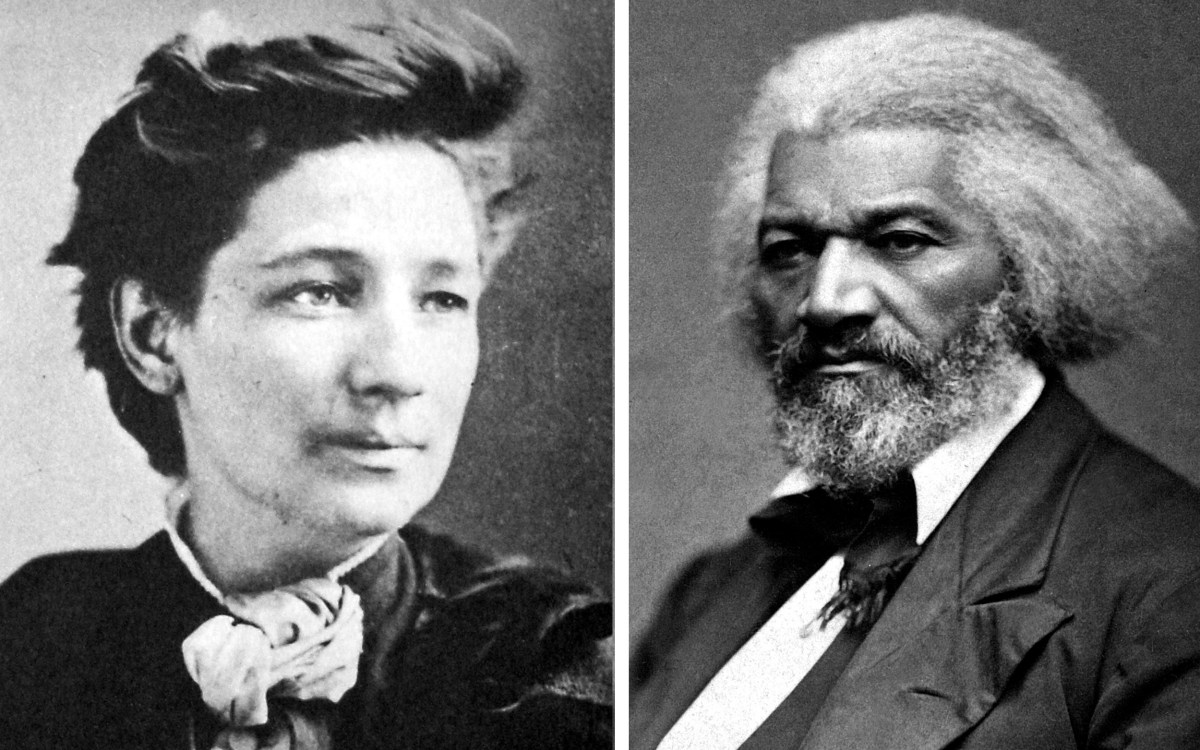

“1867 Douglass” (from Isaac Julien’s film installation “Lessons of the Hour”), 2019, depicts Douglass’ 1867 portrait session with Black photographer J.P. Ball.

Courtesy of the artist, Victoria Miro, and Jessica Silverman, San Francisco. The Douglas Tracy Smith and Dorothy Potter Smith Fund, Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art, Hartford, Conn. © Isaac Julien

Frederick Douglass as 19th-century influencer

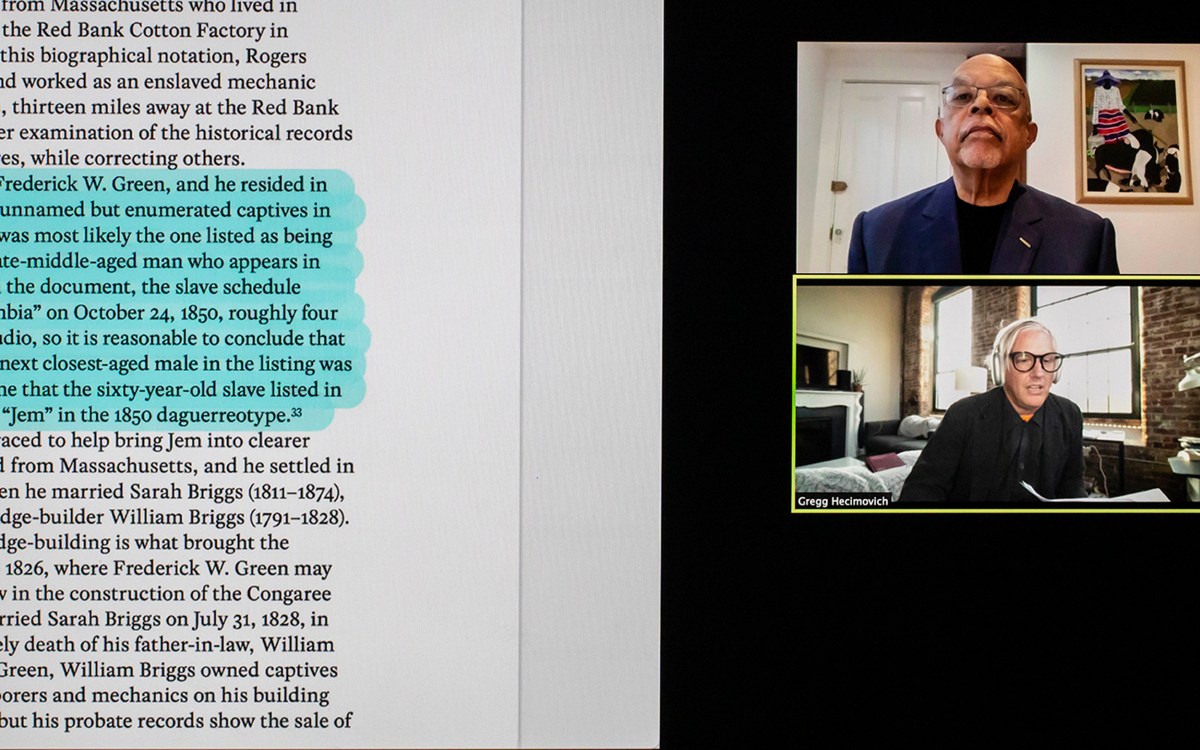

Wadsworth Atheneum show, curated by Sarah Elizabeth Lewis, Skip Gates, explores abolitionist’s embrace of emerging art of photography

HARTFORD, Connecticut — Henry Louis Gates Jr. is an expert on all things Frederick Douglass, having written about the great orator and abolitionist for some four decades.

“I wrote one essay that I really value about Frederick Douglass’ theory of photography and the role of representation in the apparatus of race,” said the Alphonse Fletcher University Professor and Director of Harvard’s Hutchins Center for African & African American Research.

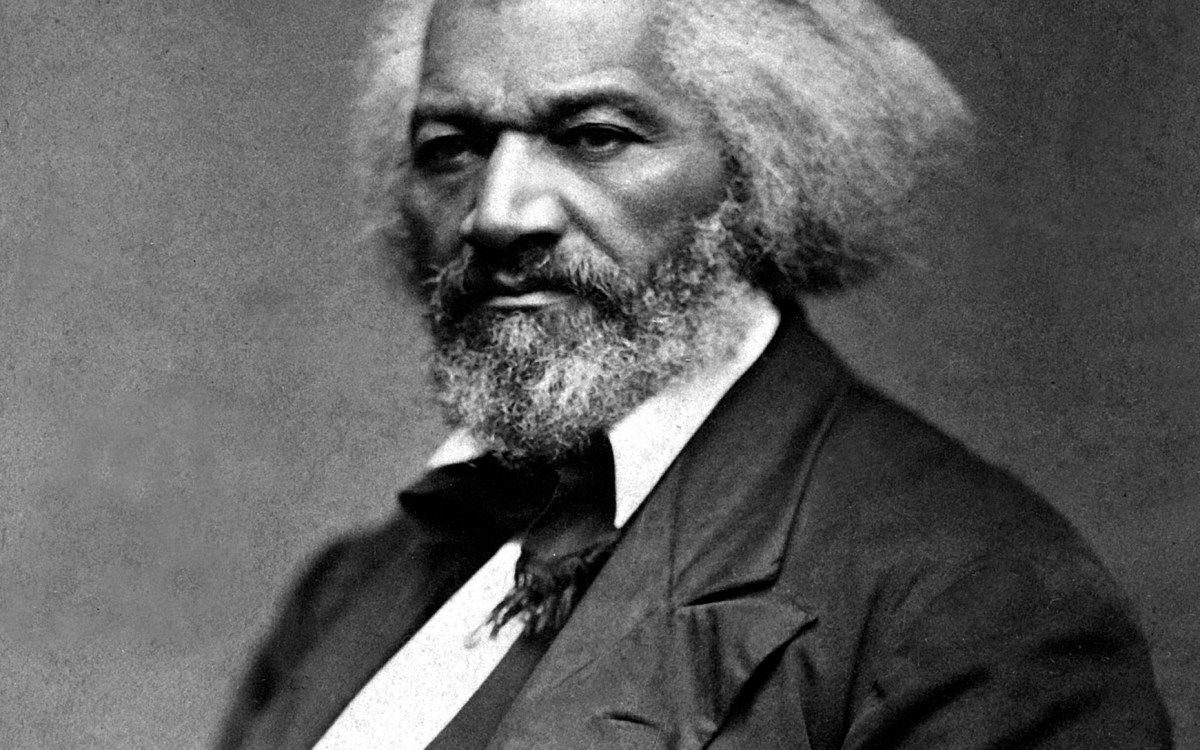

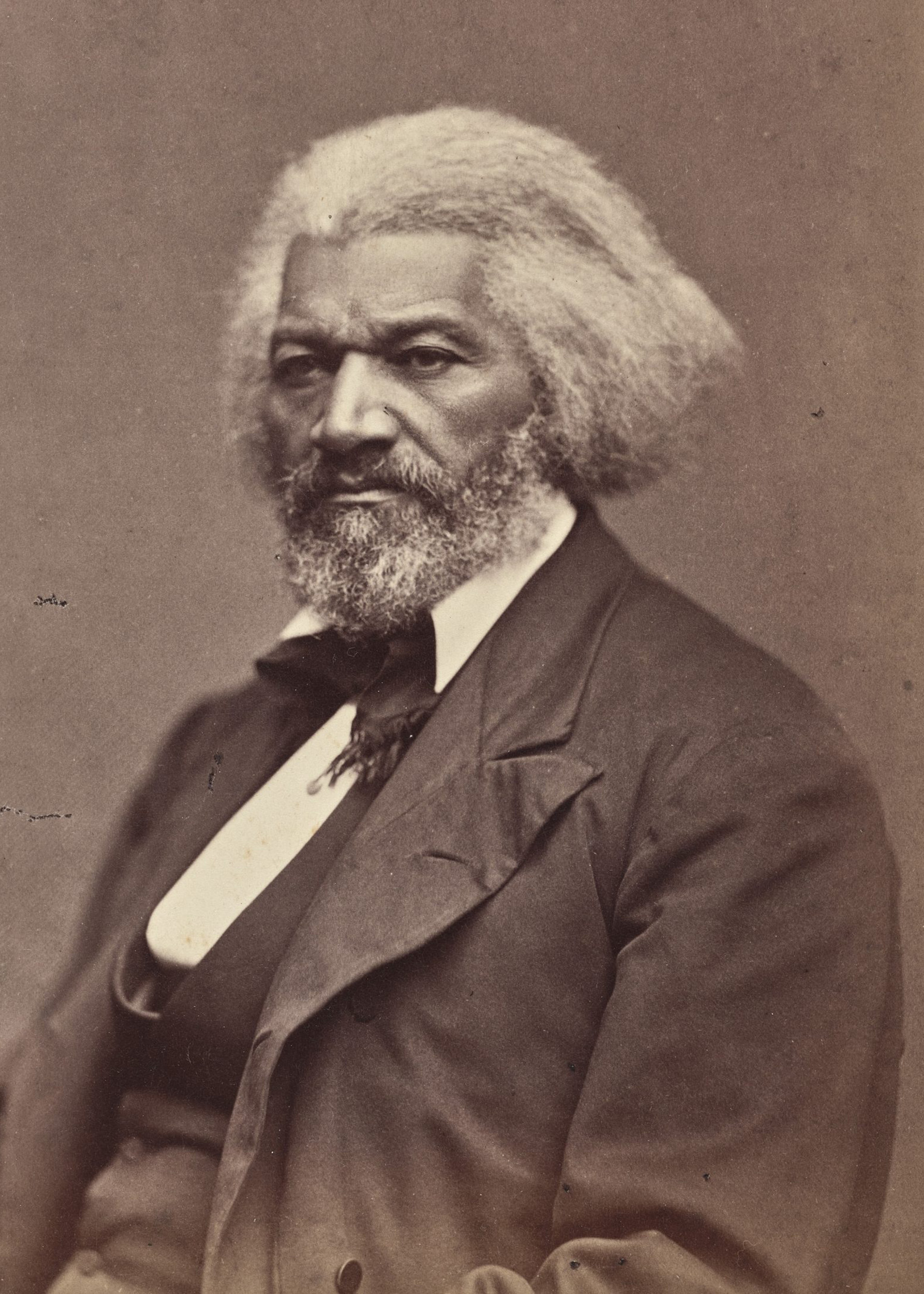

Inviting Gates to curate an exhibition marking the 180th anniversary of Douglass’ first visit to Hartford was a no-brainer for the Wadsworth Atheneum. Museum leadership wanted to pair “Lessons of the Hour,” a film installation by the British artist Isaac Julien, with a selection of portraits featuring Douglass, the most photographed American in the 19th century.

“When I got the email, I thought, ‘Wow, this is something I have the knowledge to do,’” Gates recalled. “I just didn’t have any experience with curating. But I knew someone who did.”

He quickly proposed partnering with colleague Sarah Elizabeth Lewis, the John L. Loeb Associate Professor of the Humanities and associate professor of African and African American studies. “I Am Seen… Therefore, I Am,” co-curated by Gates and Lewis, explores Douglass’ embrace of what was then an emerging art. The exhibition is on view through Sept. 24.

Artist Isaac Julien (from left) with Professors Henry Louis Gates Jr. and Sarah Elizabeth Lewis, who curated the exhibit “I Am Seen… Therefore, I Am.”

Photo by Meka Wilson

“Lessons of the Hour” (2019) anchors the show. The 28-minute work, which takes its title from Douglass’ 1894 speech against lynching, is presented on five screens, each running separate but linked video. It evokes the busy walls of a 19th-century salon, with actors recreating scenes from Douglass’ life — including his 1867 portrait session with J.P. Ball, a Black photographer with one of the most bustling studios in 19th-century America. In an opening night conversation, Julien noted the film was influenced by Gates’ work on Douglass, including his essay for the 2015 book “Picturing Frederick Douglass.”

The film’s lead actor quotes from several of Douglass’ famous speeches, including 1861’s “Lecture on Pictures,” his earliest articulation of photography’s capacity to counter racist stereotypes. “Daguerreotypes, ambrotypes, photographs, and electrotypes, good and bad, now adorn or disfigure all our dwellings,” Douglass says in the film. “Men of all conditions may see themselves as others see them. What was once the exclusive luxury of the rich and great is now within reach of all.”

That speech, delivered in Boston amid the first months of the Civil War, wasn’t what anybody expected, Gates explained on opening night. The audience had thought Douglass would talk about abolition or strategies for defeating the South.

“Instead, they heard, ‘Go to a studio and get your daguerreotype taken.’”

The exhibition includes a handful of the 160 portraits of Douglass known to exist, including this one from 1879, and a selection of pictures of other Black Americans, all taken before 1865. Most of their names are unknown but this circa 1850 portrait is etched with the name of Cornelia Read, who was born free in South Carolina and eventually settled in Dedham, Massachusetts.

The Amistad Center for Art & Culture, Hartford, Conn.; collection of Greg French

Ideas were surfaced that that still resonate more than a century and a half on, offered Lewis, who founded the Vision & Justice civic initiative and has her own catalog of scholarship on Douglass’ theory of image-making. “What is the role of art and culture for justice? What is the role of representation in our representational democracy?”

Both Harvard professors underscored the influence of the Civil War, the first conflict to be widely captured on camera. “Photography was in the air,” Gates said. “And Douglass, with his keen perception, was able to take this floating technology and describe exactly how it can be used to free people.”

Douglass saw that the technology could help Americans grapple with unimaginable horrors, as with the gruesome battle scenes that circulated in the 1860s. “But he also understood its capacity to change the narrative about who counts and who belongs in this country,” Lewis said. “That’s why he put himself in front of the camera so frequently. He knew there was an image he was shattering about Black Americans at the time.”

Complementing Julien’s piece is a digital display of Douglass portraits, a mere handful of the 160 known to exist. But the exhibition’s most poetic turn, conceived by Lewis, is a gallery of pre-Emancipation daguerreotypes of and by Black Americans. Ball isn’t the only successful photographer featured. Also on view are daguerreotypes of a diverse clientele by Augustus Washington, who was based in Hartford in the 1840s and ’50s.

“He knew there was an image he was shattering about Black Americans at the time.”

Sarah Elizabeth Lewis, John L. Loeb Associate Professor of the Humanities and associate professor of African and African American studies

Other displays are stocked with pictures of Black Americans, all taken before ratification of the 13th Amendment in 1865. Each tiny portrait reflects both the singularity and relatability of its subject, some of the very qualities Douglass valued in the medium. There are goofy smiles and confident stares. Several of the men hold musical instruments; one man poses alone with a baby. All images are on loan by Boston-based Greg French, a pre-eminent collector of early photography.

Most of their names are unknown, presented as reminders of the work still needed to know and honor this history. But at the center of the gallery, in a case all to itself, is a tiny portrait taken circa 1850 of the stylishly attired Cornelia Read, who was born free in South Carolina and eventually settled in Dedham, Massachusetts. We know her name because it was etched into the back of the plate. She locks eyes with the viewer assuredly.

Images like these capture the context in which Douglass was working, Lewis said. For Black Americans in the 19th century, photography was far more than a means of self-expression. “It became a tool to exercise one’s rights.”