Face to face with America’s original sin

Book confronts historical, ethical questions posed by Zealy daguerreotypes of enslaved people

In 1850 Harvard professor and biologist Louis Agassiz commissioned a study in scientific racism. The resulting images of Jem, Alfred, Fassena, Delia, Jack, Renty, and Drana, a group of people of African descent enslaved in South Carolina, are now known as the Zealy daguerreotypes and have become critical artifacts in the study of enslavement and racism in American history. The images were first discovered by the staff of the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology in the mid-1970s.

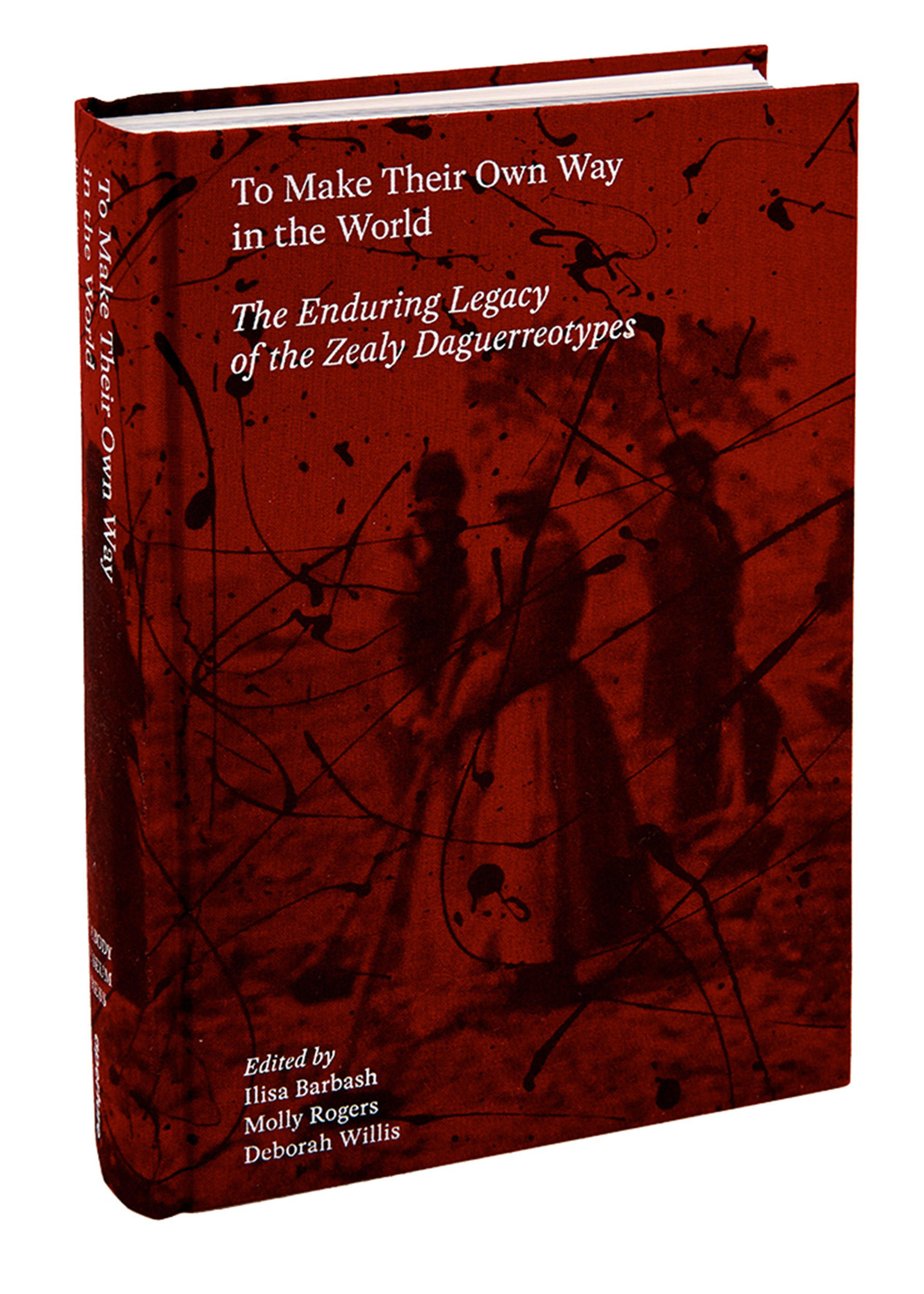

A new book co-published by Aperture and Peabody Museum Press, “To Make Their Own Way in the World: The Enduring Legacy of the Zealy Daguerreotypes,” focuses on the challenges and possibilities of examining these images. The volume is edited by Molly Rogers, Deborah Willis, and Ilisa Barbash, and features articles by Harvard faculty including Henry Louis Gates Jr., Sarah Elizabeth Lewis, John Stauffer, and Evelyn Brooks Higginbotham, and a photography series by artist Carrie Mae Weems.

In “To Make Their Own Way in the World,” the writers engage with the historical, artistic, and ethical questions that surround the daguerreotypes and offer avenues for understanding the role of these images in revealing the legacy of slavery in the U.S.

“If we are to be ethical stewards of the collections, we must acknowledge and engage with the complex history of the Peabody and anthropology generally. This is especially true as we confront highly sensitive objects like the Zealy daguerreotypes, which bring to life this devastating history and its impact on seven enslaved men and women,” said Jane Pickering, William and Muriel Seabury Howells Director of the Peabody Museum. “As the current stewards of these images, we need to provide a platform to ensure this dialogue takes place, collaboratively and transparently.”

The Gazette spoke to Barbash, curator of visual anthropology at the Peabody Museum, and Lewis, associate professor of history of art and architecture and African and African American studies, about their work on the book and their experiences of working with the daguerreotypes in teaching and research.

Q&A

Ilisa Barbash and Sarah Elizabeth Lewis

GAZETTE: This book has been in the works for many years and will be the first encounter with these images for many readers. Why is it so important to tell this story and collect these analyses of the daguerreotypes in a volume like this?

BARBASH: We’ve been working on this idea in some form or another since 2008, first with the thought of doing an exhibition and then holding workshops and a seminar at the Radcliffe Institute. The whole purpose of the book was to do as responsible and as thorough a job as possible to frame the daguerreotypes as they make their way out into the world. For many people, this is their first introduction to these images and their very difficult and complex history. But it was never intended that what we were doing would be the last word on the subject. This is the first word.

LEWIS: I was asked to be part of this book project when I first joined the faculty in 2015, and what I most appreciated was how collaborative the process was — we developed scholarship as a community. This was so welcome, particularly since we are in an urgent moment, and I would argue a perilous moment, in our country. This country has been in such moments before, yet this particular one has a distinct character. It offers near-daily reminders of the fragility of rights in the United States and how they have not only been secured by norms and laws, but by regard — how we quite literally see each other, and how we refuse to see each other. The reckoning of our current moment is impossible to understand without rigorous study of culture born of the ocularity of slavery and the history of so-called racial science. The Zealy daguerreotypes are indispensable for this understanding. It is why the work coming out of the Harvard & the Legacy of Slavery initiative, led by Tomiko Brown-Nagin, dean of the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study, is so important. It is perhaps impossible to grasp the nature of how slavery structured sight, regard, and citizenship in a racialized democracy without understanding the history and events that could have produced these images.

GAZETTE: The daguerreotypes are very difficult to look at and can provoke deep emotions and responses from viewers. In spite of these challenges, why is it important to examine and analyze them?

LEWIS: These images are some of the most important objects not only about the history of slavery in the United States, but also about the marriage of sight, regard, and citizenship in a racialized democracy. Without seeing these images, it is hard to understand why, for example, Frederick Douglass, along with Sojourner Truth, seized on the new photographic medium as a way to advocate for an expanded notion of citizenship and belonging. Their work anticipated a central theme in arts and humanities at large in American democracy: the function of visual representation, specifically, to create counternarratives as both evidence and critique and in civic society as a way to push back against dehumanization.

Sarah Elizabeth Lewis is associate professor of history of art and architecture and African and African American studies.

Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard file photo

BARBASH: I feel as if people have to see these images, or they have to be allowed to see these images. The first reason is because they exist, and the second is because I feel that the suffering of the people in these images started with slavery. The photography of them was demeaning, but because that has already happened, I do not want their suffering to have been in vain. And I think it is important for the public to look at them and acknowledge the complexity and all the rights and the wrongs of their existence.

GAZETTE: Professor Lewis, you regularly teach courses focused on the daguerreotypes. How do you prepare students to view them?

LEWIS: Every year, I do debate whether and how I should let students view them in my courses that engage in the history of photography, race, and citizenship. The men and women are all shown bare-chested and bare-breasted, half stripped, insistently revealed. These are not portraits, an image in which one has any agency or control. They are an early example of the transformation of pictures into data weaponized to support the societal boundaries in American life. The composition of the image also serves as an index of the violence of racial science. So, the main questions I ask myself when teaching are: How can we best honor sitters robbed of agency in their own portrayal? How can we best create the society that should come after a reckoning with this history?

Teaching with the Zealy daguerreotypes, whether in HUM 20, American Racial Ground, or my “Vision and Justice” Gen Ed course, requires an enormous amount of preparation on the level of pedagogy and beyond. Bringing students to see them at the Peabody Museum means getting ready to witness them leaving that room altered in ways that go beyond their intellectual growth. I am often witnessing students who have had their ethics and principles challenged and even newly defined as well. In fact, there is a wonderful essay in this volume by [Dillon Professor of American History and Professor of African and African American Studies and of Studies of Women, Gender, and Sexuality] Robin Bernstein and Harvard students about [seeing and] teaching from the Zealy daguerreotypes. Inevitably, the questions that come up for them are about access, ownership, legacy, and lineage. What I think I’ve seen most of all is that viewing these objects makes the students ask questions about themselves regarding how they can best contribute to the creation of a more just society.

“To tap into the fact that you have this person staring back at you over 170 years makes the evils of slavery so much more real.”

Ilisa Barbash

GAZETTE: Ilisa, you are a curator and visual anthropologist. How have you engaged with these images over time, within the space of the museum?

BARBASH: I have trained as a visual anthropologist, so I am an image-maker and a filmmaker. It has always been very important to me to have consent of the subjects of my work and have them collaborate to an extent in their own representation. With the daguerreotypes, everything happened so long ago, and it’s the clear that consent wasn’t there. So what do I, as a curator, do about the fact that the reason these images came into being was because of slavery and scientific racism? How do I make sure that these images of people are not used for commercial purposes, are not used in a way that is disrespectful?

One of the major tenets behind anthropology is that you protect those people at the core of a research project. So I took that very seriously when considering how to frame these daguerreotypes or grant permission to people who wanted to use the pictures. I went through a few years of protecting them, so it was important for me in my article to explore the policies behind protecting them and to look at how artists use the images in a way that allows them to resonate more with people. You see that with Carrie Mae Weems’s work “From Here I Saw What Happened and I Cried,” which is centered on the images. In her case and with other artists, the artistic interpretations of the daguerreotypes were more impactful than the usual written scholarly interpretations.

GAZETTE: What do you hope readers will gain from the volume?

LEWIS: The Zealy daguerreotypes offer a clear, chilling example of how representation and vision have been structured and conditioned in a representative democracy built on an ideal of freedom that was constructed, supported, and enriched by the thoroughgoing support of enslaved labor on stolen Indigenous land. It is one thing to discuss this as an idea. It is another to see the evidence in front of you. These objects contain this braided history. I cannot possibly convey fully how much preparation and processing it takes to teach with and research them, but it has been my experience that knowing about them leaves students forever changed in the best possible way.

BARBASH: I hope readers will be able to see these seven brave people as individuals, first, and then as people caught up and exploited by the horrific institution of slavery. We wrestled with the idea of how to present the daguerreotypes of them in the book. We felt that it was important to present them in a kind of gallery, where people can look at them and engage with them in a slow, personal, and measured way. On the right side of the page, you have the life-size version, and on the left, you have a smaller version of the daguerreotype in the open case. As nefarious as their original purpose was, they allow people of today and in the future to see what enslaved people really looked like. To confront that and to tap into the fact that you have this person staring back at you over 170 years makes the evils of slavery so much more real.

Interviews were gently edited for clarity and length. Ilisa Barbash will lead a discussion on “To Make Their Way in the World” with John Stauffer, Professor of English and of African and African American Studies, Sarah Elizabeth Lewis, and Deborah Willis at a Harvard Book Store virtual event on Oct. 23 at 7 p.m.