A new study by economist Claudia Goldin finds that despite “stresses, anxieties, and frustrations” of the pandemic, women with college degrees largely kept working.

BBVA Foundation

Women mostly stayed in workforce as pandemic unfolded, defying forecasts

Harvard economist says education a larger factor than gender in labor changes

Predictions about a COVID-era exodus of women from the workforce have not come to pass, according to research from Harvard economist Claudia Goldin.

In a recent working paper, the Henry Lee Professor of Economics reports that women largely stayed in the labor force in the first year and a half of the pandemic despite health concerns, heightened demands on their time, and increased care commitments.

“There was tremendous strain and stress during the early months of the pandemic and into the first year, but in fact, women by and large persisted,” said Goldin. “It wasn’t that the strains and anxieties of the pandemic were great because women dropped out. They were great because women stayed” in the labor force.

Her paper, published by the National Bureau of Economics Research, challenges reports such as a 2020 “Women in the Workplace” finding by McKinsey & Co. and LeanIn.org that one in four women were considering leaving their jobs.

That figure was an expression of the “stresses, anxieties, and frustrations” of the pandemic, said Goldin. “This was the first moment in a very long time in American history when we had a collective sense that the economy really is running more on women than ever before.”

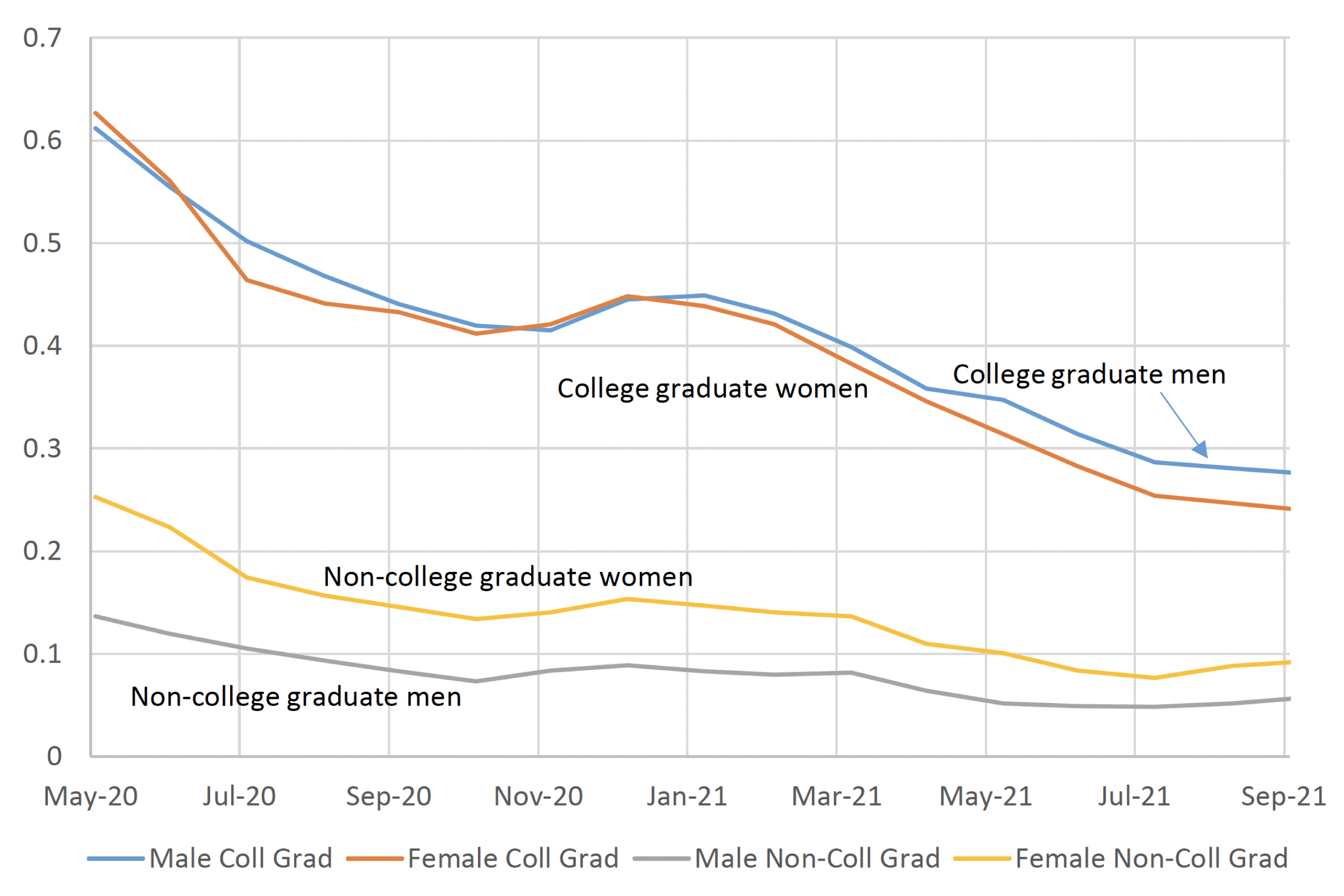

Goldin’s analysis, which uses data from the American Time Use Survey, the Current Population Survey, and other sources, reveals that education, not gender, was the main distinction between people who stayed in their jobs and those who did not amid the economic shockwaves of the pandemic.

For women in particular, the difference was striking. Those without a college degree left their jobs at almost twice the rate of those who had one. Women with college degrees were more likely to have jobs that allowed them to work from home, Goldin says. Even though they spent much more time supervising children and caring for elderly relatives than in pre-pandemic times, their jobs shielded them from some economic volatility and health risks, according to her research.

Fraction of employed men and women aged 25-54 who worked remotely due to COVID-19, May 2020-September 2021, by education.

“Understanding the Economic Impact of COVID-19 on Women,” Claudia Goldin

The economic impact of the pandemic fell heavily on Black and Hispanic women, mothers of young children, caregivers for parents, and women who did not have the option of remote work.

“Those women were disproportionately in sectors that were shut down by states at the beginning of the pandemic and then had reduced density and demand for much of 2020,” including salons, restaurants, retail, daycare centers, and hotels, said Goldin.

She noted that Black women were likelier to work in service occupations before the pandemic and, therefore, were likelier to be furloughed or laid off in its early months. They were also more likely to face illness or care responsibilities at home, making a return to work more difficult.

Interestingly, the number of women with a college degree and children under age 4 who were “at work” was almost 4 percentage points higher in spring 2021 compared with spring 2018, while mothers of young children without a college degree saw a drop of 4.4 percentage points in their “at work” status over the same period. Goldin speculated that new mothers who could work from home and otherwise may have left the labor force “decided to remain in.”

Goldin stressed that pandemic-era pressures on women and families are real and should not be ignored. The issues captured by the McKinsey/LeanIn.org survey and other measures indicates a need for bigger changes to help parents, including more robust childcare infrastructure.

“In the U.S., we have a crazy quilt of afterschool and child-care programs,” she said. Governments and businesses “could do something that makes more sense, because child care is exactly what we need now to have the most efficient workplaces.”

As for the office, Goldin said the pandemic may have offered some silver linings for women as managers adopted more flexible policies. “We have learned a tremendous amount about how to reduce the cost of flexibility,” she said.

But she also warned of pitfalls that could arise as part of a “new normal” for women: “We want to make certain that we don’t create female enclaves of remote work that inhibit advancement, as part-time work has often done. To enhance gender equity, it would be good if men are encouraged to do a hybrid schedule as well.”