Alan Diaz/AP Photo

The economy keeps getting better. Our moods? Not so much.

Political polarization a likely driver, policy expert says. For young people, uncertainty around jobs and housing.

U.S. unemployment is close to a 50-year low (3.6 percent), wages grew last month (4.4 percent), exceeding May’s inflation rate for the first time since 2021, and despite a series of interest rate hikes by the Federal Reserve, retail spending is keeping pace with inflation, which slowed to 3 percent in June, down from 9 percent a year ago.

In other words, the economy is strong. And yet, most Americans aren’t feeling it, according to the latest Michigan Consumer Sentiment Index. While sentiment is up 28 percent from a historic low last June, it remains “below historic standards,” the index director wrote, adding: “A majority of consumers still expect difficult times in the economy over the next year.”

Published by University of Michigan researchers, the index is widely seen by economists, politicians, and business leaders as a reliable snapshot of views that influence consumer spending, which accounts for more than two-thirds of the nation’s gross domestic product.

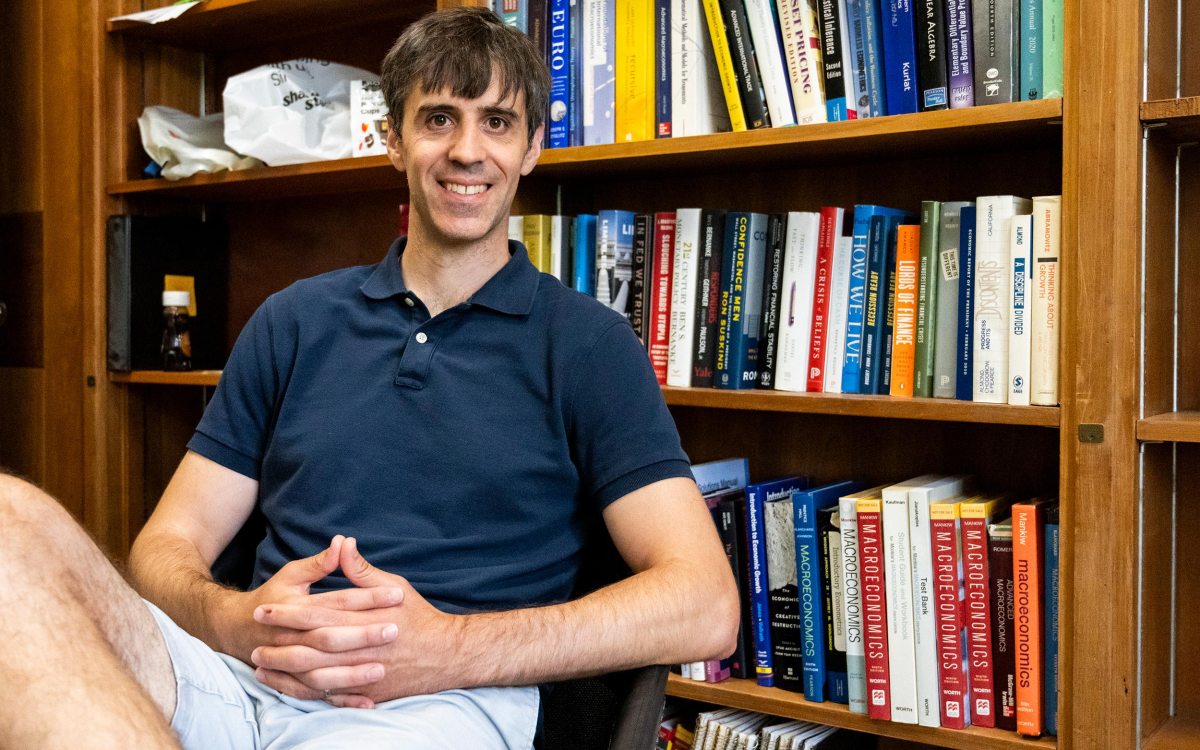

So, what’s driving the disconnect? The Gazette asked Karen Dynan, a professor of the practice of economics and public policy at the Faculty of Arts and Sciences and Harvard Kennedy School, respectively. Dynan served as assistant secretary for economic policy and chief economist at the U.S. Department of the Treasury from 2014 to 2017. The interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Q&A

Karen Dynan

GAZETTE: How would you characterize the state of the economy right now?

DYNAN: I was looking at consumer sentiment numbers just a little while ago. It depends on which index you look at, but some are in the range we saw in the early 2010s, when the economy was really struggling to recover from the financial crisis. Today’s economy is in a very different place. The rate of job openings is running about one-third higher than what we saw just before the pandemic, which was a pretty strong labor market. We are seeing it in the broader economy, as well. People are continuing to spend money as if the economy is in good shape. If you’ve been to an airport recently, you know people are traveling as if there hadn’t been a pandemic at all. You can also see it in the data. Yesterday, we got a retail sales report, and it showed that spending continues to rise at a decent clip.

As someone who has spent a long time in the policy world, I need to caveat this by saying the economy is, of course, not working for everyone. But household finances look quite solid, particularly if you’re looking at how the current situation compares to where we were three years after the financial crisis. We are seeing high levels of wealth; saving is up across the income distribution and delinquency rates and bankruptcy rates remain quite low.

GAZETTE: Why do consumers remain so uneasy about the economy?

DYNAN: One feature of the current situation is that there seems to be a disconnect between how people think they’re doing personally versus how the broader economy is doing. The New York Fed publishes a survey of consumer expectations, and they ask people about their own prospects. If you look at how people say their own income or their own earnings are going to change over the coming year, the figures look as good or better than prior to the pandemic. Similarly, if you look at what people say about the odds of losing their job over the coming year, it looks quite low by historical standards, even though people say they are expecting a rise in overall unemployment.

So, why is there that disconnect? One thing to think about is how things have been affected by the increase in political polarization in our country, and communications from leaders in different parties.

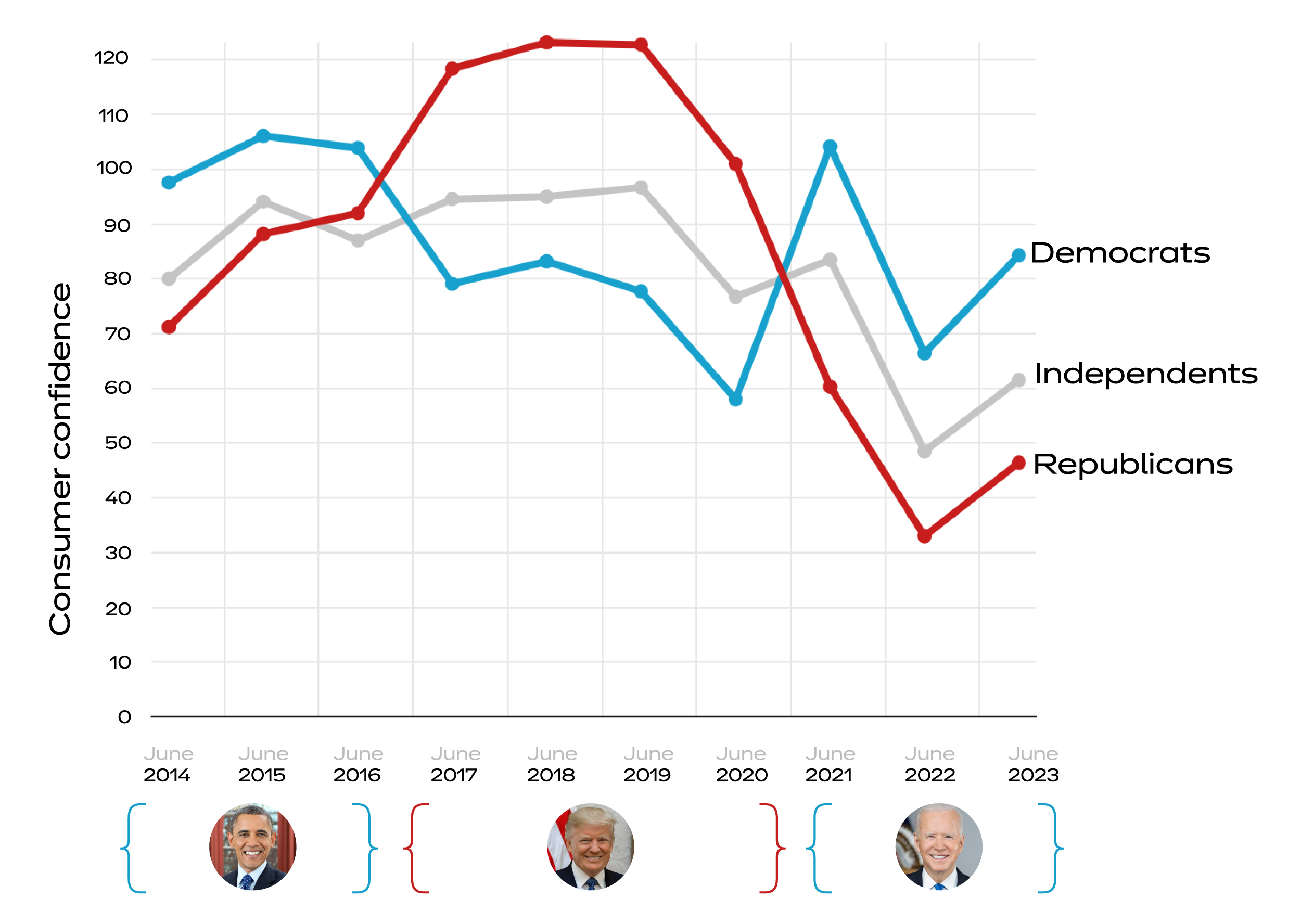

It’s not like sentiment never moves. You can see sentiment moving down for everyone, for example, when the pandemic set in. But there’s a striking gap between people identifying with different political parties. What I found particularly interesting, looking at the data, is just how quickly the pattern flipped. It was noticeably higher for Republicans than Democrats throughout the Trump administration, but then flipped very soon after President Biden was elected and then sentiment for Democrats was noticeably higher than for Republicans. To the extent that there has been a recent improvement in overall sentiment, it looks to have been concentrated among the Democrats. So, the role of what people are hearing from the leaders they trust may be coming into play.

The other thing that may matter is the role of uncertainty. Even though the current state of the economy is quite good overall, there’s still a lot of talk about recession — about the fact that the Fed has had to really tighten financial conditions in order to bring inflation down and how that may cause a recession. People really don’t like that kind of uncertainty, so I think that may be playing a role as well.

Consumer confidence by political affiliation, 2014-2023

GAZETTE: One group that has a particularly bleak outlook for themselves are people ages 18 to 34. Why do you think Gen Z and Millennials anticipate tough times?

DYNAN: As a general matter, when there are layoffs in the economy, one group that tends to see higher layoffs is the group that has less job tenure, so that’s going to be younger people. But that’s probably not the only thing going on. The cost of housing has risen in the last couple of decades, with a particularly sharp increase during the pandemic. That’s been great if you own a home already, but if you don’t own a home yet, you are probably facing higher rental costs, and you are also looking at a higher cost if you plan to buy a home. It’s important to recognize that there have been winners and losers from that situation. I wonder if that’s also on the minds of younger people.

GAZETTE: What effect do consumer fears, justified or not, have on the economy?

DYNAN: That’s something we’ve observed again and again over the years. Recessions can almost be self-fulfilling because suddenly, everybody wakes up and is worried about whether they’re going to lose their job or whether there’s going to be some other disruption to their income that comes from a weak economy. If everyone suddenly believes that the economy is likely to weaken in the future, then they tend to cut back on their spending. So far, we really haven’t seen people cutting back. I would expect them to start cutting back more if we start to see higher rates of job loss with cutbacks both among people who are losing their jobs and suffering income losses, and by other people saying, “Maybe the odds of me losing my job are higher, and so, I should be doing some more saving so that I have a bit of a buffer in case that happens.” This is something policymakers are always worried about: causing a self-fulfilling recession by talking down prospects for the economy.