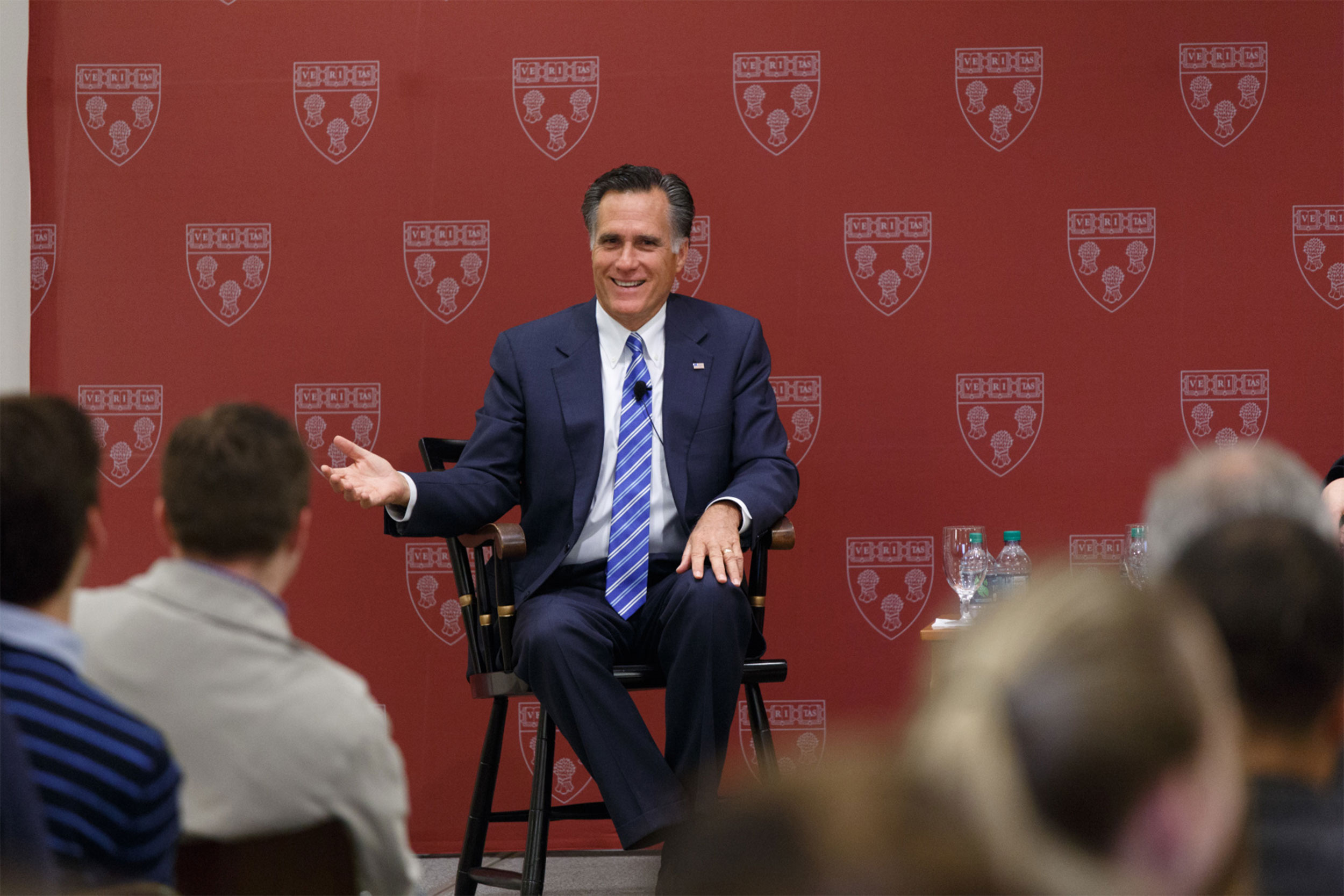

Mitt Romney speaking at Harvard Law School in 2015.

Credit: Heratch Photography

How Mitt Romney found himself alone in Republican Party

New book traces path of scion of prominent GOP family from Harvard M.B.A. to Bain & Co., Mass. State House, U.S. Senate amid rise of Trump

Mitt Romney has made no secret of his disapproval of the far-right takeover of his party.

Romney, J.D./M.B.A. ’75, who just announced he would not seek re-election to the Senate next year, was the only Republican to vote twice to impeach former President Donald Trump. He also denounced Trump over his push to deny the 2020 election results and blamed him for inciting the Jan. 6 insurrection.

In a revealing new book, “Romney: A Reckoning,” McKay Coppins plumbs Romney’s soul-searching struggle to come to terms with the far-right shift of the party and how his public rejection of Trump left the former Republican governor of Massachusetts and presidential candidate feeling disillusioned and politically alone.

Coppins spoke with the Gazette about Romney’s slow recognition that he wouldn’t be able to turn around the party as he once did companies as a Bain Capital consultant. The interview has been edited for clarity and length.

Q&A

McKay Coppins

GAZETTE: Romney is known as a very cautious, straightlaced politician. He’s not a salty, mercurial character like the late John McCain, whom the press loved to cover. What sparked your interest in writing about him?

COPPINS: I had gotten to know him covering his presidential campaign and profiling him for The Atlantic, but I could sense after Jan. 6, when he narrowly escaped the mob and saw the leaders of his party instigate what he considered an insurrection, he really seemed like he was in a soul-searching mood. He was asking himself difficult questions about what his party had become, what was happening to the country, and about his own career.

As a writer, that’s kind of the perfect subject — somebody who is openly entertaining difficult questions — and so, I pitched him on doing this book. I did tell him I only wanted to do it if he was ready to be fully candid because he has this reputation as being so careful and so disciplined and constrained by consultants and talking points. And to my pleasant surprise, he accepted my terms and went for it.

I discovered pretty quickly he does have a more puckish side to him. He has this irreverent sense of humor; he understands how absurd political life can be; and he can even be a little dishy — that’s part of why there’s so much great material in the book.

GAZETTE: In the book, you say his recognition and processing of what’s happened to the Republican party was “halting and messy.” Is that his reckoning?

COPPINS: I think that this process of coming to terms with his own role in the Republican Party, and what the party now stands for, was hard for him. There were some meetings where he would openly muse about leaving the Republican Party, and then the next meeting, he would walk that back and say, “Well, I’m not a liberal,” and then, the next meeting, he would muse aloud about some of the compromises he had made. He would be a little bit more defensive. There’s something very human about that. There’s not a straight line toward enlightenment. That takes a lot of hard work.

I’m not a therapist, but it often seemed almost therapeutic, these conversations, for him. We had almost 50 interviews over the course of two years, and I do think he went on kind of a journey during that period to the point where, in the last interview we did for the book, he was telling me that he was looking into officially leaving the Republican Party and starting a third party. I think by the end of those two years, he had come to terms with the fact that he doesn’t have a home in the GOP anymore.

GAZETTE: Behind the scenes, Romney was much more active trying to derail Trump than was previously known. As Trump started surging in 2016, he entertained getting in the race at the last minute. He met with Michael Bloomberg, the billionaire former New York City mayor, to discuss running together as a spoiler independent ticket, and he lobbied other GOP primary candidates, Sens. Ted Cruz and Marco Rubio, and Ohio Gov. John Kasich, to join forces with him to deny Trump delegates at the convention.

COPPINS: He did a lot. I didn’t know until I got my hands on his emails from that period how much work he was doing behind the scenes to deprive Trump of the delegates that he needed to clinch the nomination.

The problem he kept running into was that all these candidates, Ted Cruz, Marco Rubio, John Kasich, were too self-interested. They were too consumed with short-term thinking. All of them would tell him, “Donald Trump is a menace. It would be cataclysmic for the country if he won.” But none of them were willing to give up even a modicum of short-term political advantage to stop him, and it just drove Romney insane.

The meeting with Bloomberg was in [Jan.] 2016; he had a call from Oprah ahead of 2020 about possibly running. I think if Romney thought that running an independent bid would stop Trump from becoming president, he would have done it in a second. He didn’t think he could actually win as an independent, but he wanted to do it. It’s just that the data he looked at convinced him that he would end up helping Trump and taking votes away from the Democratic candidate. And so, that’s why he stayed on the sidelines. You can tell he was just champing at the bit to get in the race.

GAZETTE: His need to run toward a crisis is called “the Romney obligation” by the family. Did he see himself as someone uniquely qualified to swoop in and save the day? Was that what he was hoping to do when he first headed to Washington as a senator?

COPPINS: He does have an enormous amount of confidence in his own ability to fix things. It’s part of why he struggled as a presidential candidate — because he didn’t have an overarching philosophical vision that he was trying to sell to the country. The vision that he had was just his own pragmatic, technocratic ability to solve problems.

When he came to the Senate, he thought he could fix the Republican Party. He thought he could steer it back toward a traditional Republicanism that he identified with. [His late father, George Romney, was a successful auto executive, former Michigan governor, Nixon Cabinet secretary, and GOP presidential candidate in 1968.] Once he got to the Senate, he realized that the institution itself was much more dysfunctional than he realized and that his party had a depth of cynicism and hypocrisy that he wasn’t prepared for, and by earlier this year, he had realized that sticking around for another term probably wasn’t going to change that.

I would not be surprised to see him play a role somehow in the 2024 race. I think he actively wants to do everything he can to stop Donald Trump from returning to the White House. I don’t know what that’ll look like. Some people wonder if he’ll endorse Joe Biden; some people wonder if he’ll launch some kind of spoiler bid for the presidency. I think he just wants to see how he can be useful in that project.

“I would not be surprised to see him play a role somehow in the 2024 race. I think he actively wants to do everything he can to stop Donald Trump from returning to the White House.”

GAZETTE: Former President George W. Bush, who was at the Business School when Romney was here getting a J.D./M.B.A., says in the book, “At Harvard, there’s a lot of people who believe the word ‘Harvard’ entitles them to think they’re smarter than everybody else. Mitt Romney was not that way.” Talk about his Harvard experience — it was different than most of his peers’.

COPPINS: He was in a totally different point of life when he arrived at Harvard. He was married; he had kids. They lived in Belmont, where he was living this traditional suburban life. He really didn’t get there thinking that he was this brilliant intellectual force. He had been a fine, but not star student when he was in high school. He felt like he had to put in extremely long hours studying so that he could keep up with everyone else, and he didn’t have a big social life on campus because he had his wife and kids.

I think that he saw Harvard as a platform to realize his newfound ambition, which really arrived for him after his Mormon mission. He got home from his mission and decided he wanted to lead a serious life, which had not always been apparent to him.

GAZETTE: One misconception that dogged Romney was that he couldn’t possibly be as earnest and wholesome as he, in reality, was. “I’m the authentic person who seems inauthentic,” he said. And that became a political albatross for him.

COPPINS: I think it was very frustrating for him that even when he was just being himself, showing affection for his wife or cracking silly jokes, people assumed that it was a phony put-on. And it wasn’t, but he didn’t know how to communicate the way he was authentically. It was something even more frustrating for his family, who felt like the caricature of him in the media just didn’t match at all the person that they knew.

But I will also say that this was a failure of his presidential campaigns in some ways. They kept him on a very short leash: They didn’t really want him ever talking about his religion, which was central to his identity, and to be really careful about how he talked about his business career because that was also a liability in its own way. So you’re taking two of the central components of his life off the table and you’re left with this shell of a presidential candidate who doesn’t seem like a real person and allow your opponents to define you. And I think that’s what happened to him.

GAZETTE: Why is he leaving the stage in such dramatic fashion? Some say he’s hoping to rewrite his political legacy.

COPPINS: Yes, I think he’s thinking about his legacy. I think he’s thinking about what his obituary will say, what the history books will say about him. And I think we would be better off as a country if more elected leaders were thinking that way.

I asked him early on, are there any lessons that you’d like future political leaders to take from your story? And he said, “I wish that more of us, including myself, were able to think about how we will be remembered when we’re gone instead of just how our decisions will play in the next news cycle or the next election cycle.”

And so, you can ding him for trying to rewrite his legacy, but if that was the thing that prompted him to finally prioritize doing what was right over doing what was politically convenient, I think that it’s a good thing, and we should expect it from more of our political leaders.

Coppins will speak about the book at the Cambridge Public Library on Monday, Oct. 30, 6 p.m., in a free event sponsored by Harvard Book Store.