Elijah Suh ’22 (top right) and his family celebrate his mother’s 53rd birthday in Misawa, Japan, last year. Clockwise from top left are siblings Jeremiah, Hannah and Joshua, and parents David and Karen.

Photo courtesy of Elijah Suh

Getting through it together

Before COVID, a cancer diagnosis. Here’s how one family grew closer even as the world seemed to come apart.

This article is the first entry in a three-part series about family life during the pandemic. Read the second and third.

It was March of 2020 and Elijah Suh ’22 was at a San Diego hospital listening to a doctor discuss survival rates that had nothing to do with COVID-19. After the pandemic forced Harvard to close campus, Elijah had flown to California to be with his mother as she underwent and recovered from a double mastectomy.

A chemistry concentrator on a pre-med track, Elijah had studied cancer in the classroom. But reviewing the prognosis of the disease in the pages of a textbook was one thing; hearing an expert 5 feet away talk about the life of someone he loved was something else entirely.

“When it’s about your own mom and you hear a doctor speaking in empirical terms about survival rates and lasting damage — it’s chilling,” Elijah said. Even with a 95 percent chance of a full recovery, he couldn’t help but think about the other 5 percent.

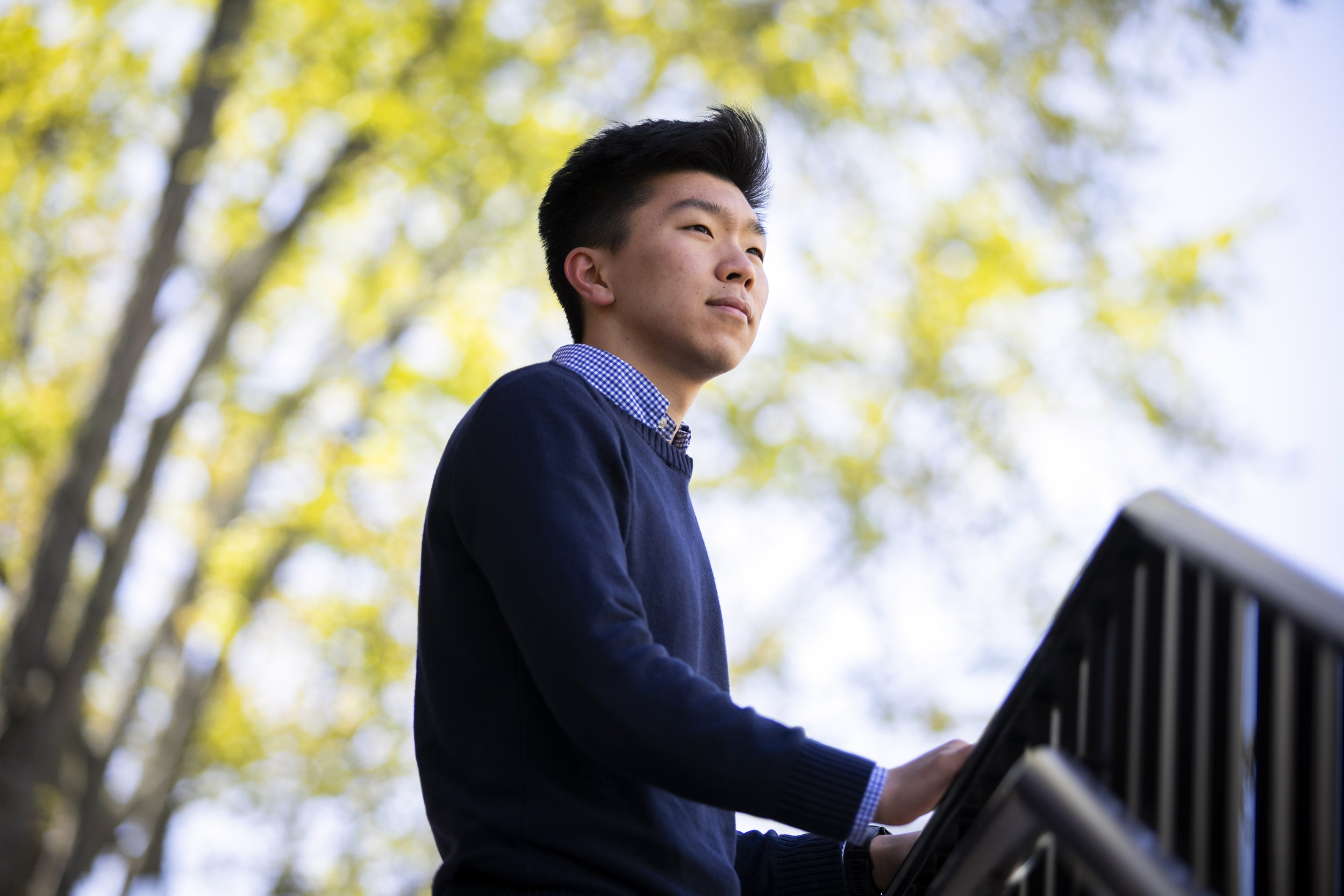

After spending part of the pandemic in California and Japan, Elijah returned to campus thankful for both the mundane — being in the same time zone with his professors and classmates — and the more meaningful — deeper connections with family and friends.

Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

Packing his stuff and relocating to a new state, or even a new country, was nothing new for the Kirkland House resident, who had grown up following his father’s Air Force career around the globe. But leaving campus in the face of a lethal virus to join his mother for a major operation was unnervingly different. Yet while Elijah may have been worried, he tried not to let it show. His goal was to support his mom through the surgery — to “just be there with her in case anything happened.”

Still, when the time came, the role reversal wasn’t easy.

“To see my mom, who’s always been this very independent, very strong person in my life, in a physically vulnerable state and so uncomfortable was hard,” said Elijah. “I joke that I kind of helped nurse her back to health. I think she would have been fine without me, honestly … but just being present I think was very helpful, for my sake, and especially for hers.”

“I think it’s hard for a parent to be more vulnerable to their children.”

Elijah Suh

A few months before, Karen Suh, a vigorous 54-year-old, was living with her family on a military base in Misawa, in northern Honshu, Japan’s largest island, and teaching at its elementary school when she received the results of a routine mammogram. Her doctors recommended she fly to a San Diego breast center for treatment. “My radiologist told me frankly, ‘I think it’s cancer,’” Karen said.

In February, tests in California confirmed her fears and soon Karen was managing worries about her diagnosis with her concern about the pandemic as death rates rose and hospitals began accepting only the sickest patients. “We had to do the biopsy, wait for the results, then try to schedule the operation, and during that span, everything exploded,” she said. “I was told that my surgeon really had to fight for me to get the surgery done.”

She’d arrived from Japan with her husband, who stayed with her for the surgery while her daughter, Hannah, looked after her two youngest sons in Misawa. Elijah remained in San Diego when his father, David, was called back to the base 5,000 miles away. He helped his mother with her recovery — driving her to follow-up appointments and attending to her meals and medications — and finished up his classes online. Within days they began hearing about cases of severely ill patients filling intensive care units in California and across the country. Rising fears about the spread of the virus prevented them from seeing family members who lived nearby. Increasingly isolated, they kept the TV trained on the news, hungry for information about the origins of the virus and how to avoid infection. “Answers … that’s the only thing we wanted,” said Elijah.

Elijah says time spent with his mother in the early days of the pandemic in San Diego gave them a chance to bond.

Photo courtesy of Elijah Suh

“Even though there was chaos breaking out everywhere it was just kind of like very peaceful.”

Karen Suh

But when mother and son reflect on the early days of the pandemic, they look past the dread. Both took remote classes as Karen recovered; she learned how to help dyslexic children read and he finished up his coursework. They passed their days as students, and when school was over, simply enjoyed each other’s company. Karen remembers those few months as “very special.”

“Even though there was chaos breaking out,” she said, “it was kind of peaceful with just the two of us.”

Elijah agreed. The time he and his mother spent together in a hotel on a base in San Diego, he said, gave them a chance to bond. They took long walks along the shore and shared dinners and deep conversations. “We made the most of it in terms of trying to understand one another better,” said Elijah. “I think it’s hard for a parent to be more vulnerable to their children.”

Soon they focused their efforts on getting back to their family. “We were worried about my mom’s compromised immune system,” said Elijah, “and I think we converted that worry in efforts to get back to Japan as soon as we could.”

* * *

Hannah Suh was taking care of her two younger brothers and trying to reconcile concerns about the deadly virus in the United States with the relative calm that surrounded her in Misawa, which had so far remained largely free of infection. On a gap year before heading to UCLA, she had been looking forward to spending more time with her parents. Then, overnight, she became head of the household, as COVID fears gradually took hold.

“I was the only one who left our house at the time, because I was the only one who could drive … I would go out if we whenever we would need groceries or anything like that,” she said.

Hannah missed her parents and worried about her mother’s health, but looking after her two “rambunctious” brothers, ages 12 and 15, helped keep her mind occupied. “I think it definitely taught me a lot about responsibility.”

Elijah remembers how impressed he was with his sister’s poise.

“She was essentially encountering the pandemic all by herself, and she was responsible for my younger brothers. But she stepped up to the test marvelously.”

Sunset walks in Misawa and San Diego.

Photos courtesy of Elijah Suh

“I think I still tend to be more pessimistic, but the pandemic has really showed that it just isn’t a way to live.”

Elijah Suh

In May, her parents and Elijah made it back to Japan, and soon it became clear that Hannah, like so many other students, would spend her first year of college as a remote learner. With California 16 hours behind Misawa, she “had to go nocturnal,” staying awake into the early hours to attend her classes whenever she could. It helped that her big brother was on a similar schedule. “We had our shared struggles,” said Hannah, “so I think we were able to bond more. I am definitely grateful for that.”

Elijah found himself living in two different worlds. On the base, his family adhered to precautions enforced by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. In the community, rules and regulations differed. Mandates and lockdowns ebbed and flowed depending on case counts and the fears of local officials. Sometimes the Suhs were free to go out, even visit restaurants unmasked; at other times they were confined to their home — two side-by-side three-bedroom units with an adjoining door.

Snow starts to melt on the air base in Misawa.

Photo courtesy of Elijah Suh

As the eldest sibling, Elijah enjoyed the opportunity to help his brothers with a trigonometry question or a tricky verbal passage on a PSAT prep test. Guiding his sister through general chemistry or her first college-level writing course also felt good. “Instead of calling me from across the country, she could just walk into my room,” he said. “It was so nice to be able to offer her advice and to watch all of my siblings grow academically. I felt blessed to see that.”

But it wasn’t always smooth sailing. Too much togetherness could sometimes lead to frayed nerves, and then there was the monotony of one cramped day after another. Long walks and Walt Disney were welcome coping mechanisms, Elijah said. “We had never subscribed to a streaming platform before, but I felt like out of desperation, because I think we were so bored, my dad finally bought us Disney Plus. And I don’t think I can overstate how big a deal that was for our family.”

* * *

Karen, who is healthy today, looks back with a deep sense of gratitude for the time she got to spend with her family while so many others experienced profound sorrow and loss. “It was our own little corner of the world,” she said.

Elijah returned to Cambridge thankful for both the mundane — being in the same time zone with his professors and classmates — and the more meaningful — deeper connections with family and friends.

“My family supported me when I had to wake up in the middle of the night for class, or when I was falling asleep at 2 p.m.,” he said. “And I am so glad my mom was able to rely on myself and my dad. I’m glad she didn’t try to soldier through her pain and discomfort, and everything that comes with being a patient. Instead, she let us help her.

“I think I still tend to be more pessimistic, but the pandemic has really showed that it just isn’t a way to live,” he added. “If you look forward, you will find people who care. And that makes me want to care about other people.” Accordingly, his next academic stop will be the University of Cambridge in England, where he’ll study for a master’s in chemistry as part of his plan to eventually enroll in medical school.

The pandemic, said Elijah, “gave us all opportunities to individually grow. And you really can’t trade that.”