Tracing misinformation

Research shows elites, mass media play important role in spreading misinformation on mail-in voter fraud

Graphic by Lydia Rosenberg

Voter fraud by mail-in ballots is rare. Yet claims of “mail-in voter fraud” are spreading through mainstream media, cable and local television, and on social media sites in the lead up to the 2020 U.S. presidential election.

A new report from Harvard Law School Professor Yochai Benkler ’94 and a team of researchers from the Berkman Klein Center for Internet & Society shows that this disinformation campaign — intentionally spreading false information in order to deceive — is largely led by political elites and the mass media.

The report also shows that President Donald Trump, the Republican National Committee, Republican officials, and other public figures are central to fueling the dissemination of and attention to voter fraud claims online.

“We recognized the narrative that Donald Trump starting spreading earlier this year was going to play a significant role in the turnout and legitimacy of the 2020 election,” said Benkler, the Berkman Professor of Entrepreneurial Legal Studies and co-director of the Berkman Klein Center. “Surveys are telling us that concerns of voter fraud are disproportionately held by Republican voters, which is reflective of the deeply asymmetric media ecosystem, as we showed in our work on the 2016 election. This false narrative may have critical implications for the outcome of the 2020 election and democracy at large.”

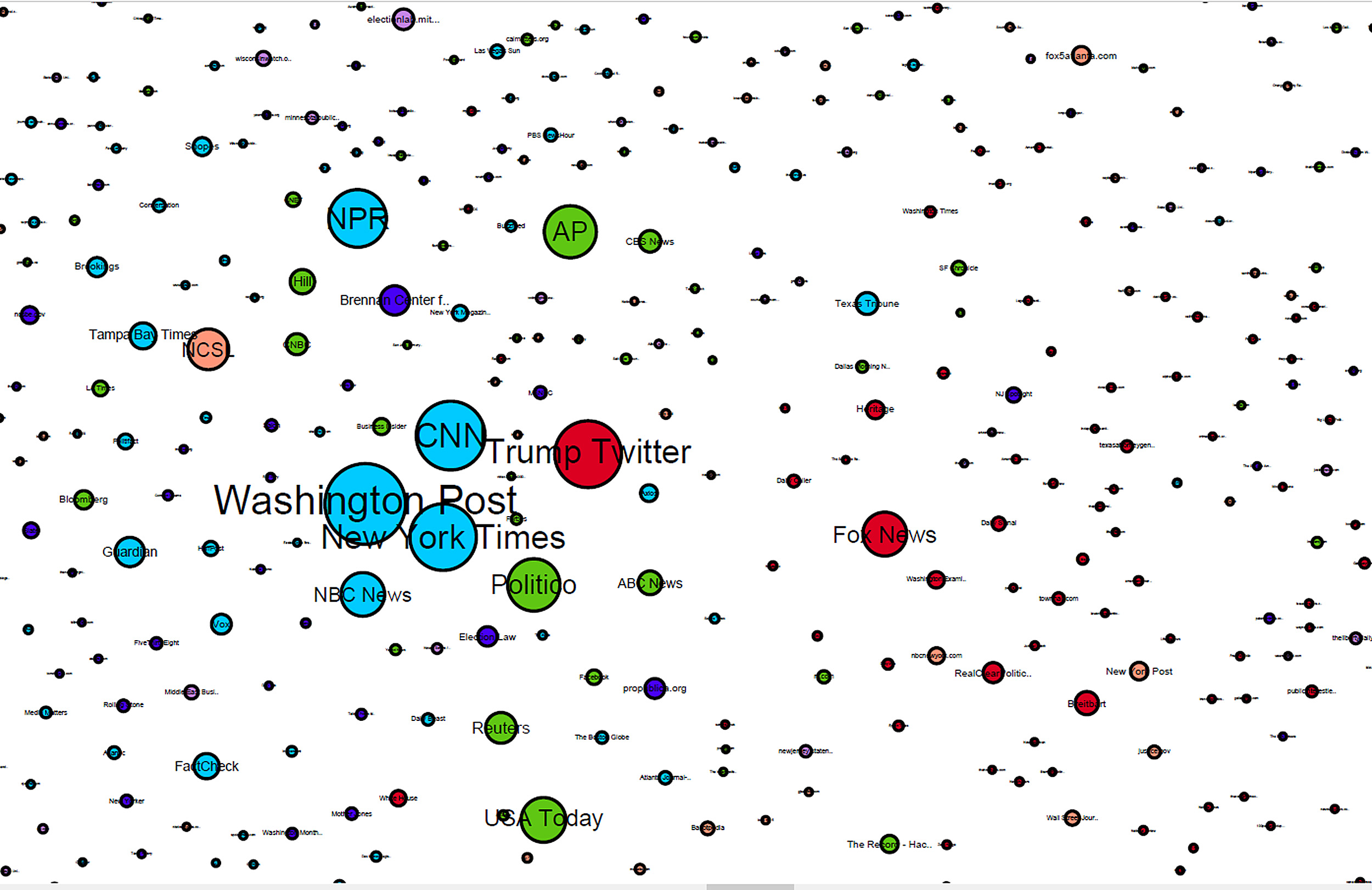

The size of each node in this network map is determined by the number of times it is linked to by other media outlets, representing their influence in the discourse around mail-in voter fraud. Their proximity is based on linking patterns.

Credit: Image courtesy of Yochai Benkler et al. under CC-BY-NC

Using Media Cloud, an open-source tool that provides access to data from online media sources, as well as data from Twitter and public Facebook posts, the team used quantitative and qualitative methods to trace and analyze the discourse surrounding voter fraud in the U.S. media ecosystem.

This method revealed that throughout the media ecosystem, conversations about voter fraud, in online news, Twitter, and Facebook, largely followed an agenda set by Donald Trump through tweets, media appearances, and press conferences.

First, the team created network maps to illustrate the relationships between media outlets across the political spectrum. The team used data from Twitter to characterize the audience mix of different media outlets divided into quintiles: left, center-left, center, center-right, and right. One of the maps they share is based on linking data from online media outlets.

In addition to showing how Fox News and right-wing media still exist in their own, distinct cluster, while the rest of the media ecosystem, from the center to the left, forms a single connected ecosystem, it also highlights how central Donald Trump’s Twitter account is to discourse about mail-in voting fraud.

“What we found striking from this network map in particular is the placement of Donald Trump’s Twitter account closer to center and center-left leaning media outlets. This image captures how well the president was able to command coverage and set the agenda of American public debate over mail-in voting, communicated through major media outlets like CNN, the Washington Post, the New York Times. It also emphasized the large impact of syndicated news producers like the Associated Press and NPR,” said Benkler.

“This false narrative [about voter fraud] may have critical implications for the outcome of the 2020 election and democracy at large.”

Yochai Benkler

The qualitative component looks at the content and rhetoric spread from March through August, digging into the top tweets, public Facebook posts, and online articles about voter fraud during these time periods. It also accounts for critical examples of voter fraud shared on cable TV news from political hosts. Through this analysis, the researchers again found that Donald Trump, members of the Republican National Committee, Republican officials, and other public figures were strikingly prominent in tracing the peaks of attention paid to the false voter fraud narrative.

Benkler and the research team found that the disinformation campaign, led by Donald Trump and the Republican party, was also enabled by practices of objective journalism which favor neutrality and sharing perspectives from “both sides.” This approach is failing, the researchers argue, because it’s further spreading the false voter fraud narrative in a flawed attempt at “balanced” reporting.

“We constantly talk about social media disinformation, Facebook fact checking, or counterintelligence against Russian interference. But our research suggests that these play a secondary role in the most important disinformation campaign likely to affect voter participation and public perceptions of legitimacy of the election’s outcomes,” Benkler said.

Instead, as the report concludes, “it will be critical for editors of these national and local media, particularly on the television stations trusted by the least politically pre-committed and often least politically attentive citizens not to fall for the strategy that the president has used so skillfully in the past six months, not to capitulate to the inevitable charges of partisanship that will befall any journalists and editors who call the disinformation campaign by its name, and not to add confusion and uncertainty to their readers, viewers, and listeners by emphasizing false equivalents or diverting attention to exotic, but according to our research, peripheral actors like Facebook clickbait artists or Russian trolls.”

The research team, in addition to Benkler, includes Casey Tilton, Bruce Etling, Hal Roberts, Justin Clark, Robert Faris, Jonas Kaiser, and Carolyn Schmitt.