutionary Biology and Molecular & Cellular Biology, curator of mammals at the Museum of Comparative Zoology, and a Howard Hughes Medical Institute investigator. “We still have pre-lab quizzes and post-lab assignments. It’s a balance between trying to keep everything similar to the rhythm that the students have gotten used to, while making these tweaks to try to keep that rhythm as engaging and interesting as possible.”

But how exactly can this done if students don’t have access to labs? One assignment called for students to collect biological sample from their environments, extract the DNA, and analyze the resulting data. Instead, Hoekstra and her team collected samples from items including a cellphone, a boot sole, and a dog’s toy, and recorded a teaching fellow modeling the DNA extraction process. The team sent the samples to an external lab for sequencing and sent the resulting data to students for analysis. They were then assigned to match each sample’s DNA profile to one in a database.

“Online teaching is very different from face-to-face teaching, and what I love about it is that you can layer in archival and visual materials in a way that is engaging and vibrant.”

Elisa New

With remote lab work, “even though [students] miss the part of doing the field biology, they still get to do part of the scientific process, which is very fun, because the answer is unknown and they’ll get to discover that themselves,” said Hoekstra. “We’re trying to make sure that they get the foundational information that they need [for future courses]. It is also a pretty exciting time to be thinking about genetics and evolution in the middle of a viral outbreak, because what they’re learning is being talked about in the news all the time and they’re learning how it works.”

For some, the online classroom was a more familiar environment. Elisa New, Powell M. Cabot Professor of American Literature, used spring break to retool the syllabus for her course “Migrations: Fictions of America” to include more of the resources she had developed over the past seven years as creator of the digital platform and TV series “Poetry in America” and as an instructor at Harvard Extension School and HarvardX.

“In my experience of teaching online, I have discovered that making asynchronous learning the foundation of a course, and layering in synchronous learning — that is, everybody together on a Zoom session — is a much more reliable way to make sure the whole class participates,” said New, who will be combining live conversations with videos, recorded lecture content, and Canvas prompts for class discussion. New also incorporated episodes from “Poetry in America” into weekly course content on topics including Civil War poetry and Midwestern modernism as seen in Willa Cather’s novel “My Ántonia,” and other cultural products.

“Online teaching is very different from face-to-face teaching, and what I love about it is that you can layer in archival and visual materials in a way that is engaging and vibrant,” she said, noting that even if other faculty don’t have established online teaching resources to use in their courses, flexibility in content and schedule can be useful in successfully adapting courses to a digital environment.

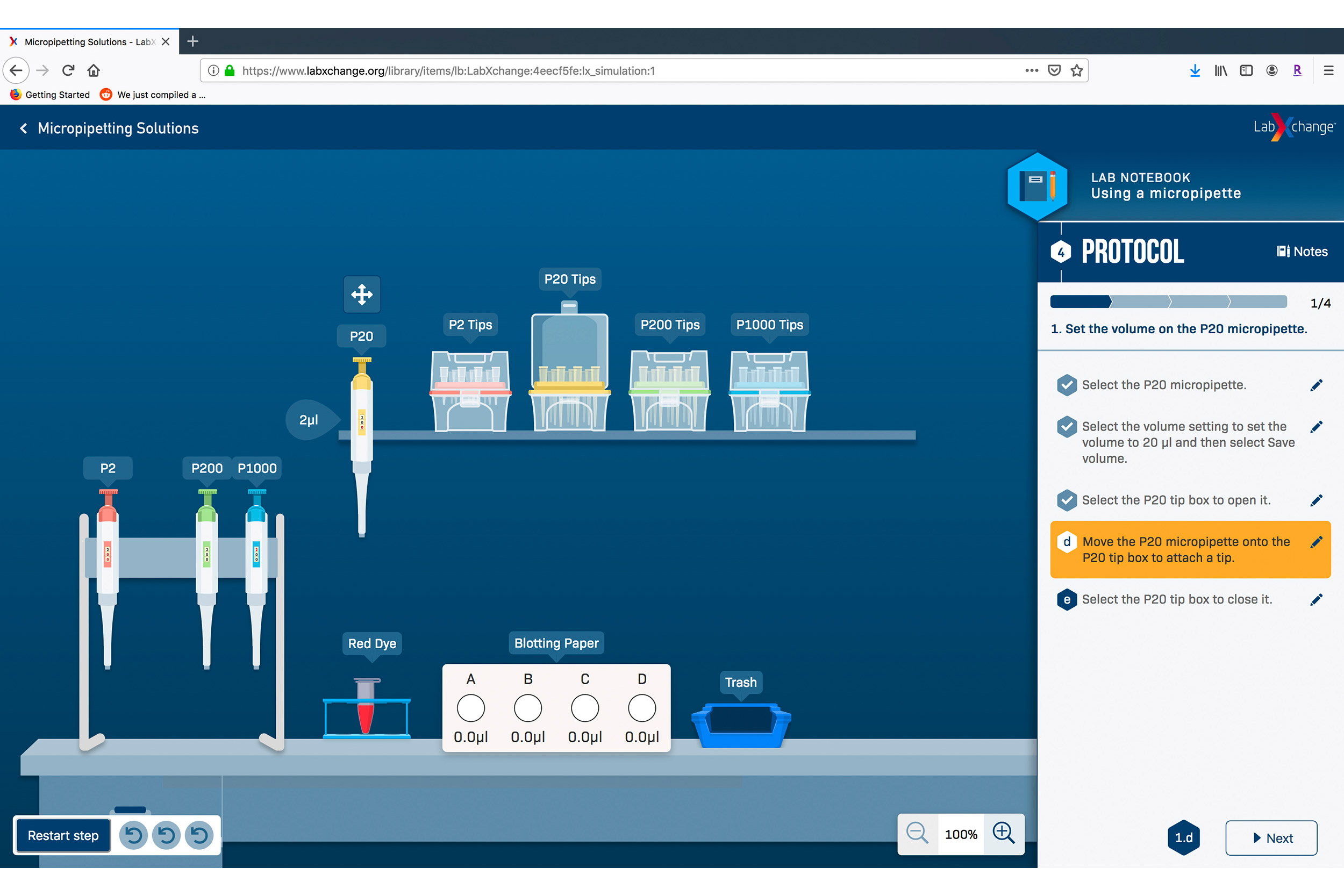

Professor of the Practice of Molecular and Cellular Biology Robert Lue echoed this sentiment. Lue, who is also faculty director of the Harvard Ed Portal, UNESCO chair on life sciences and social innovation, Richard L. Menschel Faculty Director of the Derek Bok Center for Teaching and Learning, and faculty director and principal investigator of LabXchange, combines live and recorded class meetings for his course “Cell Biology in the World.” He estimated that, so far, the Bok Center has reached more than 350 faculty members through online seminars and individual consultations to prepare for online teaching.

“It’s not just a matter of understanding what online can do for you, but the process of really interrogating your own assumptions and reexamining your course goals,” said Lue, who used LabXchange to record and present course content and also plans to conduct live Zoom sessions in Canvas. “What is really at the core? What is most important? What is the key thing that you want to get across [to students]? Sometimes we fall into particular patterns of doing things, and a shake-up like this really allows us to reassess what we’re doing.”

Saunders described the shift as a challenge, but said one silver lining of this experience “is that now we are embedded in the world.”

“We started the class with a text on Paul Cézanne, being outside of Paris, out in the village and working from life, and the idea of painting as an act of observation and engagement with the world around us. In the most general sense, we have a group of people who’ve developed a conversation together and new skills, and are now out all over [the world],” he said. “I hope they can report back in interesting ways and have some powerful encounters through the lens of painting.”