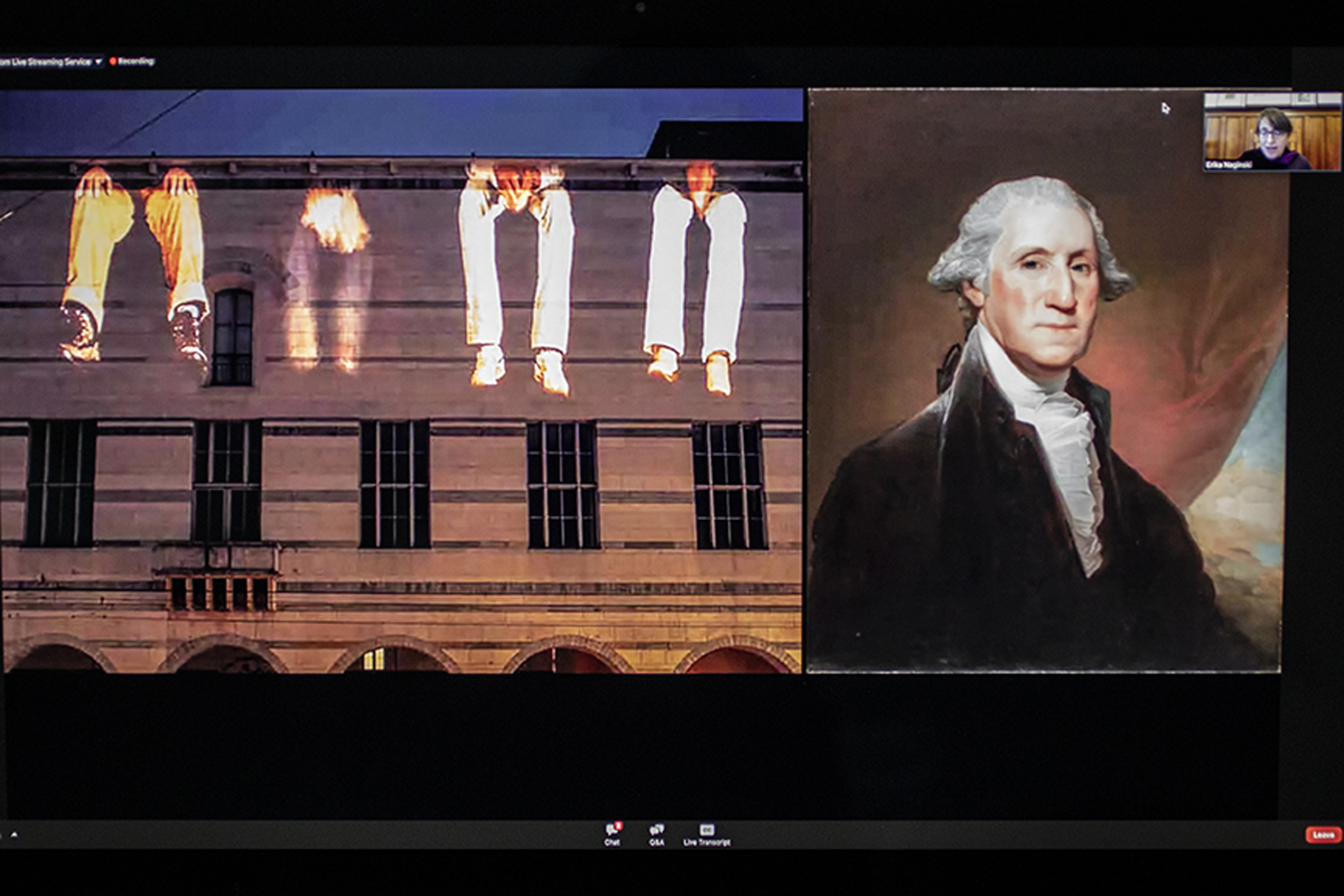

Krzysztof Wodiczko’s “Sans-Papiers,” 2006, Basel Switzerland, pictured alongside his latest project, the animation of the Gilbert Stuart portrait of George Washington, featured at Harvard Art Museums.

Rose Lincoln/Harvard Staff Photographer

Bringing monuments to life

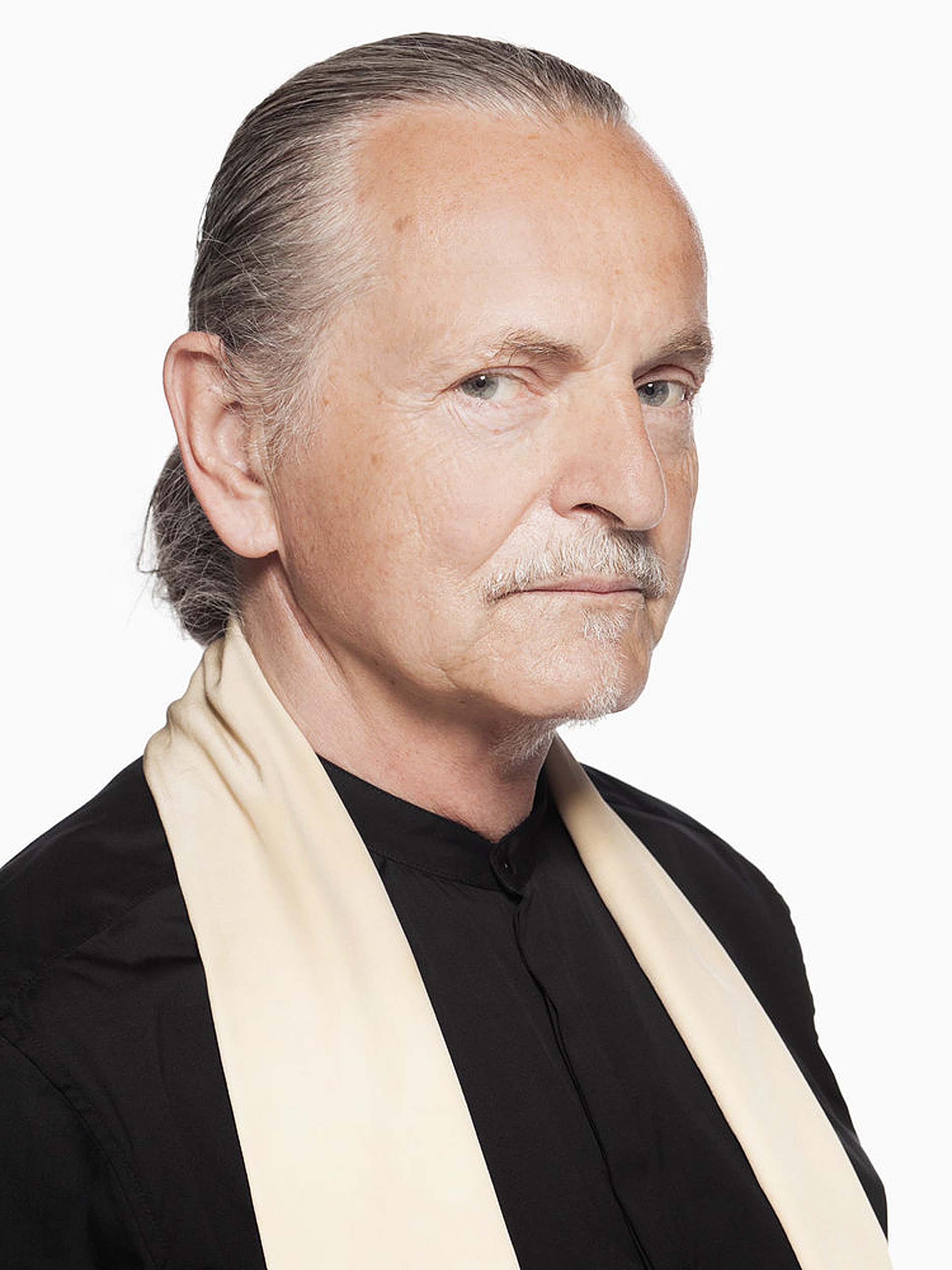

Conceptual artist Krzysztof Wodiczko aims to give voice to the voiceless through his projections on buildings, statues

For much of the past 40 years Krzysztof Wodiczko has made famous monuments come alive to amplify the hopes and fears of real people. On Friday the conceptual artist discussed the creative impulse behind his work during a pair of talks sponsored by the Graduate School of Design.

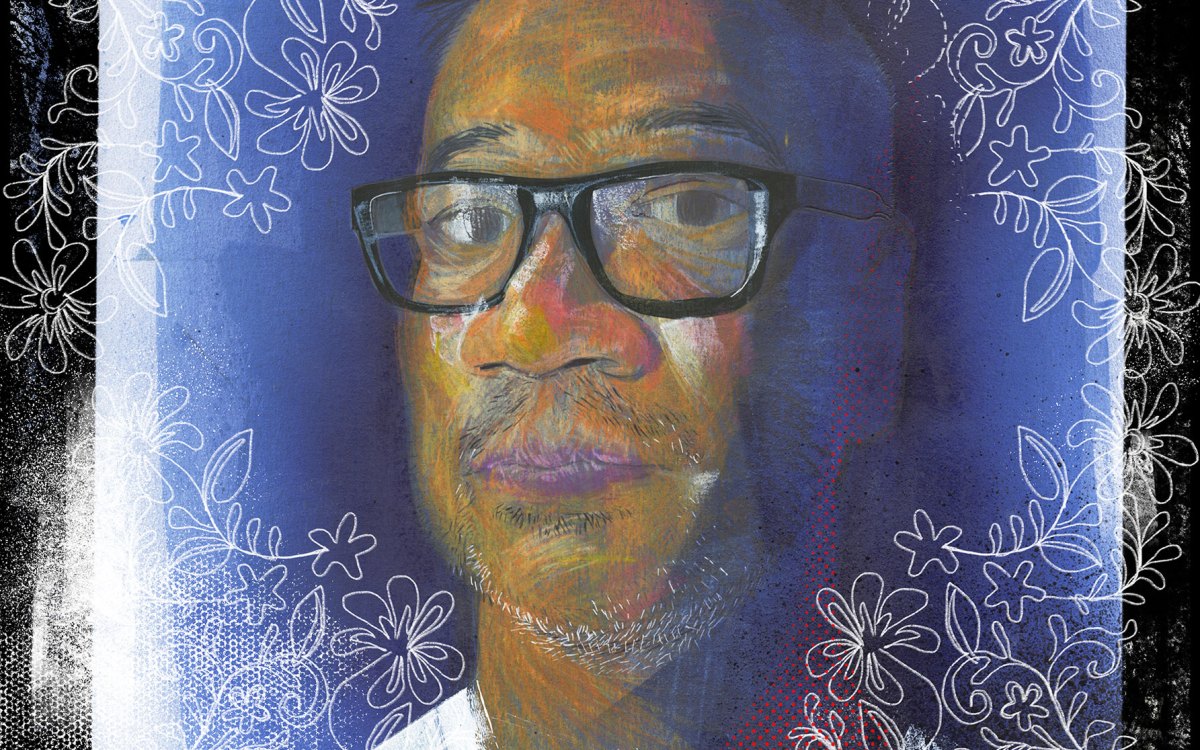

For Wodiczko, professor in residence of art, design, and the public domain at the GSD, the drive to enliven statues, building façades, and famous faces is rooted in his desire to give voice to the most marginalized in society and those who often feel unable to speak freely in city squares, parks, or commons, places designed for open discourse.

“Public space is a space of rights,” he said, adding that priority to speak in such places should be awarded to those who see the world from the bottom up rather than from the top down. “The very well-being of democratic process depends primarily on those peoples’ capacity for open speech and public expression. They should be the first to receive the opportunity … to communicate the truth of their lives.”

Born in Poland during the 1943 Warsaw ghetto uprising, Wodiczko initially rejected the title of artist, referring to himself instead as a designer. The moniker seemed to fit. He received his degree in industrial design from the Academy of Fine Arts in Warsaw in 1968 and spent the first part of his career designing electrical products and optical instruments. But his attitude quickly began to shift with one of his early artistic creations, “Personal Instrument,” a wearable work consisting of a microphone and gloves fitted with receivers, which filtered and transmitted sounds to a set of headphones. Created in 1969, Wodiczko said the piece represented the selective listening required of Polish citizens living under a communist regime.

“It seemed to be response to the situation that should not exist in a civilized world, not definitely a democratic world, or in public space, period,” he said. “It was a situation in which we were not allowed to speak much, only listen.”

The online events coincided with new exhibit titled “Interrogative Design: Selected Works of Krzysztof Wodiczko” on view at the School of Design through February (but temporarily only open to Harvard ID holders) and a new projection installation at the Harvard Art Museums now open to the public. The museum exhibit “Krzysztof Wodiczko: Portrait” uses the voices and images of students and young people from Harvard and the Boston area to animate the famous Gilbert Stuart portrait of George Washington around questions of democracy. The new work, installed in a black-box gallery on the museums’ ground floor, is on view through April 17.

Listening to and elevating the stories of those whose lives have been marked by poverty, abuse, homelessness, immigration, and more has been a driving force behind much of Wodiczko’s output since the 1980s, when he first began animating large architectural façades and monuments with projected images.

One of his projects involved Boston’s Bunker Hill Monument. He illuminated the Revolutionary War memorial in 1998 with the images and voices of mothers whose children had been murdered in the surrounding neighborhood, which had become infamous for its high rate of unsolved killings owing to a code of silence among residents. In 2012 he animated the Abraham Lincoln statue in New York City’s Union Square, which had been commissioned not long after the end of the Civil War and Lincoln’s assassination, with the voices of veterans who discussed the trauma of war.

“Public space is a space of rights. The very well-being of democratic process depends primarily on those peoples’ capacity for open speech and public expression.”

Krzysztof Wodiczko

In 2015, he turned the John Harvard statue into his canvas, superimposing the faces and voices of students on the seated figure. The work, he said then, gave students from across the University the opportunity to express themselves. Most recently, he layered the likenesses and narratives of refugees resettled in the United States on the 1881 statue of Civil War leader Admiral David Glasgow Farragut in New York City’s Madison Square Park.

His current installation at the Harvard Art Museums was inspired by the deepening political polarization in the U.S. and beyond. The artist interviewed a number of students and community members about the state of democracy and projected their responses on the images of three reproductions of the famous painting of George Washington. While one speaks, the others appear to listen. The exhibit highlights both Wodiczko’s artistic ethos, and his embrace of ever-changing technology.

In his Friday remarks, the artist outlined how his work has evolved through the years from the use of basic slide projections to more sophisticated video and film displays. Today he relies on cutting-edge mapping software that enables him to graph the faces of his participants onto the statues or portraits he brings to life. In recent years he has begun using drones as part of his work and he said he could see using holograms in his future projects.

“This might be a natural step … I am thinking of doing it,” he said.