Mastering move with high level of difficulty, prize-winning execution

Concussion forced Marissa Sumathipala to give up her Olympic figure-skating dreams but put her on neuroscience path

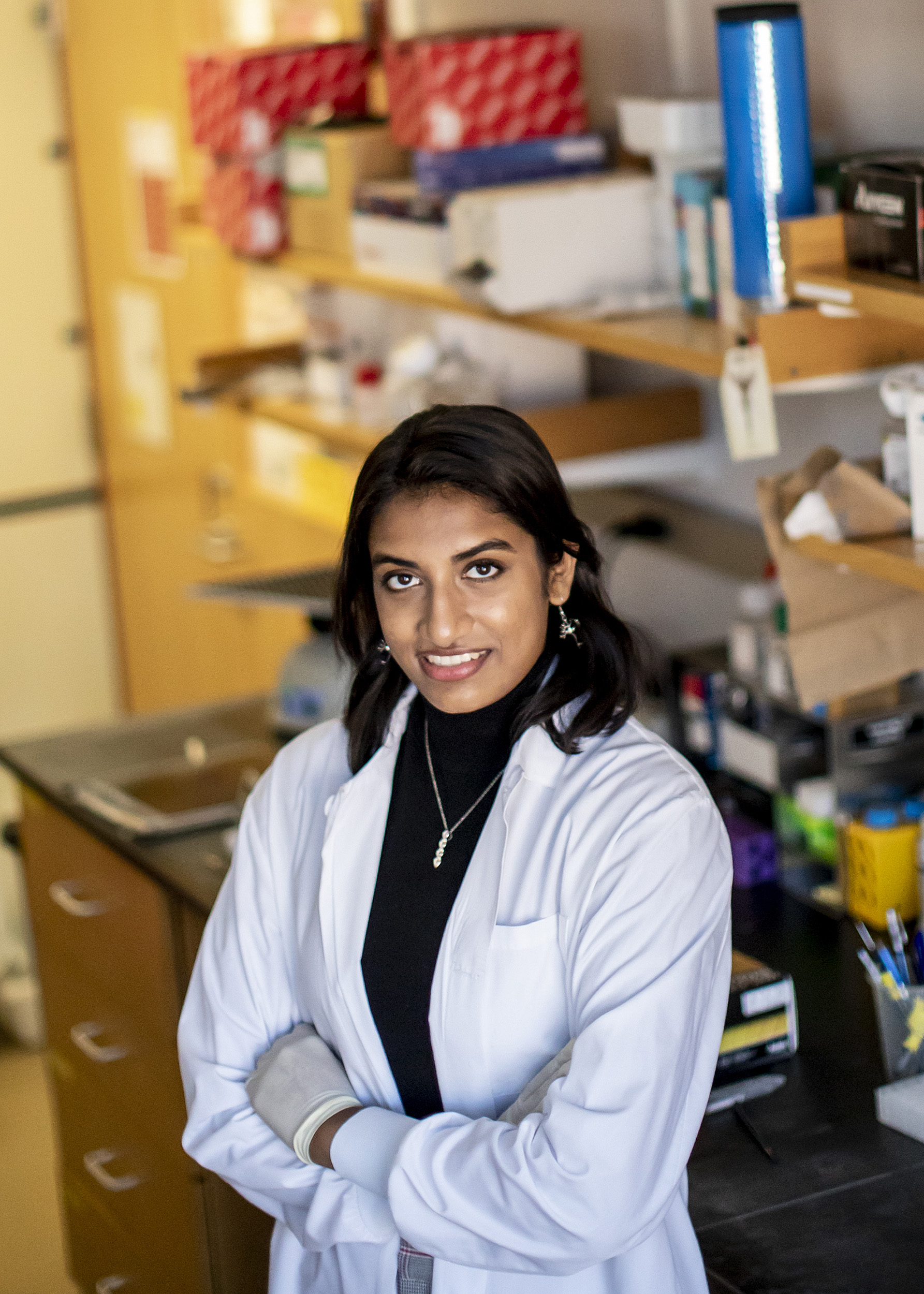

Marissa Sumathipala was an Olympic hopeful, started a company at 17, and is now graduating Harvard.

Rose Lincoln/Harvard Staff Photographer

This story is part of a series of graduate profiles ahead of Commencement ceremonies in May.

Marissa Sumathipala was practicing with her recreational figure-skating team when it happened. The sophomore at Broad Run High School outside of Washington, D.C., had just finished a serious training session for a major competition that could put her on a path for nationals. This one was for fun.

In the midst of choreographing a routine, she collided with another skater. “My head slammed against the ice,” Sumathipala said. Everything went black.

Up to that point, Sumathipala’s entire life had revolved around her sport — her daily schedule, exercise routine, even her diet. She was homeschooled during middle school so she could train full-time. Sumathipala had hopes of making the 2018 Olympic team. The fall on the ice would change everything, including her direction.

“I had a concussion and it put me out of commission, ending my skating career,” she said.

Symptoms lingered for years. Her memory felt hazy at times. She’d randomly find herself dizzy, nauseated, or fatigued. Sumathipala consulted doctors, so many that she “lost count.”

But no one had answers.

“I began to realize that there was so much that we didn’t know about the brain,” Sumathipala said. “And that gap in what we understood about the brain had such devastating impacts for patients like myself, but also all the people that I saw in the waiting rooms and support groups that I went to during this experience.”

She set out to find the answers herself, a path that would eventually bring her to Harvard, where she’d concentrate in neuroscience and study synapses in the human brain.

The daughter of immigrants, 15-year-old Sumathipala plunged into science. She’d already done some independent research at Johns Hopkins School of Medicine at 14 under a scientist there after attending a talk and connecting with them.

At age 16, she landed a research position in her hometown of Ashburn, Virginia, at the Howard Hughes Medical Institute Janelia Research Campus, where she studied how fruit flies make behavioral decisions.

A year later, she created Theraplexus, a computational platform that uses network science analytics and artificial intelligence to map molecular interactions and provide better drugs for chronic diseases like cancer, Alzheimer’s, diabetes, and heart disease.

At Harvard, she continued building up experience as a researcher by working stints at several labs with different focuses. Most of all, she homed in on brain science.

Throughout her four years, she worked with the McCarroll Lab at Harvard Medical School, helping develop a new method for sequencing synapses in the brain, which are crucial for memory and learning and result in maladies like Huntington’s disease when they go wrong.

She developed a method to separate synapses from rest of the cell and encapsulate each into tiny nanoliter droplets to capture the RNA molecules and sequence them. This could one day help shed light on the role of synapses in brain development, disease, and human cognition. Her work builds on technologies developed in the McCarroll Lab for sequencing RNA in single cells. Her work there became her thesis project.

Even as an undergraduate, Sumathipala quickly became a trusted and valued member of the lab, said Steven A. McCarroll, the Dorothy and Milton Flier Professor of Biomedical Science and Genetics. He remembers the lasting first impression she made on him that convinced him to bring her on the team.

“She first came to talk to me about doing research the summer before she even started [at Harvard],” McCarroll said. “I was struck by how mature her thinking already was about science. … She had read a lot of papers, and she just had a very mature sense of what kind of research she wanted to pursue and was willing to travel across the river to do it … that’s very unusual for undergraduate.”

Sumathipala has won two major awards that will propel her into the future: the Churchill and Gates Cambridge scholarships, which both support graduate study abroad at the University of Cambridge.

In the fall, with the Churchill, Sumathipala plans to apply some of the techniques she developed at the McCarroll Lab to artificially grown tissues called organoids to study what causes dementia and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. She will use the Gates scholarship to pursue a Ph.D. in clinical neuroscience.

Outside of Harvard, Sumathipala has volunteered at an international nonprofit called iGEM, where she’s been hosting workshops to teach scientists how to talk to the public and build trust. She was spurred to action by all the misinformation going around during the pandemic.

Reflecting on her years at Harvard, Sumathipala said one of the things she’s most grateful for is seeing how things have come full circle for her.

Sumathipala competed with the Harvard Figure Skating Club all four years. She helped increase its membership and introduced new skaters to the sport she still loves.

“I spent a long time grappling with my identity,” she said. “Growing up I was just a skater and then, when I got concussed, I had to rebuild my identity. Then I was a scientist. Now, I identify as being both a skater and a scientist.”