An exhibit with legs

Restored papier-mâché octopus is grabbing attention in its new home

The life-size model of the giant Pacific octopus in its new home at the Northwest Labs building.

Photos by Kris Snibbe/Harvard Staff Photographer

It’s been waving to the Harvard community for 140 years.

With each arm measuring more than 8 feet, this life-size model of a giant Pacific octopus arrived on campus circa 1883 shortly after it was constructed. Fans of the invertebrate know it’s male due to the presence of a hectocotylus, or a single arm that doubles as the reproduction organ.

Scientific illustrator James H. Emerton created the lifelike specimen at Yale University under the guidance of zoologist Addison E. Verrill, Harvard Class of 1862. Earlier this month, the Enteroctopus dofleini was removed from its longtime digs at the Harvard Museum of Natural History, where it lived under less-than-ideal viewing conditions, hanging from a classroom ceiling.

Sylvie Laborde, acting director of exhibitions and a senior designer for Harvard Museums of Science and Culture, said few people encountered the octopus, and only saw its underside. The centenarian cephalopod also needed TLC. Emerton had crafted it from papier-mâché, rubber, and other 19th-century materials. “Pieces were breaking off and falling on the floor,” said Laborde, who served as project manager for the model’s restoration and relocation at the Northwest Labs building.

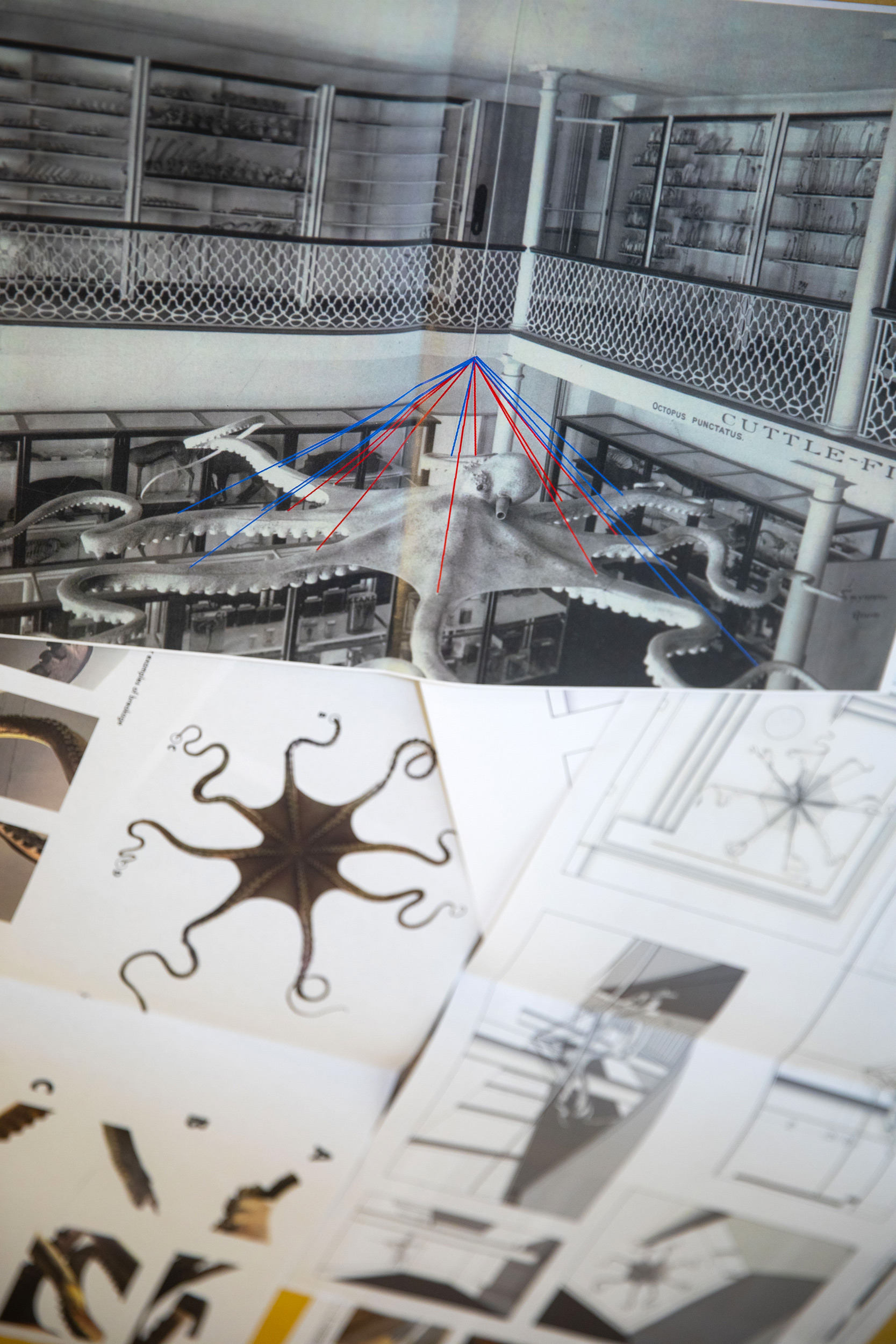

Planning details for the restoration and hanging of the octopus along with careful touch-ups by Terry Chase.

Emerton based the octopus on several smaller specimens. Only after consulting with a Smithsonian biologist — who relayed the tale of a much larger specimen — did Emerton feel comfortable upping the proportions. The model measures about 14 feet across; it would be 22 with arms fully extended. “You can come up close and appreciate that this is the size it could be in real life,” said Breda Zimkus, director of collections operations for Harvard’s Museum of Comparative Zoology, which owns the model. She noted that this particular species is found in coastal waters of the North Pacific from Asia to North America.

Moving the octopus took more than seven people from multiple Harvard departments. Terry Chase, a global leader in building and designing natural history exhibits, was engaged to lead the project’s repair and conservation phase. “To preserve the model’s historical integrity,” Laborde explained, Chase used “the old technique” of papier-mâché in mending the piece.

Wires used to display the octopus from the ceiling. Tristan Rocher (from left), exhibit production and maintenance manager (HMSC), Jon Woodward, senior curatorial technician (MCZ), Amanda Kressler, exhibit production specialist (HMSC), Breda Zimkus, director of collections operations (MCZ), and Zachary Stern, exhibit designer (HMSC) hang the model.

And when it came time to hoist the creature to its new home — suspended over an airy Northwest Labs stairwell, next to a northern bottlenose whale skeleton — the team ensured prime viewing from multiple angles. The octopus’ eyes are visible from one level, the spiral of undulating arms from another. Tip: Make the trip downstairs for the fullest view of its pinwheel form.

Laborde has another tip: Try visiting the octopus at night, especially once special lighting is installed later this year. “Even when you walk outside, there’s an amazing view of the octopus,” she said. “We gave it a bigger public and a second life.”

Tristan Rocher (left) and Amanda Kressler under the octopus in its new home.