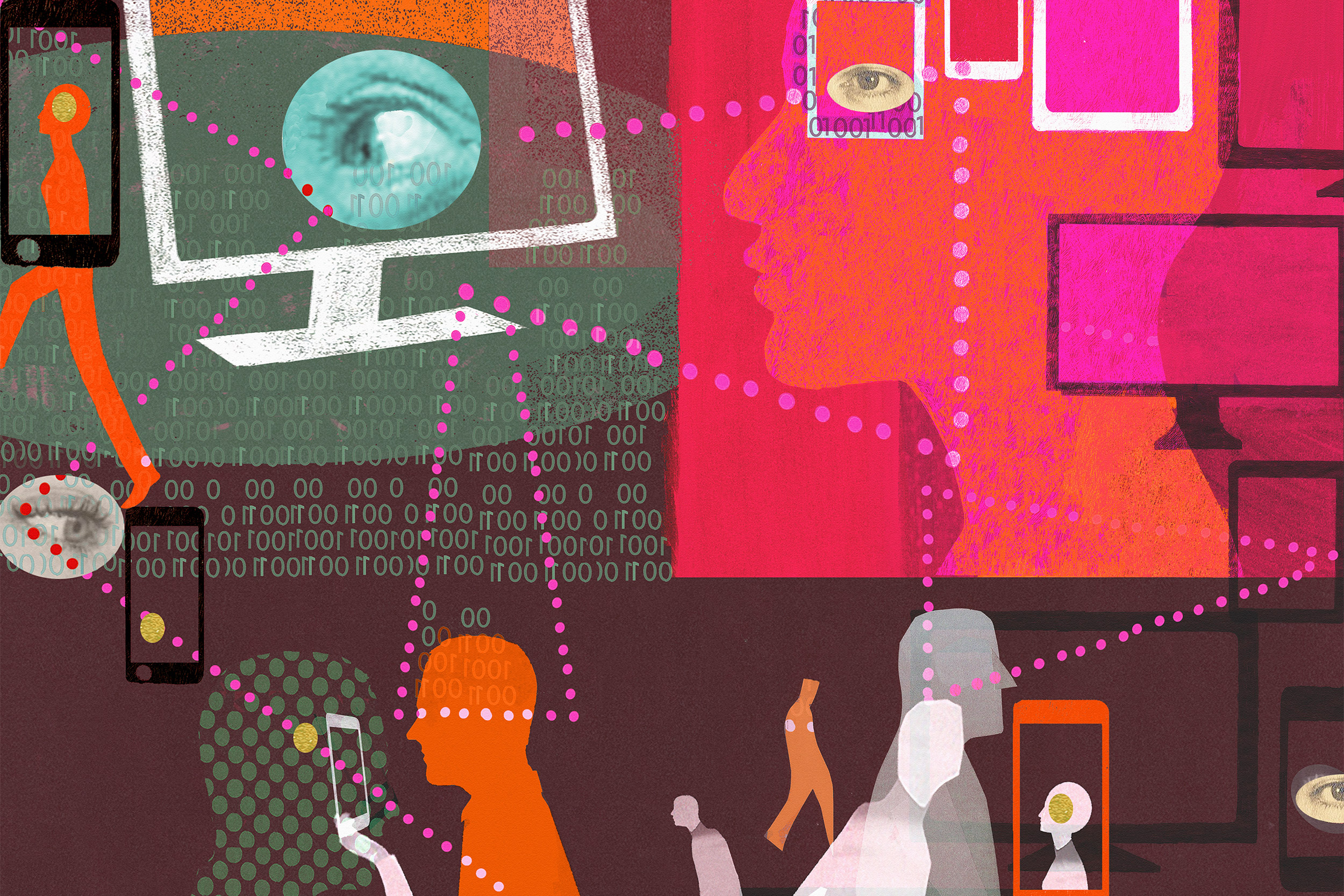

Illustration by Donna Grethen/Ikon Images

Fighting for our cognitive liberty

Dangers involved in rise of neurotechnology that allows for tracking of thoughts, feelings examined at webinar

Imagine going to work and having your employer monitor your brainwaves to see whether you’re mentally tired or fully engaged in filling out that spreadsheet on April sales.

Nita Farahany, professor of law and philosophy at Duke Law School and author of “The Battle for Your Brain: Defending the Right to Think Freely in the Age of Neurotechnology,” says it’s already happening, and we all should be worried about it.

Farahany highlighted the promise and risks of neurotechnology in a conversation with Francis X. Shen, an associate professor in the Harvard Medical School Center for Bioethics and the MGH Department of Psychiatry, and an affiliated professor at Harvard Law School. The Monday webinar was co-sponsored by the Harvard Medical School Center for Bioethics, the Petrie-Flom Center for Health Law Policy, Biotechnology, and Bioethics at Harvard Law School, and the Dana Foundation.

Farahany said the practice of tracking workers’ brains, once exclusively the stuff of science fiction, follows the natural evolution of personal technology, which has normalized the use of wearable devices that chronicle heartbeats, footsteps, and body temperatures. Sensors capable of detecting and decoding brain activity already have been embedded into everyday devices such as earbuds, headphones, watches, and wearable tattoos.

Sensors capable of detecting and decoding brain activity are already embedded into everyday devices, which is why safeguards to protect people’s freedom of thought should be implemented now, says Nita Farahany, author of “The Battle for Your Brain.”

Kris Snibbe/Harvard Staff Photographer

“Commodification of brain data has already begun,” she said. “Brain sensors are already being sold worldwide. It isn’t everybody who’s using them yet. When it becomes an everyday part of our everyday lives, that’s the moment at which you hope that the safeguards are already in place. That’s why I think now is the right moment to do so.”

Safeguards to protect people’s freedom of thought, privacy, and self-determination should be implemented now, said Farahany. Five thousand companies around the world are using SmartCap technologies to track workers’ fatigue levels, and many other companies are using other technologies to track focus, engagement and boredom in the workplace.

If protections are put in place, said Farahany, the story with neurotechnology could be different than the one Shoshana Zuboff warns of in her 2019 book, “The Age of Surveillance Capitalism: The Fight for a Human Future at the New Frontier of Power.” In it Zuboff, Charles Edward Wilson Professor Emerita at Harvard Business School, examines the threat of the widescale corporate commodification of personal data in which predictions of our consumer activities are bought, sold, and used to modify behavior.

A renowned expert on the ethics of neuroscience, Farahany advocates for the need to include cognitive liberty as a universal human right. The term was coined by neuroethicist Wrye Sententia and legal theorist and lawyer Richard Glen Boire in response to the increasing ability of technology to monitor and manipulate cognitive function.

Cognitive liberty should be recognized as both a legal and a societal norm and should be reflected in international human rights law, Farahany said. She added that the mechanism to do it is by updating the definition of privacy to include mental privacy, and updating freedom of thought to include freedom from interception, manipulation, and punishment of our thoughts, as well as self-determination.

“Cognitive liberty is the right to self-determination over our brains and mental experiences, as a right to both access and use technologies, but also a right to be free from interference with our mental privacy and freedom of thought,” said Farahany.

The impact of neurotechnology on human life could bring both benefits and ills. Corporations and governments are already hacking into people’s brains, but sensors could revolutionize health care by enabling early detection of presymptomatic cognitive decline, including Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s disease, and dementia, and support clinical interventions. It could be transformational for people’s health and equal access to it should be encouraged, Farahany said.

Farahany finds hope in people’s growing concerns about the role of artificial intelligence in work and life in general, but she warns that action must be taken now.

She said there is a “very Orwellian vision of this future that’s ahead of us if we don’t make some radical changes now. I am optimistic in this moment that those kinds of radical changes are possible, and that we have the political will and the collective consciousness to do so. But if we don’t make those choices, it won’t be good.”