Rocky path to publication for ‘most dangerous book’

Judged ‘vile’ and ‘obscene’ in 1922, Joyce’s ‘Ulysses’ exploded old ways of thinking about fiction — and world itself

Courtesy of Penguin Books

Excerpted from Kevin Birmingham’s “The Most Dangerous Book: The Battle for James Joyce’s ‘Ulysses’” (2014) , courtesy of Penguin Books.

Sylvia Beach’s offer happened casually, as if they had been preparing themselves since they shook hands in André Spire’s library and now all they needed to do to launch the ship was to break the bottle. Joyce, disconsolate, went to Shakespeare and Company and told Miss Beach about the obscenity conviction against The Little Review in New York for publishing the “Nausicaa” episode of “Ulysses.” “My book will never come out now,” he said. Her question, when she asked it, was an answer to Joyce’s unspoken proposal. “Would you like me to publish ‘Ulysses?’”

“I would.”

Beach had never published so much as a pamphlet. She had no experience marketing or publicizing a new book, no background with distributors or printers, no familiarity with plates or proofs or galleys. She had no capital, and she could only guess about costs and financing. Advertising would have to be based on circulars, charitable press, and word of mouth. She knew almost nothing about the legal complications of the publishing industry, in France or anywhere else, to say nothing of the complications facing a book convicted of obscenity before it was even a book. She knew the “Circe” episode was more offensive than anything in The Little Review, and she knew it would get worse.

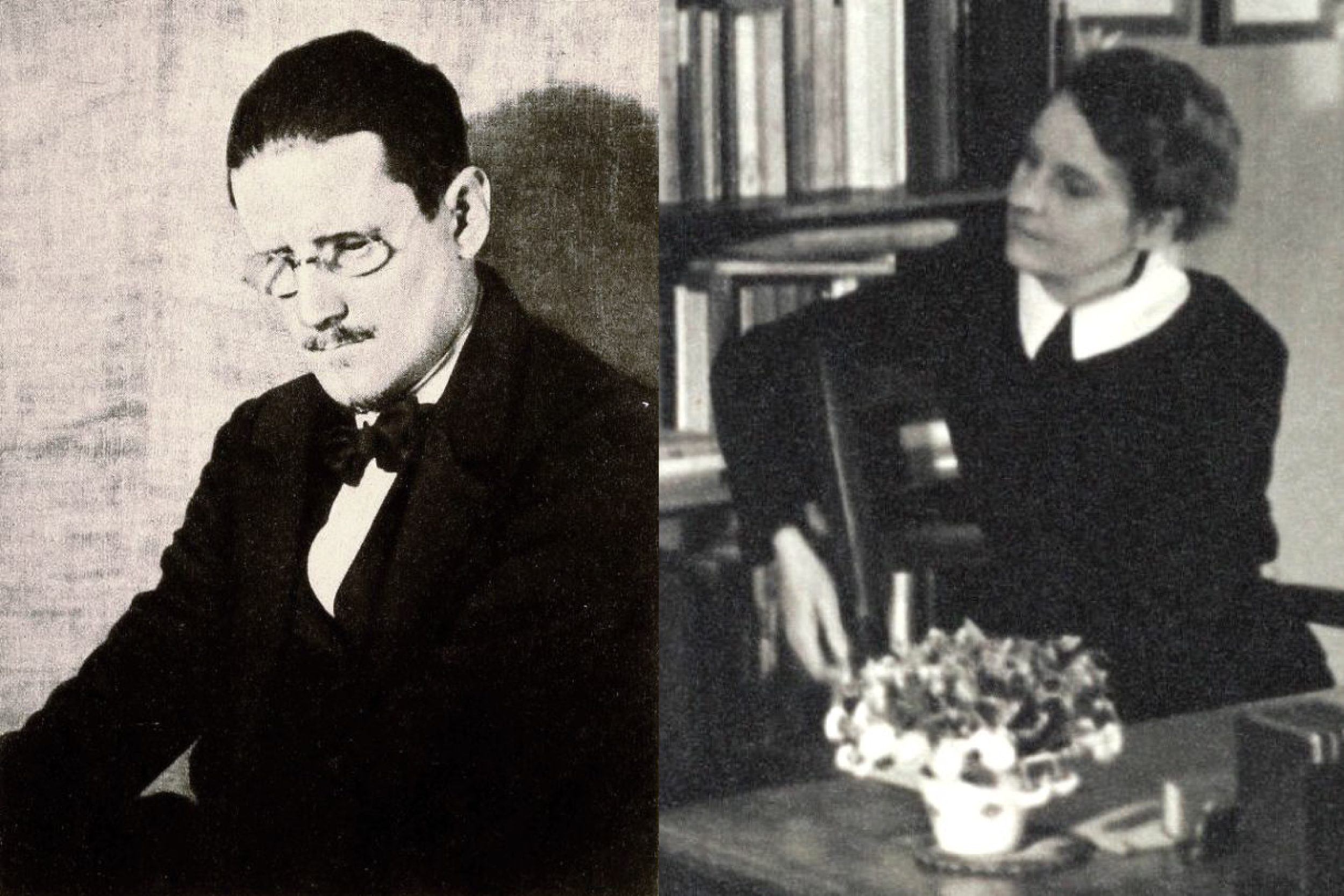

James Joyce and Sylvia Beach.

(Wikimedia Commons)

Despite all of this, she decided that Shakespeare and Company — a company of one, after all, of a 34-year-old American expatriate who was, until recently, sleeping on a cot in the back room of a diminutive bookshop on a street nobody could find — would issue the single most difficult book anyone had published in decades. It would be monstrously large, prohibitively expensive, and impossible to proofread. It was a book without a home, an Irish novel written in Trieste, Zurich, and Paris to be published in France in riddling English by a bookseller from New Jersey. Joyce’s readership was scattered. The book was at turns obscure and outrageous, its beauty and pleasures were so coy, its tenderness so hidden by erudition, that when it did not estrange its readers it provoked them. “Ulysses” was not even finished, and already it was declared obscene in New York and burned in anger in Paris.

None of this mattered. Beach wanted to be closer to Joyce and to the center of contemporary literature. She wanted to be successful and to repay the money her mother had given her. She wanted to give the world something more than pajamas and condensed milk. Beach and Joyce worked through the details themselves. Shakespeare and Company would publish a high-quality private edition of 1,000 copies. She would send out announcements and gather orders by mail before publication and pay the printer in installments as the money came in. When the book was ready, she would mail copies by registered post to readers around the world.

She borrowed Quinn’s idea of a private publication, but her prices were more ambitious. Instead of a $10 edition, Shakespeare and Company would offer three versions of varying quality. The cheapest would be 150 francs, or $12. Another set of 150 copies printed on higher-quality paper would sell for 250 francs each — $20. The premium copies would be a set of 10 books printed on Dutch handmade paper and signed by Joyce for 350 francs — $28. Even for an oversized, deluxe, private first edition, it was an extraordinary amount, the equivalent of about $400 today. The entire edition would earn $14,800, and Joyce would receive 66 percent of the profits. Neither of them thought about signing a contract.

Sylvia Beach drew up a circular announcing the plans.

ULYSSES suppressed four times during serial publication in ‘The Little Review’

will be published by ‘SHAKESPEARE AND COMPANY’ complete as written.

The circular said Joyce’s book would be 600 pages long and appear in the autumn of 1921. Beach’s sisters and friends drummed up buyers in the states. The regular patrons of Shakespeare and Company subscribed immediately and submitted the names and addresses of other likely buyers. Robert McAlmon, an American writer newly arrived in Paris, gathered orders from patrons in Paris nightclubs and dropped the order forms off on his way home in the early morning. Beach could barely make out the handwriting on some of them. Joyce showed up at Shakespeare and Company to wait for orders to arrive, and Beach recorded the names in a green notebook. Hart Crane. W.B. Yeats. Ivor Winters. William Carlos Williams. Wallace Stevens. Winston Churchill. John Quinn ordered 14 copies. And despite Josephine Bell’s arrest, The Washington Square Book Shop ordered 25 — the largest single order.

News spread quickly. Shakespeare and Company was mobbed with people, and the shop more than doubled its normal revenues. Sylvia boasted to her mother that less than two years after opening her shop, she was publishing “the most important book of the age … it’s going to make us famous rah rah!” Articles about Beach and Shakespeare and Company began to appear in the press. “American Girl Conducts Novel Bookstore Here,” The Paris Tribune announced. The article included a picture of the American Girl and reported rumors that the publication of “Ulysses” “may mean that Miss Beach will not be allowed to return to America.”

On the morning of February 2, 1922, Beach went to Gare de Lyons and waited for the Dijon-Paris express train to pull into the station. After the doors opened, she saw the conductor making his way through the harried morning travelers with a bulky parcel. Later that morning, when Joyce opened the door to his flat, Beach stood proudly in front of him with his birthday present, the first two copies of “Ulysses.”

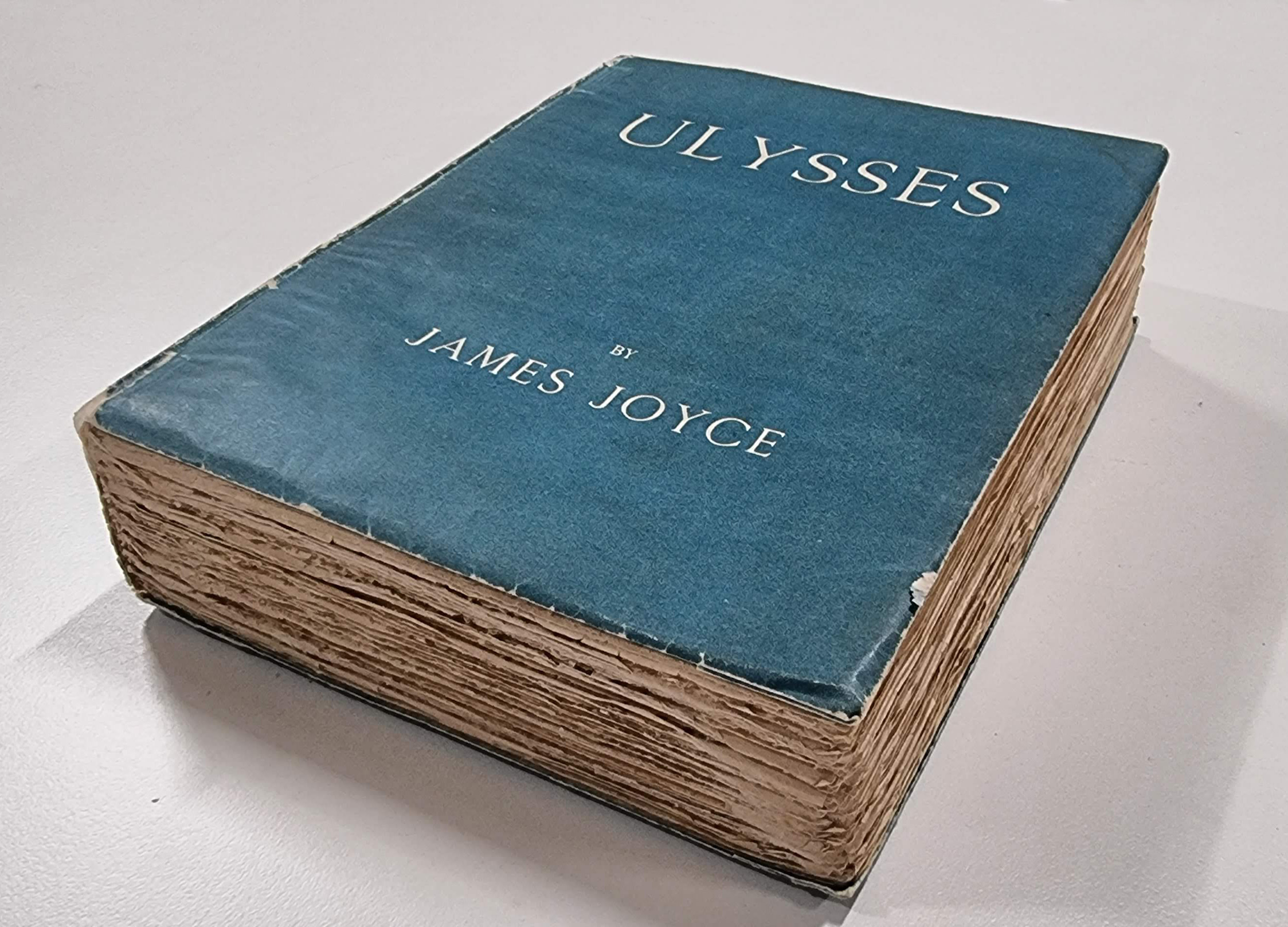

Beach placed one of the copies in the window of Shakespeare and Company. Primed by newspaper reports about the impending publication, the news spread overnight that Joyce’s “Ulysses” had arrived at last. The following morning, a crowd formed to gaze at the mighty tome in the front window. It was an imposing book: a bold blue cover, 732 pages, three inches thick and nearly three and a half pounds. People could only speculate about the rumored scenes in the final chapters. When Beach opened the shop for business, the crowd rushed in to receive its long-awaited copies. But “Ulysses,” she tried to explain, was not yet published — only two copies had been printed, but that only led everyone to claim the display copy. As they became more insistent. Beach grew afraid they were going to tear the book from its binding and divide the sections amongst themselves, so she grabbed Joyce’s novel and hid it in the back room.

As copies trickled in from Dijon in February and March, Joyce signed the 100 deluxe copies and helped Beach and others address and wrap the packages. He wanted copies mailed to his Irish readers as quickly as possible — before authorities realized they were circulating — because, he wrote to Beach, with the moralistic Vigilance Committee in Dublin and a new postmaster general “you never know from one day to the next what may occur.” In the rush, he managed to slather glue on the labels, the table, the floor and in his hair.

On Sunday, March 5, 1922, the first review of “Ulysses” appeared in the London Observer. “Mr. James Joyce is a man of genius,” Sisley Huddleston declared. The book was “the vilest, according to ordinary standards, in all literature. And yet its very obscenity is somehow beautiful and wrings the soul to pity.” Six weeks of silence followed (Joyce thought there was a boycott against him) before a review appeared in The Nation and Athenaeum that called Joyce’s quest for freedom herculean, though the reviewer had misgivings. “Ulysses” is “a prodigious self-laceration, the tearing-away from himself, by a half-demented man of genius,” J. Middleton Murry wrote. Joyce was sensitive to earthly and spiritual beauty, but the book contained too much. “Mr. Joyce has made the superhuman effort to empty the whole of his consciousness into it.” “Ulysses” had every thought a human being could have. It was bursting at the seams. Its content ravaged its form. After the tight prose of “Dubliners” and “A Portrait,” Joyce had become “the victim of his own anarchy.”

Arnold Bennett’s review the following week declared Joyce “dazzlingly original. If he does not see life whole he sees it piercingly.” The final chapter was unmatched by anything else he had ever read. “Ulysses” is not pornographic, Bennett emphasized, and yet “it is more indecent, obscene, scatological, and licentious than the majority of professedly pornographical books.” A consensus began to form as Bennett agreed that “Ulysses” was a work of genius written by an artist whose talents had gotten beyond his control. If only Joyce had harnessed his powers, Bennett lamented, “he would have stood a chance of being one of the greatest novelists that ever lived.”

The reviews could not have been better. The week after the first critic weighed in, Beach received nearly 300 new orders, including 136 orders in one day. By the end of March, the $12 version was sold out, and the rest were purchased in the next two months. Paris bookshops, all of which balked at Beach’s prices, were desperate to get copies, but they were too late, and the scarcity of Joyce’s novel solidified its legendary status. Perhaps you didn’t own “Ulysses,” but you knew someone who did, and maybe you read portions of it, or maybe you only saw it high atop someone’s bookcase like some cerulean bird alighting from a canopy — and even that, over drinks with a friend, would be something to talk about. Joyce had become Paris’s newest literary celebrity. He avoided dining at his regular restaurants because people would gawk.

The backlash wasn’t far behind. A headline splashed across the entire front page of London’s Sporting Times: “THE SCANDAL OF ULYSSES.” Even D. H. Lawrence, who would later write his own unprintably obscene novel, “Lady Chatterley’s Lover,” said that the final chapter was “the dirtiest, most indecent, obscene thing ever written.” Reporters wanted to know just what Miss Beach’s father thought about it (she never asked). One paper labeled “Ulysses” “a freak production.” Another called Joyce’s rendition of Molly Bloom’s consciousness a feat of “diabolic clairvoyance, black magic.” Yet another declared “Ulysses” “the maddest, muddiest, most loathsome book issued in our own or any other time — inartistic, incoherent, unquotably nasty — a book that one would have thought could only emanate from a criminal lunatic asylum.” The asylum image became a staple of Joyce reviews.

For the people most disturbed by “Ulysses,” the scandal had nothing to do with an isolated madman. In May, James Douglas, the well-known editor of The Sunday Express in London, wrote as scathing a diatribe as he could muster.

I say deliberately that it is the most infamously obscene book in ancient or modern literature … All the secret sewers of vice are canalized in its flood of unimaginable thoughts, images and pornographic words. And its unclean lunacies are larded with appalling and revolting blasphemies directed against the Christian religion and against the name of Christ — blasphemies hitherto associated with the most degraded orgies of Satanism and the Black Mass.

Douglas claimed to have evidence that “Ulysses” “is already the Bible of beings who are exiles and outcasts in this and every other civilized country,” and it was galvanizing them all.

The sum of “Ulysses’s” objectionable parts amounted to a transgression that the word obscene did not nearly cover, and it was difficult to find a word that did. Two critics resorted to calling Joyce’s novel “literary Bolshevism,” but several readers, perhaps intuitively, thought of it as anarchism. The editor of London’s Daily Express referred to Joyce as “the man with the bomb who would blow what remains of Europe into the sky … His intention, so far as he has any social intention, is completely anarchic.” Edmund Gosse, who helped Joyce financially through the war, considered the Irish writer an extremist after “Ulysses.” It was, he said, “an anarchical production, infamous in taste, in style, in everything.”

The reaction in Ireland was no better. The Dublin Review lambasted the novel’s “devilish drench” and urged the government to destroy the book and asked the Vatican to place it on the Index Expurgatorius — merely reading “Ulysses” amounted to sinning against the Holy Ghost, the only sin beyond the reach of God’s mercy. A former Irish diplomat claimed in The Quarterly Review that Ulysses would compel Irish writers to resent the English language. Some of those writers, he predicted, would plot the literary equivalent of the Clerkenwell prison bombing (the Victorian era’s iconic Fenian assault) and blow a hole through “the well-guarded, well-built, classical prison of English literature.” But those literary terrorists could consider themselves too late, for with the publication of “Ulysses,” he announced, “the bomb has exploded.”

Nearly a century later, the reactions to “Ulysses” can feel overblown — like hype from like-minded friends and bombast from journalists trying to sell papers. These days, “Ulysses” may seem more eccentric than epoch changing, and it can be difficult to see how Joyce’s novel (how any novel, perhaps) could have been revolutionary. This is because all revolutions look tame from the other side. They change our perspectives so thoroughly that their innovations become platitudes. We forget what the old world was like, forget even that things could have been another way. And yet they were. To understand how thoroughly Joyce broke conventions, it helps to remember how stringent they were. Molly Bloom lies awake at night and thinks about getting “fucked yes and well fucked too up to my neck nearly” by Blazes Boylan. Ten years earlier, Joyce couldn’t publish “Dubliners” in part because he used the word bloody.

A beautiful narrative arc reassures us that the baffling events around us are meaningful — and this is why “Ulysses” appeared to be an instrument of chaos, an anarchist bomb.

More like this

What made “Ulysses” revolutionary was that it was more than a bid for marginally wider freedom. It demanded complete freedom. It swept away all silences. An angry soldier’s threats in Nighttown (“I’ll wring the bastard fucker’s bleeding blasted fucking windpipe”), Molly’s imaginary demands (“lick my shit”) and Bloom’s appalling image of the Dead Sea (“the grey sunken cunt of the world”) are declarations that henceforth there would be no more unspeakable thoughts, no restrictions on the expression of ideas. This is why printing the word fuck was more than schoolboy mischief. “He says everything — everything,” Arnold Bennett marveled. “The code is smashed to bits.” “Ulysses” made everything possible.

Dirty words were only part of the code-smashing liberation (“Mrs. Dalloway,” after all, didn’t need to be dirty to need “Ulysses”). The code that “Ulysses” smashed was conceptual. For beyond liberation from silence, “Ulysses” offered liberation from what we might call the tyranny of style: from the manners, conventions and forms that govern texts almost without our realizing it. The novel as an art form had long been about breaking the tyranny of style, but “Ulysses” removed narrative elements no one considered removable. A single narrator guiding the reader through the story was gone. The contextual armature that helps a reader make sense of events was gone. Clear distinctions between thoughts and the exterior world were gone. Quotation marks were gone. Sentences were gone. In the place of style we are left with borrowed voices and provisional modes, all of which are fleeting, all of which, as T.S. Eliot told Virginia Woolf, reduce style to “futility.”

But why should it matter? The end of style seems a long way from Fenian bombs and the collapse of civilization, yet the critics’ comparisons were trying to capture the novel’s apparent recklessness. To turn style into futility, it seemed, was to lay waste to all foundations. When a well-known poet named Alfred Noyes delivered a lecture in front of the Royal Society of Literature in October 1922, he launched into a familiar diatribe about the unprecedented obscenity of “Ulysses.” But what infuriated Noyes most was that Joyce’s emergence signaled the degradation of the United Kingdom’s foundational values. Literary critics were casting aside the best of English literary tradition for madmen calling themselves modernists. It was as if an entire civilization were in the process of forgetting itself.

To be oblivious of English values did not strike Noyes as a matter of losing the past. It struck him as a matter of losing grasp of reality. “The lack of any conviction that there are realities, standards, and enduring foundations in literature has had a deadly effect,” he told the Royal Society. Groundless literary criticism was introducing “elements of chaos” into the minds of the younger generation.

He had a point. Narratives are the way we make sense of the world. We parcel existence into events and string them into cause-and-effect sequences. The chemist comparing controls and variables and the child scalded by a hot stove are both understanding the world through narrative. Novels are important because they turn that basic conceptual framework into an art form. A beautiful narrative arc reassures us that the baffling events around us are meaningful — and this is why “Ulysses” appeared to be an instrument of chaos, an anarchist bomb. To disrupt the narrative method was to disrupt the order of things. Joyce, it seemed, wasn’t devoted to reality. He appeared to be sweeping it away.

If you were a modernist — if you believed the order of things was already gone — you thought differently. Eliot defended “Ulysses” by objecting to its critics’ premise. Life in the age of world war was no longer amenable to the narrative method, and yet “Ulysses” showed us that narratives weren’t the only way to create order. Existence could be layered. Instead of a sequence, the world was an epiphany. Instead of a tradition, civilization was a day. The chaos of modernity demanded a new conceptual method to make sense of the contemporary world, to make life possible for art. And that is what “Ulysses” gave us.

Copyright © 2014 by Kevin Birmingham