So who is included in King’s ‘beloved community’?

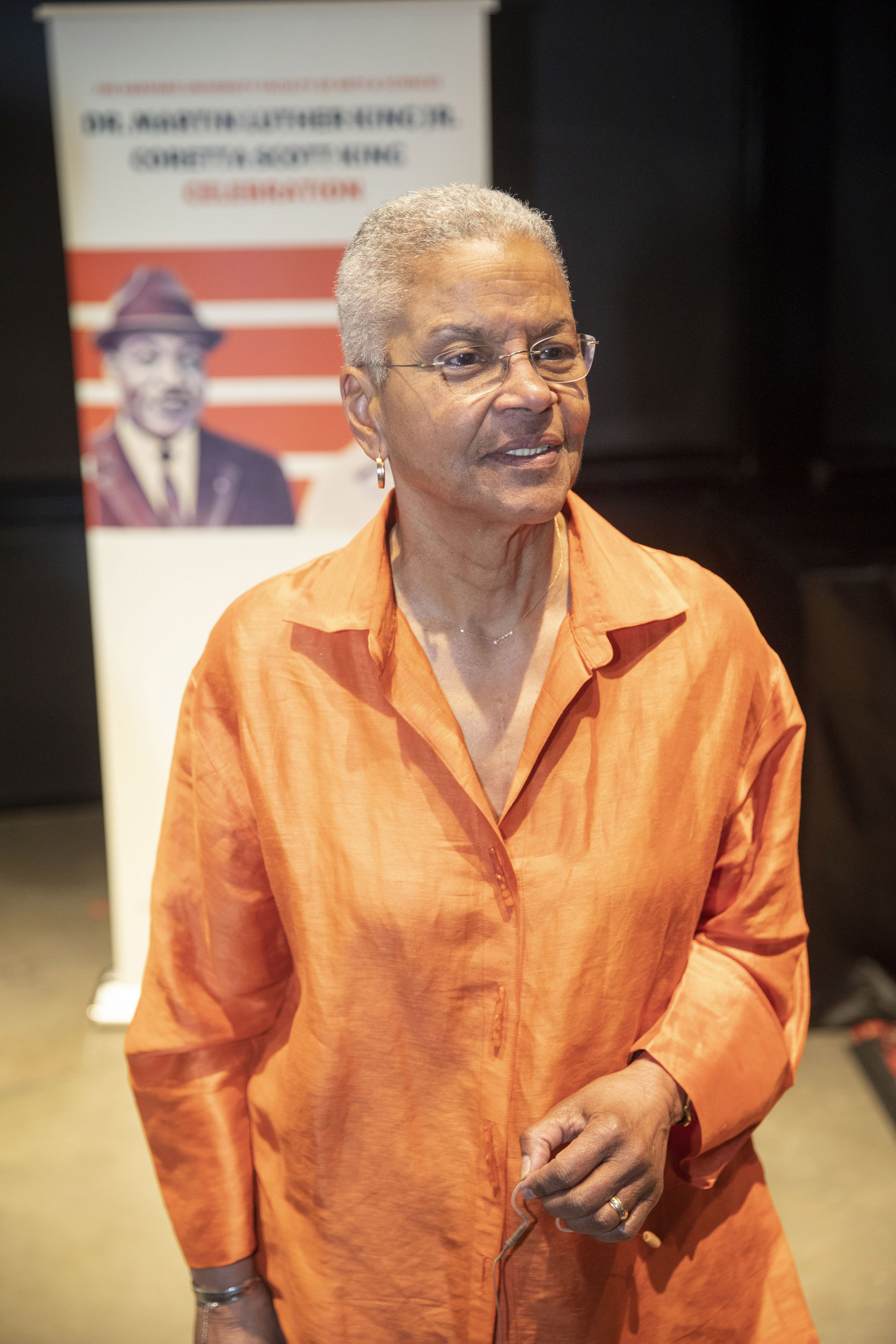

Black queer poet, scholar Cheryl Clarke discussed place of LGBTQ community in American culture at FAS event

“The practice of ‘beloved community’ is a life practice,” Clarke said in a recent Harvard lecture. “Any community that calls itself beloved has to have a deep commitment to feminism and women’s leadership.”

Kris Snibbe/Harvard Staff Photographer

In a recent lecture capping off a two-day residency honoring the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and Coretta Scott King, Black queer poet and scholar Cheryl Clarke explored the concept of “beloved community” and whom the Kings meant to include in their vision of an inclusive, nonviolent society governed by human decency.

“Figures such as James Baldwin, Bayard Rustin, Audre Lorde, along with Coretta Scott King and John Lewis, have helped pave the way for the inclusion of LGBT people as beloved members of communities across the nation and the world,” Clarke said. “Yet we are still asking the questions, ‘Whose “beloved community”?’ ‘Who is among the beloved?’”

The social justice activist outlined how LGBTQ people must include themselves within that community in a talk last week hosted by the Faculty of Arts and Sciences’ Office for Equity, Diversity, Inclusion, and Belonging.

“What was King talking about [in his ‘beloved community’ speech]? A hope for the future. An interracial community dedicated to peaceful and steadfast insistence on faith, in radical coexistence and radical revisioning of living in the world. The practice of ‘beloved community’ is a life practice,” Clarke said, adding, “Any community that calls itself beloved has to have a deep commitment to feminism and women’s leadership.”

Clarke recounted a story from 1983 in which King’s widow stood in defiant support of Black lesbian poet and Civil Rights activist Audre Lorde, who was set to speak at the 20th anniversary rally of King’s March on Washington. Walter Fauntroy, then delegate to the U.S. House representing Washington, D.C., complained that including Lorde would be seen as the March “endorsing homosexuality.” Scott King responded that Lorde “is esteemed. She must speak.”

Scott King maintained her support for LGBTQ rights until her death in 2006.

Cheryl Clarke reads her poem ‘48 Years’

transcript

Transcript:

CLARK: Martin Luther King Jr. Mike and silk suits and pajamas. Did he benefit the negro? Did he hate women? Or just Ella Baker? Did he do more for the negro than Jackie Robinson? King would come in Birmingham or Albany or Selma or Memphis in two ways. Way one. According to witness, during the day, and with him come the paparazzi and the front page Pulitzer winners. And then in three days, King leave and leave the cleanup to the foot soldiers. Way two. According to legend, by night with his crowd of preachers and such after a plate of short ribs, mac and cheese, collard, candied sweets, and despite endless self-recrimination after, King would say to his confrères, ‘time to go souling.’ Lived a charmed life King did. Long as he lived it.

Like Lorde and other Black lesbian activists before her, Clarke has been proud and vocal about her identity.

“What I’ve always admired and loved about her is her fierce and brave commitment to living as a lesbian on our own terms,” said Clarke’s long-time friend Evelyn Hammonds, Barbara Gutmann Rosenkrantz Professor of the History of Science, professor of African and African American Studies and professor in the Department of Social and Behavioral Sciences, T.H. Chan School of Public Health, in a prerecorded message. “I am so grateful that she taught me how to be a brave and free Black lesbian feminist committed to remaking the world in our own images and in our own language.”

Clarke said in an interview with the Gazette that she continues to be influenced by the work of Lorde and Pulitzer Prize-winning poet Gwendolyn Brooks. During her career, Clarke has written on a wide range of topics, including JFK’s assassination, the Black Arts Movement, and her own life as Black lesbian. Instead of letting the news or topic du jour dictate her poetry, Clarke said she decides what to write about based on what she thinks people need to be educated on or what needs to be said at a given time.

Clarke pointed to her 2016 book, “By My Precise Haircut,” as her favorite work because it showcased the evolution of her poetry. She previously wrote in a narrative style before transitioning to more lyrical work. Clarke responds in the book to cultural and political currents while writing about her concerns, including Black women, sexuality, jazz, rhythm and blues, lesbianism, and slavery. She dedicated her book to Sandra Bland, whose 2015 death in a jail cell after a traffic stop was ruled a suicide, and “all Black women who have died unarmed at the hands of the state.”

As part of her residency, Clarke spoke with students taking a class called “Freedom Writers” by Jesse McCarthy, assistant professor of English and of African and African American Studies, and at a poetry reading at the Barker Center of her work from 1982 to the present.

“The opportunity to commune with someone so central, so undeniably influential to the Black queer literary tradition was an honor,” said Imani Davis, a Ph.D. candidate whose work focuses on African American poetry and poetics. “I definitely feel a renewed sense of possibility as a fellow poet and critic whose identity aligns with that lush history.”

For those hoping to follow in her footsteps, Clarke had simple advice. “You just have to write. That’s my advice,” she said. “However, you do it. If you say you’re a poet, you have to be where the poets are, and you have to be doing the work.”