Creating art from Radcliffe archives

Tomashi Jackson draws on images from Schlesinger Library for pieces inspired by Brown v. Board of Education

In her latest exhibit, “Brown II,” artist Tomashi Jackson highlights the struggle for educational equity. In the spring, Jackson will return as visiting lecturer in Harvard’s Art, Film, and Visual Studies.

Photo by © Jessica Dalene/Courtesy of The Watermill Center

For Tomashi Jackson, engaging with history is an artistic endeavor.

The history of school desegregation became a focus of the artist’s gaze in 2014 (and of her recent campus show) as she watched activists fight to halt a plan to eliminate buses for Boston Public School seventh- and eighth-graders, replacing them with subway and bus passes. Parents who had concerns about their 12- and 13-year-olds’ safety on public transportation said it might limit their school choices to only those to which their children could walk.

“I just remember thinking this sounds like a pre-Brown v. the Board of Education era” debate about racial and economic barriers to opportunity, Jackson said during a recent phone interview.

As she began documenting the hearings with her camera, Jackson, who will be a visiting lecturer in Art, Film, and Visual Studies in spring, also began realizing how unfamiliar she was with the five “transformative” school desegregation cases collectively known as Brown v. Board of Education, and their impact on both history and her own life. Brown was launched by Oliver Brown, angered because his daughter was not allowed to attend a school near their home and was instead to be bused to a “separate but equal” one farther away.

Jackson said it never occurred to her that the daily bus trip she took as a girl to her high-quality magnet school on the University of Southern California campus was rooted in a fierce struggle for educational equity.

Radcliffe Dean Tomiko Brown-Nagin (from left) and artist Tomashi Jackson discuss the inspiration behind Jackson’s new exhibit “Brown II.”

Rose Linoln/Harvard Staff Photographer

“It was like all the wind was knocked out of me. I thought, ‘Wow, this is just daunting … there’s so little that I know, and I am a direct beneficiary of these policies.’”

So she went back to school herself, poring over the Brown court transcripts in the Yale Law Library while studying painting and printmaking in the university’s master of fine arts program. That archival research informed her first solo show in New York in 2016, an interrogation of “the subliminal impact of color perception on the value of human life in public space” reads a gallery description of the exhibit.

Two years later, when Radcliffe administrators invited her to create an exhibit, Jackson jumped at the opportunity to tap into the Institute’s vast resources and build on that earlier body of work.

“I immediately thought, ‘This is my chance to return to the Brown research,’” said Jackson, “because I’ve barely scratched the surface.”

Now that new work is ready to view. “Brown II,” on display in Byerly Hall’s Johnson-Kulukundis Family Gallery, features four evocative paintings based on images from the Schlesinger Library’s archives of Civil Rights activists Pauli Murray and Ruth Batson, two key figures in the fight for public school desegregation. In addition Jackson has on display in the Yard vibrant banners honoring the pair, which will remain up through Thanksgiving. Murray “helped to craft the legal theory that the NAACP relied on during the 1950s to win Brown,” and Batson, a Roxbury native, “was a leader in the struggle to desegregate the Boston schools” in the decades that followed, said Radcliffe Dean Tomiko Brown-Nagin during a virtual discussion with the artist last Monday.

“They are the keys to this history, to what happened,” Jackson replied.

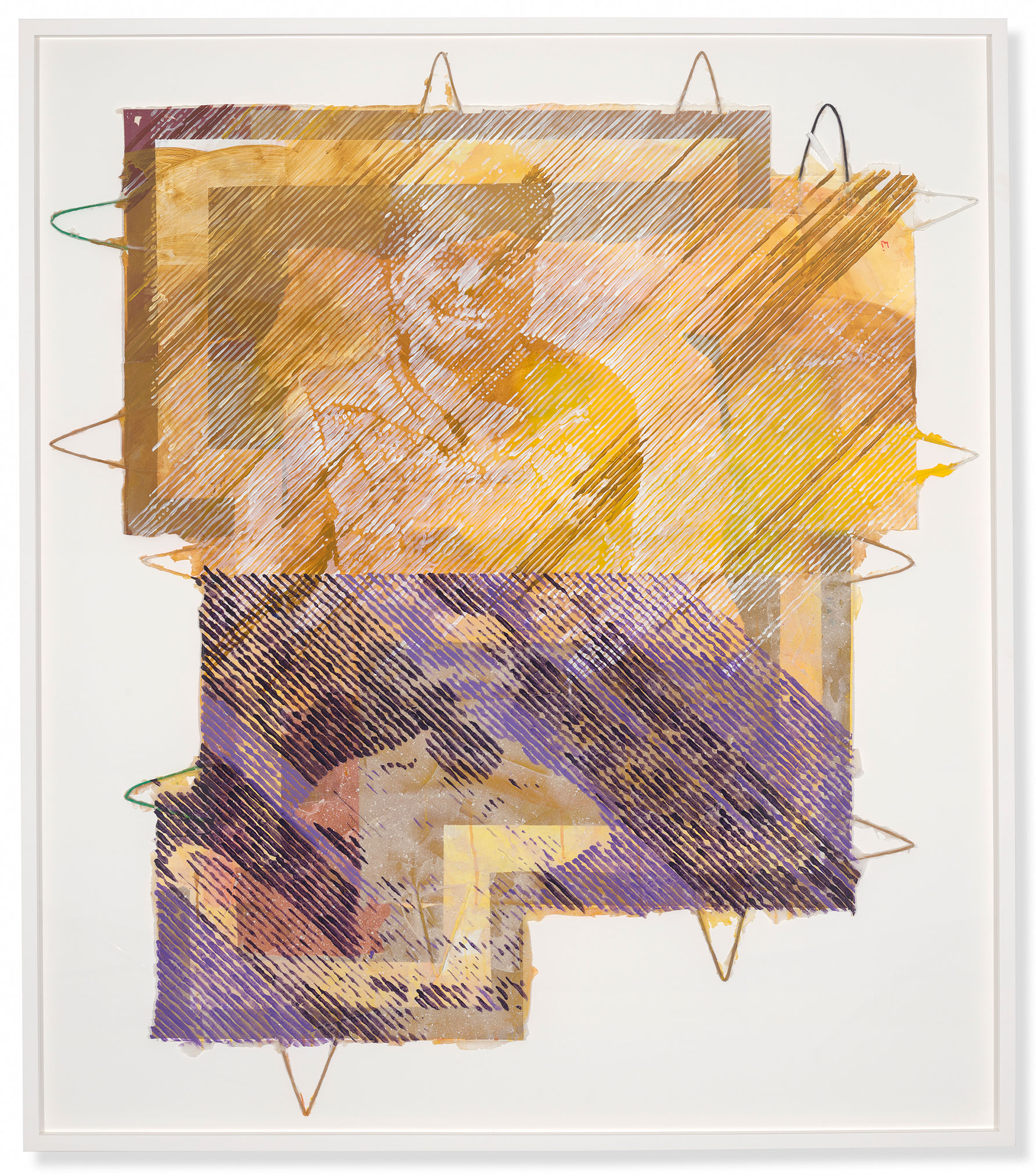

“The Makings of You” (Ruth in Gold/ Pauli in Violet), 2021. Acrylic on pentelic marble dust and paper bags laminated into archival cotton paper.

Image courtesy of Tomashi Jackson and the Tilton Gallery

Brown-Nagin praised Jackson for the way her work embraces the idea that “social change occurs along an historical continuum, instead of in a singular, triumphant moment,” like the Brown ruling. “It’s terrific, that you have managed to express that concept through your work,” said Brown-Nagin, “and also join the past to the present.”

But in the age of COVID, no process is ever simple. When the pandemic sent the Harvard Radcliffe Institute into lockdown in the spring of 2020, Jackson’s exhibition was put on hold. The artist was undaunted. With help from the Institute, she connected with three Harvard graduate students, and together they merged the creative with the academic. Their resulting effort, a 50-page publication based on interviews with a range of scholars from Harvard and beyond, offers readers a further look at history from a range of perspectives, and at the repercussions of the various Brown decisions.

“It’s just it ended up being this incredible experience and this incredible document that I wanted to be accessible as a curricular reference for the future,” said Jackson.

The book, a blend of art and commentary, contains 10 essays, including contributions from David Harris, managing director emeritus of the Charles Hamilton Houston Institute for Race & Justice at Harvard Law School, on the history of school desegregation efforts in Boston, and from Brown-Nagin on the legacy and leadership of activists Ida B. Wells, Murray, Constance Baker Motley, and Batson. Accompanying each entry are images by Jackson, archival photos, and a series of sketches by Martha Schnee, Ed.M. ’20, that lend the book added nuance and depth.

“It just beautifully fits within Radcliffe’s hopes for what the visual arts can bring and do within academia,” said Meg Rotzel, curator of exhibitions at Harvard Radcliffe Institute, who helped coordinate the new show.

Jackson had considered creating works for the show in New York and then shipping them to Cambridge. Instead, she turned a small space on Radcliffe’s campus into a makeshift studio during the lockdown, and painted there from March through May. “I had a place to go work that was steps away from the apartment that I could walk to safely,” said Jackson. It felt like “a timely miracle.”

“Brown II” will be on display through Jan. 15, 2022, at the Johnson-Kulukundis Family Gallery in Byerly Hall. Harvard University ID holders can make an appointment to visit the show through the month of September. In October, the gallery will be opened to the public with timed ticketing.