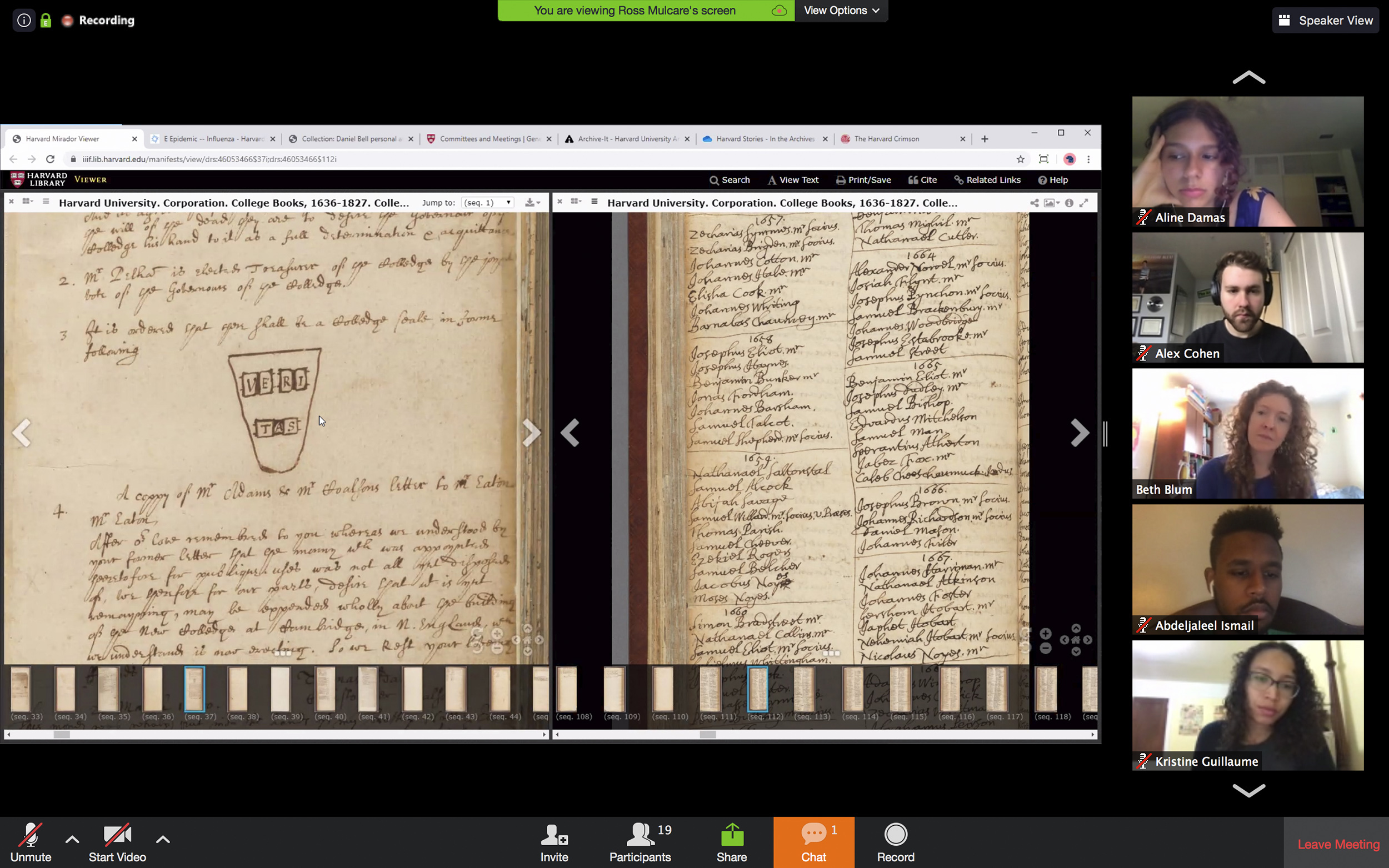

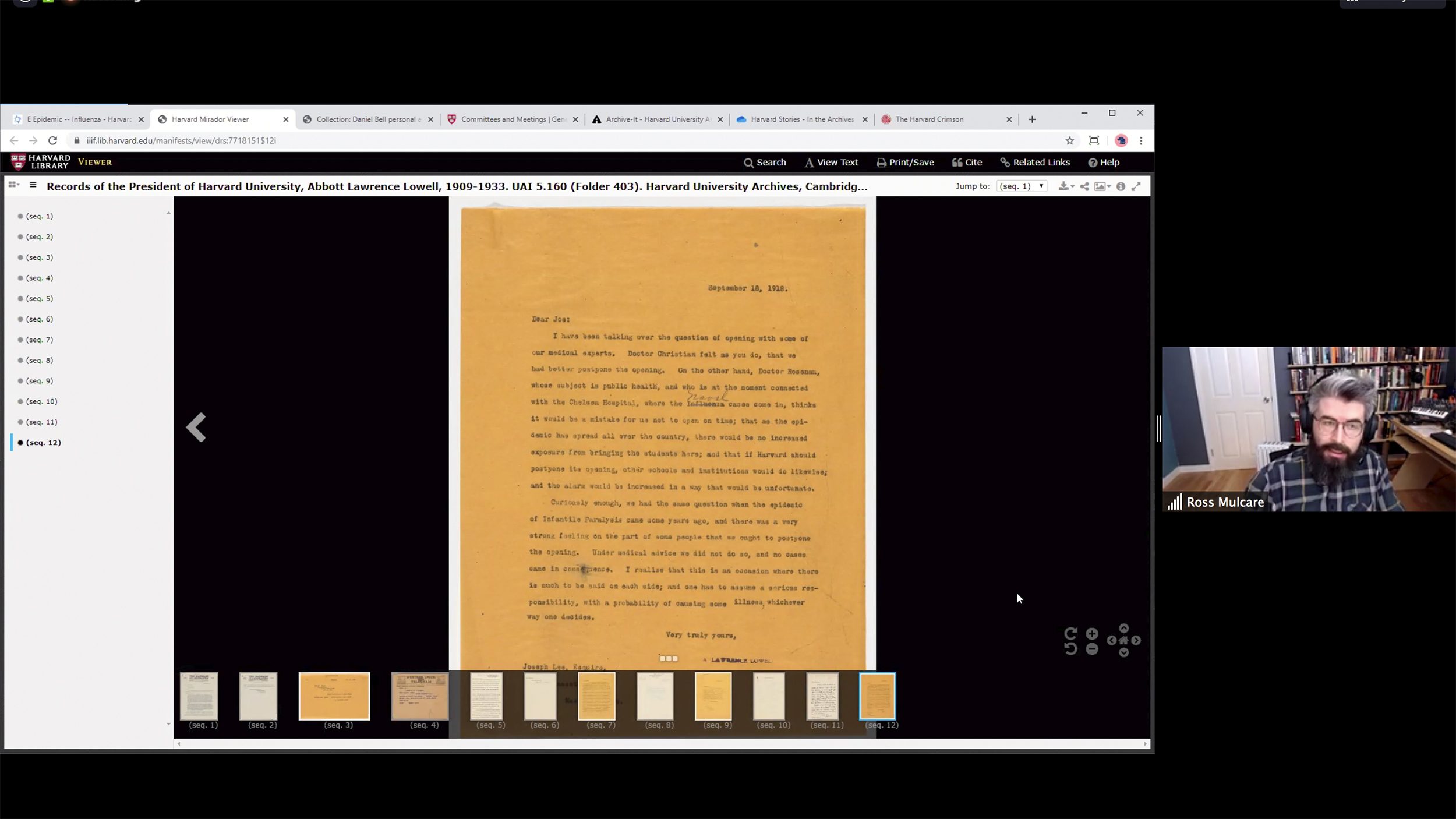

Students in the English course “The Harvard Novel” had a virtual class session centered around artifacts from the Harvard Archives, including a drawing of the Veritas shield and a list of students from the late 1600s featuring Caleb Cheeshahteaumuck, the first Native American to receive a Harvard degree.

Harvard, by the books

Blum’s course ‘The Harvard Novel’ takes students back to campus

It didn’t turn out at all the way they thought it would. Being asked to quickly leave campus and return home last month amid the mushrooming coronavirus outbreak was painful and disappointing. But the experience gave the students taking “The Harvard Novel” an additional personal, if unplanned, connection to what they were reading.

The narratives in the course often “describe what happens after someone gets to Harvard, both the exhilaration and the disillusionment that can occur with the realization of a new set of struggles or challenges that confront a person once they have actually arrived,” said Beth Blum, an assistant professor of English who created the class this year. “That ties in to [the students’] own feelings of having their expectations subverted by this experience and trying to manage that.”

Even before the evacuation there were already lots of touchpoints in the texts, which include Henry Adams’ 1907 autobiography “The Education of Henry Adams,” Elif Batuman’s 2017 novel “The Idiot,” and W.E.B. Du Bois’s 1960 essay “A Negro Student at Harvard.” Not so long ago students taking the course were living in the midst of landmarks such as Warren House, Widener Library, and the Adams House Senior Common Room, all of which served as settings for the literature they were studying about life at a storied University with a history of excellence and exclusivity.

“One really special thing about taking the course on campus was that we could read a text as we were literally living in the settings of those stories, [and] it was easier to be in the headspace of a lot of those characters just by being on campus and seeing how interactions at Harvard sometimes mirrored or diverged from their literary depictions,” said Kristine Guillaume ’20, a joint concentrator in history and literature and African and African American Studies, who is taking the course. “From a distance, that’s not possible. But it certainly is a way to stay connected to campus even from all of our different locations, so I’m happy to have a class that situates me in Cambridge whenever I’m reading.”

Before the coronavirus forced the University to put courses online, Beth Blum (standing) taught “The Harvard Novel” in her classroom. After spring break, she took it virtual.

Photo by Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

Making that connection between how both readers and literary characters are touched by the geographic, historic, and cultural moment in which they live makes the narratives feel personal and universal, and that’s one goal of the course. During recent online class meetings, students were able connect their Harvard-centric syllabus to current events. They compared the racism experienced by James Lee, a character in Celeste Ng’s 2014 “Everything I Never Told You,” to the stigma Asian Americans now feel from being associated with the coronavirus in some popular media, and discussed technology’s role in enhancing and restricting human interactions, through the introduction of email in “The Idiot,” set in the 1990s, and the Zoom interfacing that is now an everyday thing.

“It’s a cliché that the Harvard bubble feels unreal and removed from everyday life, and this experience has really exacerbated that feeling of unreality,” said Blum. “It’s really brought home a key concern of the course, which is how institutional dramas line up with broader-world historical crises, and how to balance an investment in the Harvard drama with a social conscience.”

Blum also worked with the Harvard Archives on a special class session on documents that tell real-life stories from the University’s history, including a class list featuring Caleb Cheeshahteaumuck, the first Native American to receive a Harvard degree in the late 1600s, and the personal archive of Plenyono Gbe Wolo, who received a bachelor’s degree in 1917 and was the first Harvard College student from the African continent.

The archive session supported some of the critical work done in the course to understand the experiences of Harvard community members who may have felt like outsiders.

“We’ve been paying a lot of attention to the experiences of women in these stories, to the experiences of people of color, [and] the experiences of those who may not be the 1 percent,” both among faculty and students, said Guillaume, a Lowell House resident now living at home in Queens, N.Y.

“My students are very incisive readers, and they’re very eager to find a good balance of appreciating the possibilities that being at Harvard enables and the great literary and aesthetic tradition that it’s produced, but without devolving into navel-gazing,” said Blum. “I think there’s a real desire on everyone’s part to balance appreciation and an eye for critique and improvement in terms of the history of Harvard.”

The virtual archives visit was also one of many projects that situate Harvard in the global community. Students created a collaborative digital map of relevant locations around campus that feature prominently in course texts: the Faculty Club, where a female character in the murder mystery “Death in a Tenured Position” experiences discrimination; Charlie’s Kitchen on Eliot Street, a site for Lee’s fixation on “American” food in “Everything I Never Told You”; and a Harvard-bubble-breaking running route to Porter Square by the protagonist, Selin, in “The Idiot.”

During the pandemic, students are writing regular “Quarantine Diary” entries on Canvas that Blum plans to submit to the Harvard Archives as primary documents for future generations to read. And for their final project, students will write either a traditional paper or the first pages of their own “Harvard Novel.”

“We’ve gone, very quickly, from being anthropologists of Harvard’s literary history to feeling like living embodiments of this very historical moment in Harvard’s history,” said Blum. “It’s something that I tried to channel into the course in a way that would actually allow us to record our own experiences and impressions of this moment, with an eye toward posterity and future interest in this time.”

For Guillaume, the course was a chance to look back on the past four years, as well as understand how her own story fits into the broader themes of success and the American Dream that pervade the course texts.

“Senior spring is a really reflective time, and seeing the campus depicted in these novels, and grappling with implications of being here and the experience of being a student, through literature, has been really valuable,” said Guillaume. “I grew up with two parents who are immigrants, and sending their daughters to top-tier colleges was a huge part of what it meant to achieve the American dream. I [like] grappling with the larger questions that I have about American achievement.”