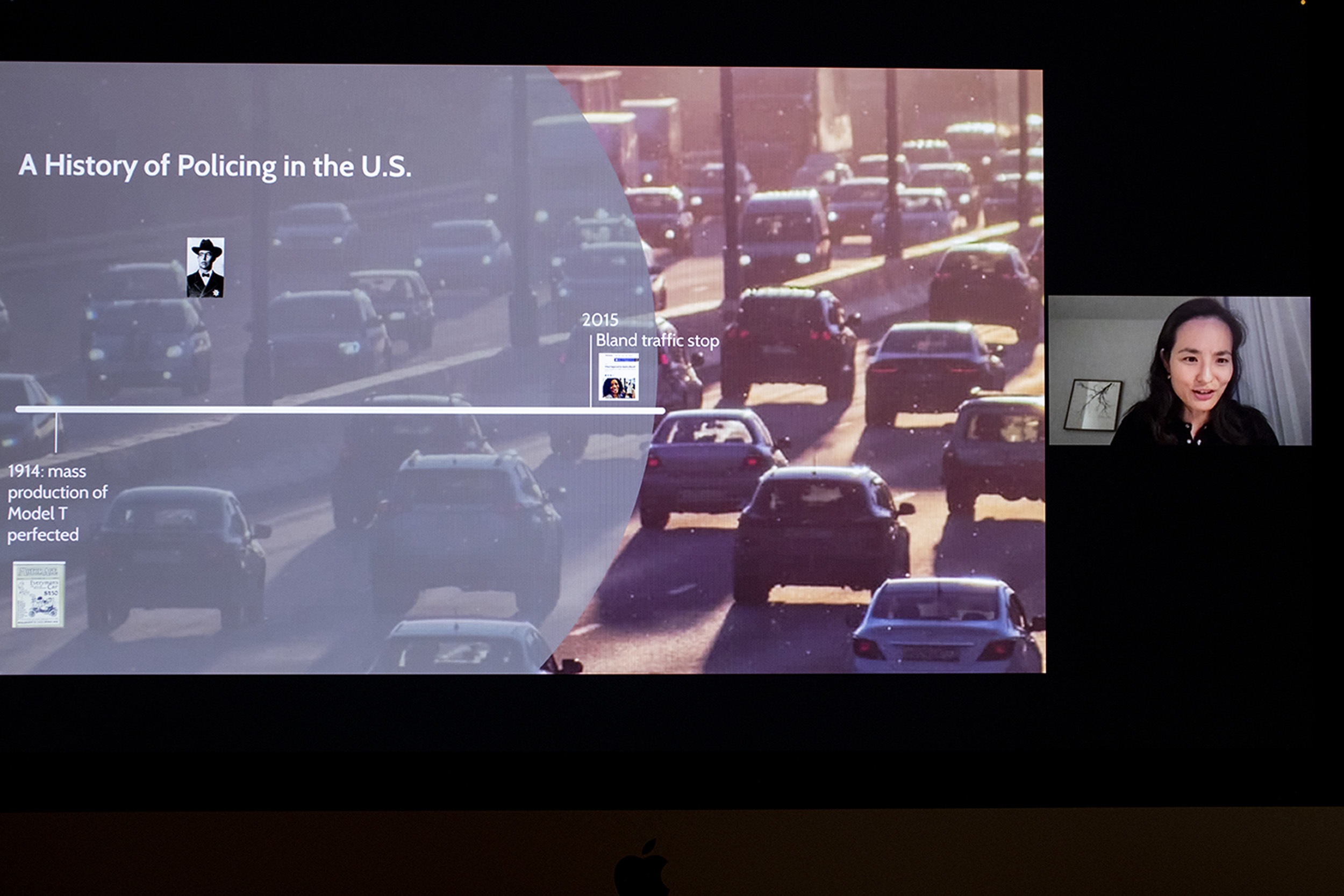

The history of cars and policing are deeply connected, says Sarah Seo, who suggested reassigning the enforcement of traffic laws to a non-police agency.

Rose Lincoln/Harvard Staff Photographer

Legal historian traces ‘racism on the road’

Sarah Seo calls for removing police from traffic law enforcement, citing recent events, long history of officers’ bias

Calls to remove police from traffic enforcement have increased following numerous killings of Black motorists by officers over minor traffic violations in the past few years. Last month, citing racial disparities in traffic stops, Philadelphia became the first major U.S. city to ban officers from stopping drivers for such offenses.

But the police racial-profiling practice, sardonically referred to as Driving While Black, has a long history, said Sarah A. Seo, a historian of criminal law and procedure in the 20th-century U.S., at a speaker series last week at the Harvard Kennedy School’s Malcolm Wiener Center for Social Policy.

Seo, who wrote the book “Policing the Open Road: How Cars Transformed American Freedom,” traces the first incidents of police abuse of Black drivers to the early 1930s. While researching the archives of the NAACP, the Columbia Law School professor found letters from the period written by Black citizens complaining about discrimination in traffic policing.

One of the most notorious cases in the ’30s involved a Black teenager named Stanley Jackson, who worked at a gas station in Perth Amboy, N.J., and decided to take a car that had been serviced for a ride. He was pulled over by a state trooper who suspected the teen of stealing the car and shot him. Jackson spent a month in the hospital and was charged with resisting an officer and reckless driving.

The potential perils of traveling longer distances by car were so well known in the Black community that a Harlem postal carrier published “The Green Book” in 1936. The book was intended as a guide to help Blacks negotiate unfamiliar new areas where they could face inconveniences and potential dangers, from refusal of various kinds of services to police hostility.

“As soon as Black people began driving, they experienced not just discourteous, but also abusive, violent, and unconstitutional policing,” said Seo. “Racism on the road became even more entrenched when traffic violations were used to pursue criminal investigation.”

While the traffic stop is still the most common encounter between individuals and the police, drivers of color tend to be overpoliced, said Seo. A study by the Stanford Open Policing Project found that Blacks are 20 percent likelier to get pulled over than whites.

“As soon as Black people began driving, they experienced not just discourteous, but also abusive, violent, and unconstitutional policing.”

Sarah A. Seo

The history of cars and policing are deeply connected, said Seo. In her book, she writes that the mass production of cars, and the traffic safety issues that ensued, led to the professionalization of the police. In the early 20th century, traffic norms were enforced via the honor system and through voluntary and civic associations, but when traffic safety became too big an issue to be left to self-governance, police were given the task of overseeing traffic law enforcement.

Given the surge in reports of violent encounters between police and Black drivers, Seo supports reassigning responsibility for enforcing traffic laws to a non-police agency. Having police enforce traffic laws has led to abuse and undermined public safety on the road, she said.

The idea of removing traffic enforcement from the police is not new, said Seo. August Vollmer, considered the father of modern law enforcement, opposed having police oversee traffic laws. Vollmer was police chief of Berkeley, Calif., between 1909 and 1923.

“He was not a fan of having the police enforce traffic laws because he thought it would distract them from its main duty of fighting crime,” said Seo. “Separating traffic law enforcement and criminal law enforcement would undo the history of abuse that arose from the merger of these two functions.”

When thinking about possible reforms, Seo said that policymakers should consider banning police from making investigatory stops, which officers do when they have reasonable suspicion a crime has been committed. The stops are both ineffective at fighting crime and counterproductive to safety, she said, but more significantly, they’re applied disproportionately against people of color.

“Perhaps, investigatory stops would be fine if we all experienced it,” said Seo. “More likely, if every man experienced that kind of policing, it wouldn’t be allowed anymore.”

Investigatory stops also create a tense, unpredictable, and uncertain situation where everyone involved experiences fear, and things can quickly escalate and lead to violence, said Seo.

“Drivers of color are scared of being pulled over,” said Seo. “Police officers say that’s one of the most dangerous tasks. We are doing something very wrong when everyone’s feeling scared or anxious about something that’s not supposed to be inherently dangerous.”

Another possible solution is automated traffic enforcement, such as speed cameras, which could eliminate police discretionary power and increase public safety by minimizing encounters between civilians and police. Seo said technology could be used for speeding, running red lights, or checking car registrations or expired drivers’ licenses, but along with it there must be privacy protections.

Seo recommended a well-rounded approach when considering reforms.

“From thinking about what more can be done, it’s important to consider history lessons,” she said. “It’s also important to consider something as mundane as traffic enforcement from an equity perspective and to include the perspective of those who bear the brunt of discretionary policing.