Rose Lincoln/Harvard Staff Photographer

Hard lessons from a tough election

Scholars and analysts reflect on politics, divisiveness, diversity, and disinformation

It was a presidential election befitting the past four years, unprecedented and contentious. Temperatures ran high on both sides, fueling turnout estimated to be the highest since 1900, when 73.7 percent of the electorate cast ballots. Younger voters, age 18‒29, made their voices heard in historic numbers, and mail-in voting broke records in states around the nation, owing largely to health concerns over the pandemic. Battle lines were drawn over the handling of the COVID-19 outbreak and resulting economic fallout; national protests over racial inequity; the future of the Affordable Care Act; climate change; and Supreme Court nominees.

Each side accused the other of promoting unfair election tactics. Democrats urged voters to mail in ballots and to vote early, citing concerns over the coronavirus, changes at the Postal Service that could slow delivery, and shifting rules in Republican-controlled states that could make in-person voting or dropping off absentee ballots an hourslong process. Republicans sought to limit the collection and counting of mail-in ballots, voicing concerns about the prospects for widespread voter fraud. Party officials offered no evidence to support their suspicions.

The threat of foreign interference and disinformation campaigns from both inside and outside the nation hung overhead. In late October U.S. intelligence and law enforcement officials held a press conference to warn that Russia and Iran had obtained some voter registration information and would seek to incite social unrest through emails and other means, although there is no evidence that foreign powers managed to tap directly into actual voting systems and change outcomes. Researchers suggested that when all the dust settled it could very likely turn out that most of the election disinformation came from domestic extremist groups and trolls via social media.

The election was viewed by all, including leaders here on campus, as consequential. “For many people, the U.S. election has brought the trials and tragedies of this year into even sharper focus. All of us who have an opportunity to vote in a well-functioning democracy can use that opportunity to help address the problems we see in the world,” President Larry Bacow said in a letter to the Harvard community last Friday.

The Gazette asked scholars and analysts across the University to reflect on lessons learned in a variety of areas.

Kris Snibbe/Harvard file photo

Harvard University

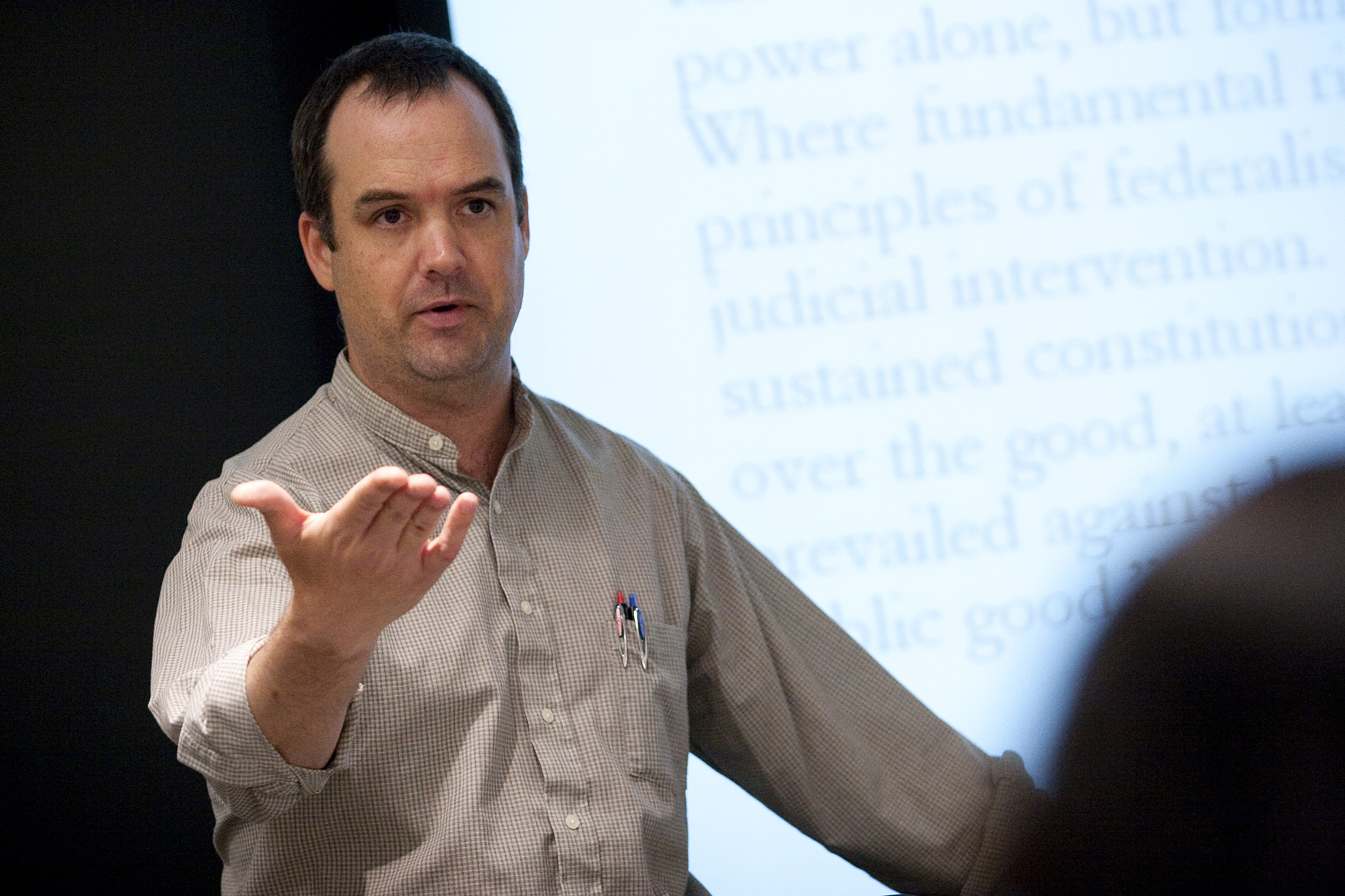

Ryan Enos

Professor of Government at the Department of Government

GAZETTE: What should we take away from the election overall?

Enos: From this election we’ve learned that our system is not working and is in need of major reform.

In this election, we have had voters with a legitimate fear of violence during or in the aftermath of the election; politicians undermining confidence in the electoral process; voters concerned their votes wouldn’t be counted; politicians attempting to prevent them from being counted; and talk of whether we will have a peaceful transfer of power.

A democracy cannot long function under these conditions, and that these are not just fringe concerns shows that the institutions designed to prevent these threats to democracy are not functioning as they should.

Kris Snibbe/Harvard file photo

Harvard University

Tomiko Brown-Nagin

Dean of the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study

GAZETTE: What should we take away from the election overall?

Brown-Nagin: This election crystalized American promise and American peril. Fifty-five years after passage of the Voting Rights Act and 100 years after ratification of the 19th Amendment, the fundamental right to vote — the essence of a democracy —remains ferociously contested and deeply cherished.

Turnout was extraordinary! An estimated 67 percent of eligible voters cast ballots — almost 160 million people — the greatest number in more than 100 years. Voters mailed ballots or cast them in person, notwithstanding the global pandemic. The electorate included large numbers of women and racial minorities, some mobilized by the prospect of electing Kamala Harris, who would be the first South Asian and African American woman vice president.

At the same time, we witnessed a concerted effort to suppress the vote, to intimidate voters, and to delegitimize legally cast votes. And the results revealed an electorate divided in all sorts of ways — by region, race, ethnicity, gender, class, religion, education level, and generation. An overwhelming majority of African Americans, Latinos, and Asians, and a sizeable majority of young people and gay, lesbian, and transgender Americans — highly motivated by concerns about health and racial inequality — voted for the Democratic candidate. By contrast, sizeable majorities of white, evangelical Christian, rural, and non-college-educated voters mobilized around security and the economy and chose the Republic candidate.

All this occurred a mere 12 years after we witnessed the apotheosis of the Voting Rights Act’s vision of multiracial democracy: the election of President Barack Obama, a biracial man, by a cross-racial coalition of voters, including whites without college degrees, who lived in all parts of the country. That historic moment generated a backlash and a threat to democracy itself; now some Americans, including some bearing arms, are demanding that officials stop counting votes. The 2020 election starkly revealed an enduring struggle for a more perfect union amid threats to popular sovereignty and demands to live up to our nation’s founding commitments.

Sandy Levinson

Visiting Professor of Law at Harvard Law School

GAZETTE: What should we take away from the election overall?

Levinson: What we learned was that the uncertainty of this election is entirely a function of the crazy way that Americans elect their president, which is through the Electoral College. This means, for example, that [President] Trump gets nine electoral votes for carrying the two Dakotas plus Wyoming, which collectively have only about 200,000 more residents than New Mexico, which contributed only five votes.

What remains an “interesting” question, if one is an academic, is why Americans persist with such a truly dysfunctional system of presidential election. One answer is provided by Harvard Kennedy School Professor Alex Keyssar in a book aptly titled, “Why Do We Still Have the Electoral College?” The answer, basically, is that the U.S. Constitution is next to impossible to amend, not least because the framers, with their distrust of popular government, provide no mechanism for doing end runs around a sclerotic Congress by organizing popular initiatives and referenda, as are allowed in roughly half the American states and in a number of foreign countries such as New Zealand and Switzerland.

One thing that is also worth noting is that the major split in America is less that between “red states” and “blue states” than between cities and less-urban areas. Texas, where I live, is a very blue state consisting of four of the 11 largest cities in the U.S. and an equally red state in the rest of the state. This is also obviously true in Pennsylvania, Michigan, and most of the larger states. Were we simply divided between red and blue states, then I think it might be wise to consider the possibility that secession would emerge as a genuine possibility. (Several books, by both left- and right-wing authors, have seriously addressed the possibility.) But it is really not conceivable that states will dissolve into their urban and rural territories. All one can say with confidence is that the polarization that is one of the defining features of contemporary American politics continues absolutely unabated.

Kris Snibbe/Harvard file photo

Harvard University

Jennifer Hochschild

Henry LaBarre Jayne Professor of Government and Professor of African and African American Studies

GAZETTE: What should we take away from the election overall?

Hochschild: We learned that Donald Trump’s victory in 2016 … tapped into a real, important, scary (to me) sense of anger and displacement, as well as nationalism, religiosity, racism, and economic need that Democrats have been largely clueless about. The urban/rural (or coastal/center, or cosmopolitan/localist) divide is big and won’t go away easily. Trump reinforced the gap; Biden wanted to close it. Democrats have a lot of hard work and self-examination to do, and Republicans want to lock down a minority-run government. It’s not pretty, all around. I don’t know, of course, but I would guess that by now, Trump’s lies and posturing don’t make a lot of difference, in the sense that he has done about as much damage as he can do to norms of democratic discourse and truth-telling (which is a lot of damage).

Trump will surely encourage and provide more misinformation, and I think the push to litigate, to declare the outcome of the election to be “stolen” and illegitimate is indeed pretty dangerous. But I don’t think we can explain or explain away Trump’s strong support as merely misinformation — 80 million people aren’t that stupid. There are two distinct and contradictory information networks [in operation], however, which is a slightly different point. The media that Trump opponents read focuses on COVID, immigration, racism, lying, corruption. The media that Trump supporters read focuses on abortion, jobs, economic growth, protecting the borders, political correctness, dangerous cities, and religious faith. Both sets of information may be equally true, but they barely overlap. I think that is a more serious, broader, problem than misinformation per se.

Kris Snibbe/Harvard file photo

Harvard University

Michelle A. Williams

Dean of the Faculty, Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, and Angelopoulos Professor in Public Health and International Development

GAZETTE: What should we take away from the election overall?

Williams: That the American people still believe in democracy. Photos and videos showing long lines of voters were maddening, to be sure — voter suppression is an ongoing threat to our elections —but it was also heartening to see so many millions of Americans determined to exercise their constitutional right to cast a ballot. The record-breaking turnout numbers this year reaffirm a dearly held fact — that voting is a right Americans are no longer taking for granted.

I know that a lot of us are struggling with the fact that so many millions of our fellow citizens voted for such an amoral, unethical candidate. But this election has also reminded us that democracy is dynamic rather than static, and dependent on the ongoing, everyday actions of everyday Americans. As John Lewis reminded us, “Democracy is not a state. It is an act, and each generation must do its part to help build what we called the Beloved Community, a nation and world society at peace with itself.” In other words, this election is a starting point, not an end one.

Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard file photo

Harvard University News Office

Daniel Carpenter

Allie S. Freed Professor of Government

GAZETTE: What should we take away from the election overall?

Carpenter: I think we’ve learned that there is strong and widespread popular opposition to President Trump. The Democrats kept the House, may have expanded their membership in the Senate, and possibly have defeated an incumbent president. The advantages that incumbent presidents have are real. President Trump is the first incumbent president to lose the popular vote in his re-election campaign in almost three decades, since George H. W. Bush in 1992. Of course Trump did not win the popular vote in 2016 either, but then neither did George W. Bush in 2000, and Bush went on to win the popular vote in 2004.

But I also think we’ve seen the Republican Party coalesce even further around the politics of white resentment and, relatedly, opposition to a set of people called “elites,” which includes everything from lower-paid civil servants and public health workers to government scientists and more-educated populations. This troubling force is going to be with us for a long time. The countervailing force is the diversity and energy of younger Americans, who have the chance to redefine American democracy in the coming generation.

Jon Chase/Harvard file photo

Jon Chase/Harvard Staff Photogra

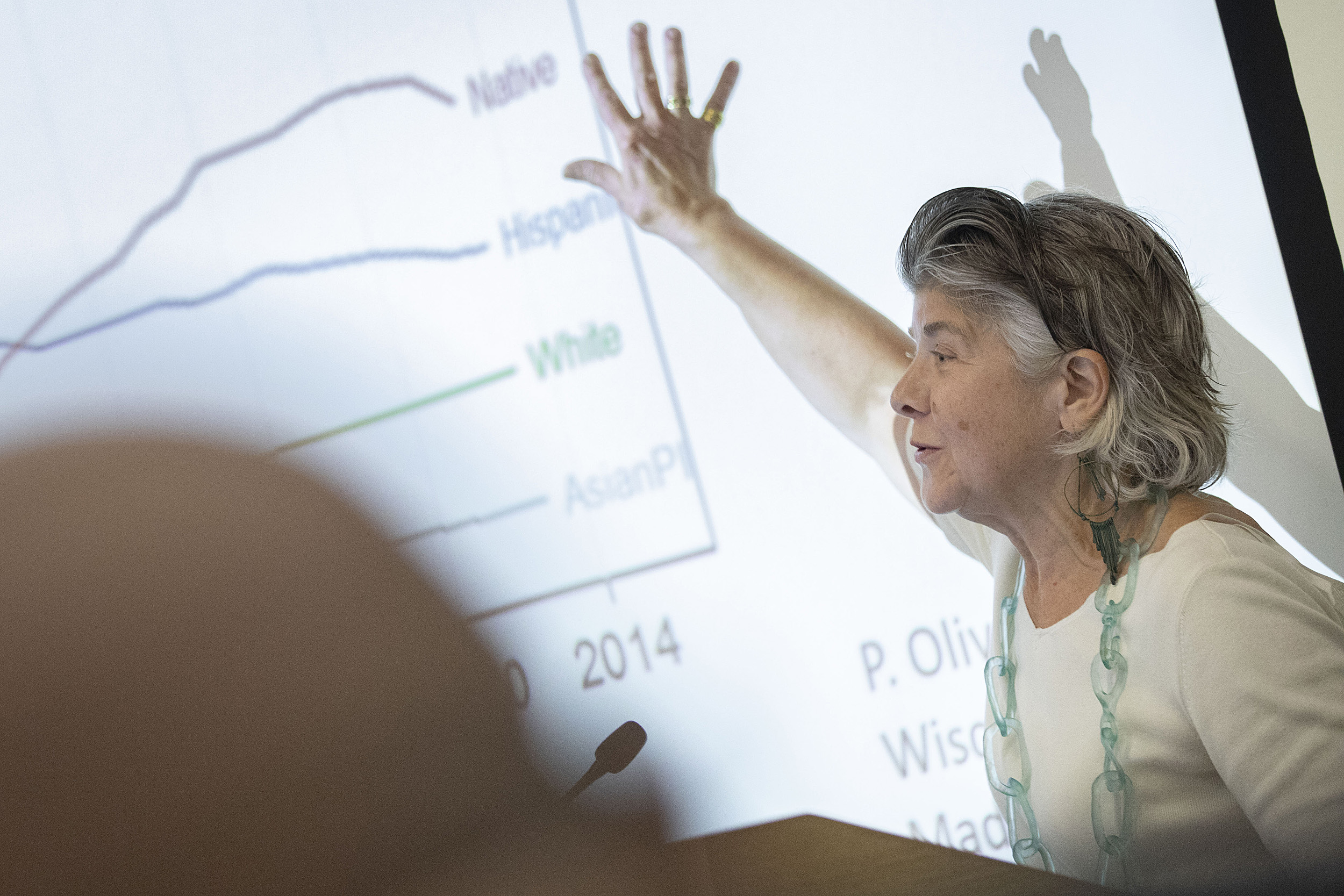

Evelynn Hammonds

Barbara Gutmann Rosenkrantz Professor of the History of Science and professor of African and African American studies

GAZETTE: What should we take away from the election overall?

Hammonds: This has been one of the most tumultuous elections in U.S. history. Frankly, if Biden/[Kamala]Harris do not win then I believe we will be facing a very dark period in this country for at least two reasons. First, because of the disdain for science and expertise by the Trump administration which has exacerbated the impact of the coronavirus throughout the country. Hundreds of thousands of people are dying, many of them needlessly, because of the administration’s blatant disregard of the best scientific practices. This is unconscionable by any measure. As a result, it will take an enormous effort to end this pandemic.

Secondly, this disdain for science is coupled with explicit racism from this administration. Trump has made it clear that the suffering of Black and brown people means little to him. Whether Trump wins or not, this is a moment when those of us who have been fighting to end health disparities in America that have been revealed by the coronavirus pandemic will have to redouble our efforts to end inequalities in health care and all areas of American society. This election is a serious call to action for those who believe in American democracy.

Kris Snibbe/Harvard file photo

Harvard University

Carol Steiker

Henry J. Friendly Professor of Law

GAZETTE: What should we take away from the election overall?

Steiker: What I have learned in this election is that despite, or perhaps because of, the anger and divisiveness that have marked this political season, it is possible to substantially shift the needle on popular political engagement. We are seeing levels of voter turnout in this election not seen in more than a century, since William Howard Taft defeated William Jennings Bryan in 1908.

If polls are accurate and Joe Biden wins the presidency, there will undoubtedly be a shift in federal criminal-justice priorities. I would expect to see some changes in federal prosecution policies on issues like the death penalty and mandatory minimum charges, as well as legislative initiatives on issues like the decriminalization of marijuana and further reduction of the racially tilted crack/powder sentencing disparities, as Biden has highlighted in his campaign. A Biden Justice Department would no doubt seek to use its authority to influence state criminal justice policies as well, both by carrots (federal grants) and sticks (Justice Department investigations and consent decrees to address systemic police misconduct, as the Obama Justice Department did in Ferguson, Mo.). However, history has shown that differences between Democratic and Republican administrations on criminal justice tend to be modest, so I would not expect to see any full-throated endorsement of the radical changes in policing and punishment practices that many protesters have been calling for around the country. Moreover, in the United States, a substantial amount of regulation of the criminal justice system is done through constitutional interpretation by the federal courts — an area in which Trump’s influence will far outlast his presidency.

Photo by Lorin Granger/Harvard Law School

Lorin Granger/Harvard Law School

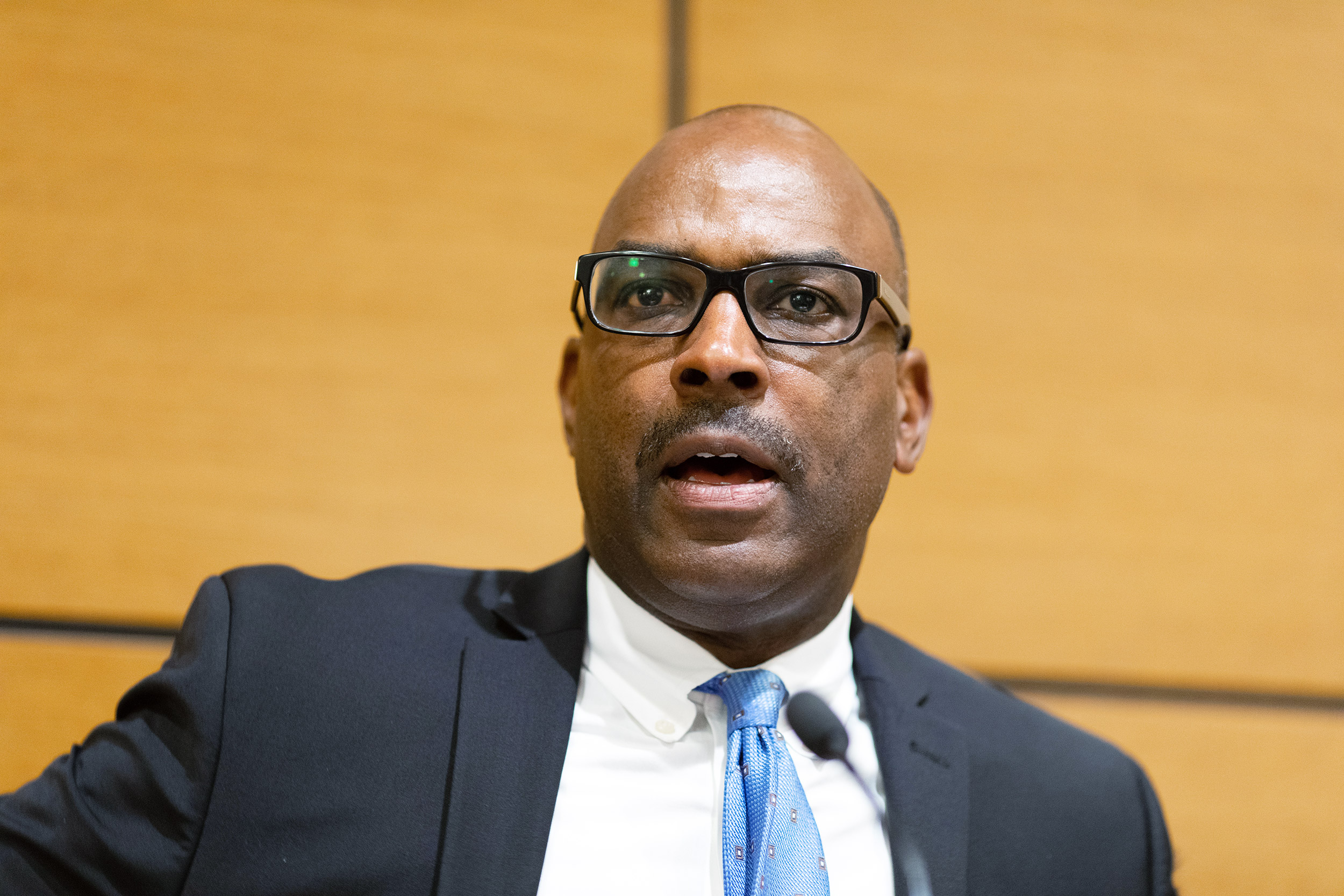

Kenneth Mack

Lawrence D. Biele Professor of Law

GAZETTE: What should we take away from the election overall?

Mack: What I have learned from this election so far is both a lot and a little. Historians typically look at elections as vehicles for possible political, economic, or social change. Certainly in the run-up to this year’s election we’ve seen some things change significantly. We have the first woman of color on a major party ticket (who now seems poised to become vice president), Black candidates seeming to run competitively statewide in several Southern states, and efforts to suppress minority voting of a kind we haven’t seen in decades.

We also have a national social movement to counter structural racism that has found support rather than backlash in many suburban areas. We have policies being debated, surrounding a range of issues — from policing to measures to combat economic inequality and to support the environment — that would have not garnered significant support 10 years ago. At the same time, the coalition that elected and supported Donald Trump as president shows many cracks but remains intact, and the visions of everything from court-packing to a Green New Deal that animated discussions within the Democratic Party are off the table for the immediate future. Also endangered is the prospect of undoing the process of packing the judiciary with Trump nominees. We’ve also seen that the erosion and endangerment of democratic norms that has occurred in the past four years continues apace, as exemplified by the president’s false claims of victory on election night and his public entreaties that his opponents’ votes not be counted as they are required to be under existing law. With continued efforts to contest legitimate legal processes for counting votes and continued efforts to delegitimize election results, the process of norm-erosion may in fact be augmented rather than dissipated by Biden and Harris’ probable victory. Much was at stake in this year’s elections, and it matters a great deal who won them for many important policies, such as climate change and public health. The evidence we have so far, however, would counsel caution about the predictions, so prevalent only days ago, that the November elections would produce substantial, longer-term change.

By definition, the struggle for racial justice in the United States is a long one, with very few national elections as true inflection points or moments where something historic has been decided. Certain elections do constitute such points — 1876, 1948, 1964, 1968, 1980, and 2008, for instance — while most are not. Certainly in the run-up to this election, we’ve seen an unprecedented number of people participate in antiracist protests, and we’ve seen a new set of reforms focusing on prisons and policing garner a far wider range of supporters than anyone would have predicted 10 years ago.

We also saw a reopening of battles for racial minority access to the ballot that were thought settled long ago, prompted by the Supreme Court’s invalidation of a portion of the Voting Rights Act. We saw candidates in the Democratic presidential primaries embrace issues such as bail and prison reform, curtailing private prisons, felon enfranchisement, ending mandatory minimums, and other measures that emerged from social movement pressure.

At the same time, the specific results of the November elections, as we know them so far, don’t seem to coincide with a strong mandate for racial-justice policies beyond the ones that already have bipartisan support, such as significantly reducing the prison population among nonviolent drug offenders. It may be that future generations will see this election as a turning point of sorts, but the initial evidence we have indicates that the specific results of the November elections mark a continuation of existing debates rather than a sharp differentiation from what has come before. Nonetheless, that shouldn’t distract from the proposition that 2020 has been a historic year in which racial justice movements have gone mainstream in service of the project of making our democracy work for everyone.

Jon Chase/Harvard file photo

Harvard University News Office

Yochai Benkler

Jack N. and Lillian R. Berkman Professor for Entrepreneurial Legal Studies

GAZETTE: How instrumental were right-wing information networks in this election as compared to 2016, and why?

Benkler: The right-wing propaganda feedback loop, anchored in Fox News and talk radio and supported by online media, has played two critical roles in the election. The first, and most foundational, is that throughout the presidency of Donald Trump it offered an alternative reality, in which the president was a strong, effective leader hounded by an alliance of Democrats who hate America and Deep State operatives bent on reversing the victory of Trump, the authentic voice of the people. In this universe, COVID-19 was not an unusual or particularly dangerous condition but an overhyped threat intended by elites to besmirch Trump. Only on the background of this separate epistemic existence can Trump’s unwavering support in the teeth of the pandemic and its economic consequences be understood.

The second role that disinformation played and is now continuing to play in the postelection tussle is as the source of legitimacy for an institutional rear-guard battle. This is happening most clearly in Pennsylvania, where the Republican-controlled legislature used the false narrative about mail-in voter fraud to defend provisions prohibiting early processing of mail-in ballots. The only logical purpose of such an intentional administrative hobble is to delay the counting of mail-in ballots, which, because of the propaganda aimed to reduce fear of COVID, was predicted by all to be used more broadly by Democrats. That delay in counting mail-in ballots predictably led to the confusion we see at present and is again supported from the first moments after midnight as Trump’s claim that counting the mail-in ballots is an effort to steal the election.

Justice Brett Kavanaugh, in turn, in his opinion in the Wisconsin case suggested a path for a Republican-stacked federal judiciary to step in and take over from duly elected state executive-branch officials and state courts to enforce the wishes of thoroughly gerrymandered state legislatures. What we are seeing in Pennsylvania is a quintessential campaign that combines disinformation with institutional hardball leveraging narrow points of anti-majoritarian control to maintain that control in the hands of an ever-shrinking minority of white identity voters and religious fundamentalists.

Jon Chase/Harvard file photo

Jon Chase/Harvard Staff Photogra

Alejandro de la Fuente

Robert Woods Bliss Professor of Latin American History and Economics, Professor of African and African American Studies and of History, and Director of Afro-Latin American Research Institute

GAZETTE: Were you surprised by the Cuban American vote in Florida?

De La Fuente: It did not come as a surprise. Although Democrats were hoping to reproduce or even expand their traditional lead in Miami-Dade County, it was expected that Cuban Americans, who represent over one-third of the population of the county, would support President Trump by wide margins. Whereas former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton won the county by almost 30 points in 2016, Vice President Joe Biden’s lead was reportedly under 10 percentage points.

It would be tempting to read this result as a consequence of the policy changes that the current administration has pursued concerning Cuba. That does not seem to be the case. At least not directly. As Guillermo Grenier, a sociologist at Florida International University who conducts the most authoritative poll on Cuban American political preferences, explained at a recent seminar [hosted by Harvard’s David Rockefeller Center for Latin American Studies], other issues are more important to them. These include mainstream issues such as the economy, health care, immigration, and public safety. Cuba is not at the top of the list. On these issues, many Cuban Americans vote similarly to white working-class Americans.

Although some analysts lump Cuban Americans with other Latino groups, this association says more about the American gaze than about understandings of race, ancestry, and culture among Cubans. Most Cuban Americans self-identify as white and approach electoral issues as white voters. Their ethnic enclave provides a sheltered space for the reproduction of traditional understandings of whiteness, class, and racial difference. Treating “Latinos” as a voting bloc obscures other regional, cultural, and generational differences that shape how they vote.

Not that Cuba does not matter at all. The current administration has systematically courted Cuban Americans and other Latin American immigrants, especially Venezuelans, by adopting sanctions against the governments of Cuba and Venezuela. If there is something that unites Cubans across political preferences and generations, it is the need for change in the island. At the same time, Republicans have relentlessly and successfully portrayed Democrats as “socialists,” as soft on “communism,” and as friendly to Latin American dictators such as Nicolás Maduro. The irony of such charges notwithstanding, coming from a president who has been openly sympathetic to authoritarian rulers the world over, they seem to have worked.

Maria Barsallo Lynch

Executive Director, Defending Digital Democracy Project at Harvard Kennedy School’s Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs

GAZETTE: What did the election reveal about the integrity of U.S. elections?

Barsallo Lynch: As a bipartisan security project, since 2017 the Defending Digital Democracy Project (D3P) has been working with decision-makers in the democratic process to provide actionable recommendations to counter cyber and information threats targeting elections.

Over this past year alone, D3P has engaged close to 900 election officials around the country assessing the evolving threat landscape to elections and working to counter cyber and information threats like the ones we’ve seen reported throughout this election cycle.

As Americans exercised their fundamental right to vote in this election, we know that malicious actors were seeking to disrupt and interfere in the election. As a project, we also know there are so many Americans, individuals, organizations, agencies, working across sectors, to counter those efforts and maintain the integrity of the election.

The historic turnout shows that, despite hostile efforts to create doubt around our democratic process, Americans’ confidence in our democracy — and our commitment to exercising our right to vote — was not undermined by these attacks. There will still be more to learn about these threats and tactics as results come in and after the election is over.

Results are taking longer to report — that is OK and expected. This is an unprecedented election. The significant operational challenges associated with holding an election during a pandemic — especially an enormous increase in voting by mail — affect the usual pace of election night. D3P created the Election Data Set to help media and voters get a sense of these elements that may factor into the results-reporting period.

Maintaining the integrity of the election means making sure every vote is counted. This is understandably taking longer this year. Given such a change from what we’re used to, the potential for confusion may be high and that confusion may still be exploited to create doubt in the integrity of process.

— Manisha Aggarwal-Schifellite, Liz Mineo, Christina Pazzanese, Alvin Powell, Juan Siliezar, and Colleen Walsh contributed to this report.

Responses were gently edited for clarity and length.