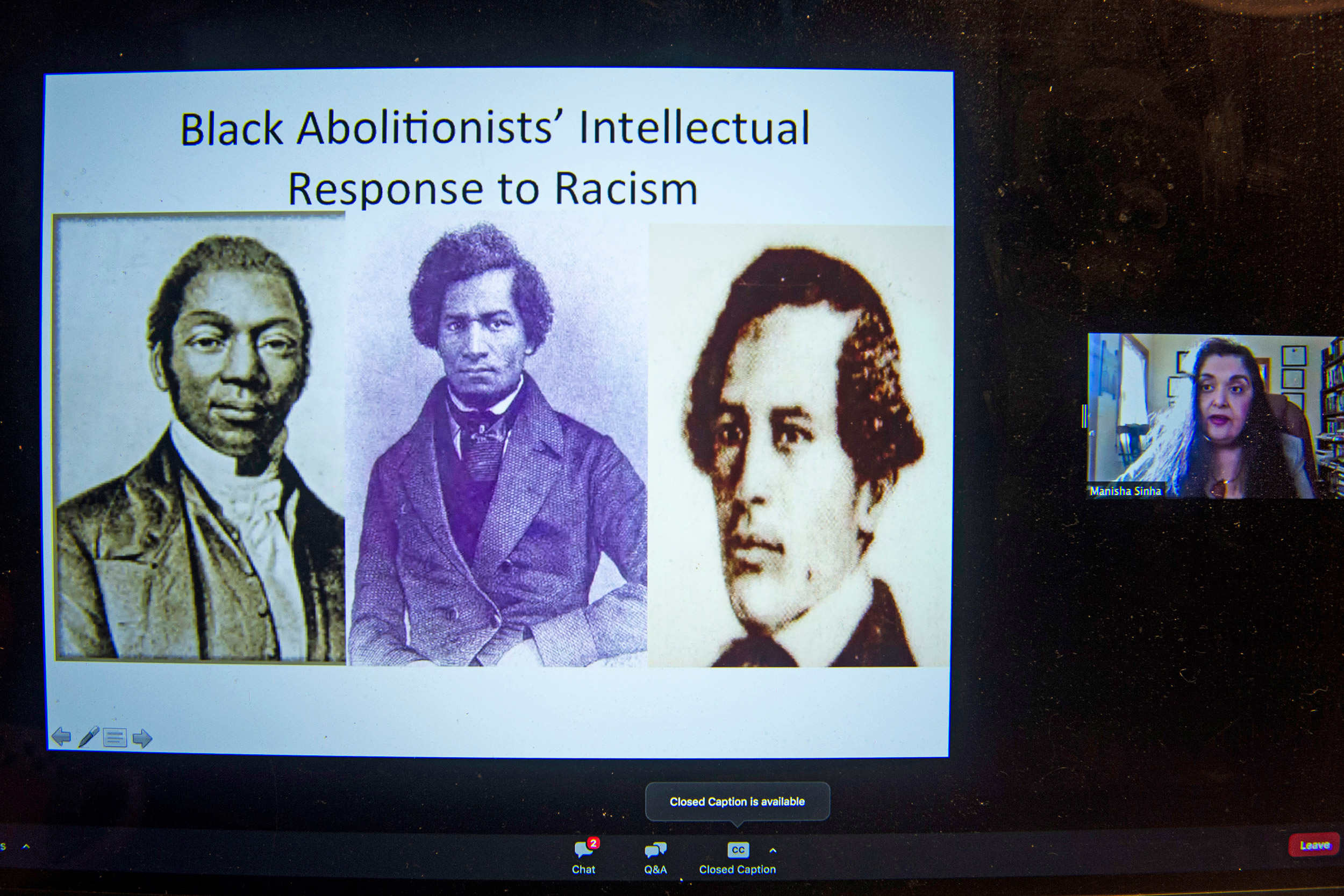

University of Connecticut Professor Manisha Sinha spoke about African American intellectuals James W.C. Pennington, Frederick Douglass, and William Wells Brown who, she says, often offered ethical and moral arguments against scientific racism.

Photos by Jon Chase/Harvard Staff Photographer

Exploring the North’s long history of slavery, scientific racism

Webinar upends myth of region’s blamelessness, reveals depth of issue in U.S.

Today they are seen as emblematic of the depth of American racism. But in their day and for a century beyond, the familiar but unsettling 19th-century daguerreotypes of Jem, Alfred, Delia, Renty, Fassena, Drana, and Jack were accepted in some circles as scientific evidence of the inherent inferiority of Blacks.

A Thursday afternoon webinar, “The Enduring Legacy of Slavery and Racism in the North,” took as its starting point a new book on the images, “To Make Their Own Way in the World: The Enduring Legacy of the Zealy Daguerreotypes,” co-published by the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology and the Aperture Foundation. The webinar examined the role of slavery in the North through the 19th century and the influence of Agassiz and scientific racism.

The daguerreotypes, commissioned by Harvard Professor Louis Agassiz to support his theories of human origins and found in the attic of the Peabody in 1976, represent “vivid and visceral records of our country’s original sin,” according to the book’s preface. Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study Dean Tomiko Brown-Nagin quoted it in introducing the panel: Kyera Singleton, executive director of the Royall House and Slave Quarters in Medford; John Stauffer, Sumner R. and Marshall S. Kates Professor of English and of African and African American studies; and Manisha Sinha, James L. and Shirley A. Draper Chair in American History at the University of Connecticut.

This program was presented as part of the presidential initiative on Harvard and the Legacy of Slavery, a University-wide effort housed at the Radcliffe Institute.

The images are symbolic of Harvard’s own entanglement with slavery, Brown-Nagin said. “For too long, Americans in the north of this country have cherished a narrative about widespread Northern opposition to the institution of slavery — privileging those stories over a more accurate and complete narrative about the ways that many Northerners were complicit in, and benefited from, slavery.”

Disturbing material like the Zealy images are crucial to understanding the historical picture, said Singleton, who is a doctoral candidate in American culture at the University of Michigan. “I want you to think about the violence of forgetting, of not seeing.” She cited statistics to bear out the role of slavery in the Northern economy: By the 1670s more than half the ships in Boston Harbor were slave ships, and enslaved people represented 12 percent of the population in Boston, and as much as 25 percent in Rhode Island.

She said the deeper truth is more than a matter of numbers. “How does one tell a complex story of slavery? At our museum, we know that some 60 people were enslaved by the Royall family. We know their names, but we don’t have a ton of information of who they were and how they felt.” To fill out the story, the museum made an archaeological dig that uncovered game pieces, smoking pipes, and other artifacts of the slaves’ everyday lives. “One cannot talk about the beautiful colonial mansion of the Royall family without talking about the people who built it, or the indigenous land it sits upon. … Who was enslaved against their will to generate enormous wealth for a white family?”

Stauffer looked deeper into Massachusetts’ decidedly mixed record on racism. On one hand, African American males during the Civil War had unrestricted suffrage, a privilege not granted to Irish immigrants. Massachusetts, which abolished slavery in 1783, was also the first state to overturn the ban on interracial marriage, the first to desegregate schools, and the first to admit Black jurors. And at Harvard, the first African American instructor, Aaron Molyneaux Hewlett, was a popular campus figure and the first Black superintendent of physical education.

“One cannot talk about the beautiful colonial mansion of the Royall family without talking about the people who built it, or the indigenous land it sits upon.”

Kyera Singleton, executive director of the Royall House and Slave Quarters

Yet it was also in Massachusetts that Agassiz pursued his racism through most of the 1800s, despite some pushback from the religious community, which noted that his theory of separate races contradicted Genesis. (“He said that the Bible did not include all the Genesis stories, which was a creative but problematic way of getting around that,” Stauffer said.)

Agassiz maintained friendships with the poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow and Sen. Charles Sumner, both public abolitionists who failed to dispute his views in public — though Sumner did in letters, Stauffer said. He suggested that they may have been reluctant to challenge the intellectual community in Boston. “It is fascinating to me that some of his anti-slavery colleagues do not confront him, which would have led to an important and rich discussion at the time.”

Sinha expanded on the “afterlives” of Northern slavery. Agassiz, she said, was only one of many 19th-century “scientific racists” who employed quasi-scientific reasoning to argue against Black rights. “They were measuring peoples’ skulls, the distance between their nose and their heads, and making pernicious claims about inherent racial inferiority. Whether it’s intellect, beauty, sensibility — you name it, they made those claims.”

In response, African American intellectuals — James W.C. Pennington, Frederick Douglass, William Wells Brown — often took the high road, offering ethical and moral arguments against scientific racism. Black women would use themselves to challenge stereotypes, such as Sojourner Truth’s wearing Quaker garb, Sinha said.

Nonetheless, the notion of an “American aristocracy of skin” persisted well into the 20th century. Not until the 1930s did racist academic theories largely fall out of fashion —despite the facts, Sinha said, “that only did [the abolitionists] have the better ethics and morality, they also had the better science.”