Greek grave stele of a woman dying in childbirth, c. 330 BCE.

© President and Fellows of Harvard College; Courtesy of the Harvard Art Museums

What radiologists can learn from looking at art

Medical humanities program inspires exhibit that rewards critical viewing

It’s essential that radiologists develop a critical — and empathetic — eye to inspect X-rays, CT scans, and other medical images. Could an arts program help sharpen those skills?

That question sparked the Seeing in Art and Medical Imaging program — a partnership between the Art Museums and Department of Radiology at Brigham and Women’s Hospital — now in its sixth year.

It’s also the subject of an exhibition on view at the Art Museums through the end of the month that allows the public to explore the same questions as medical residents.

“This is the first time that we have ever had an exhibition at the museum that is about a curricular collaboration,” said Jen Thum, co-curator of the exhibition and a program instructor. “It’s showing people how radiologists work and giving them a chance to think about the same kinds of big issues.”

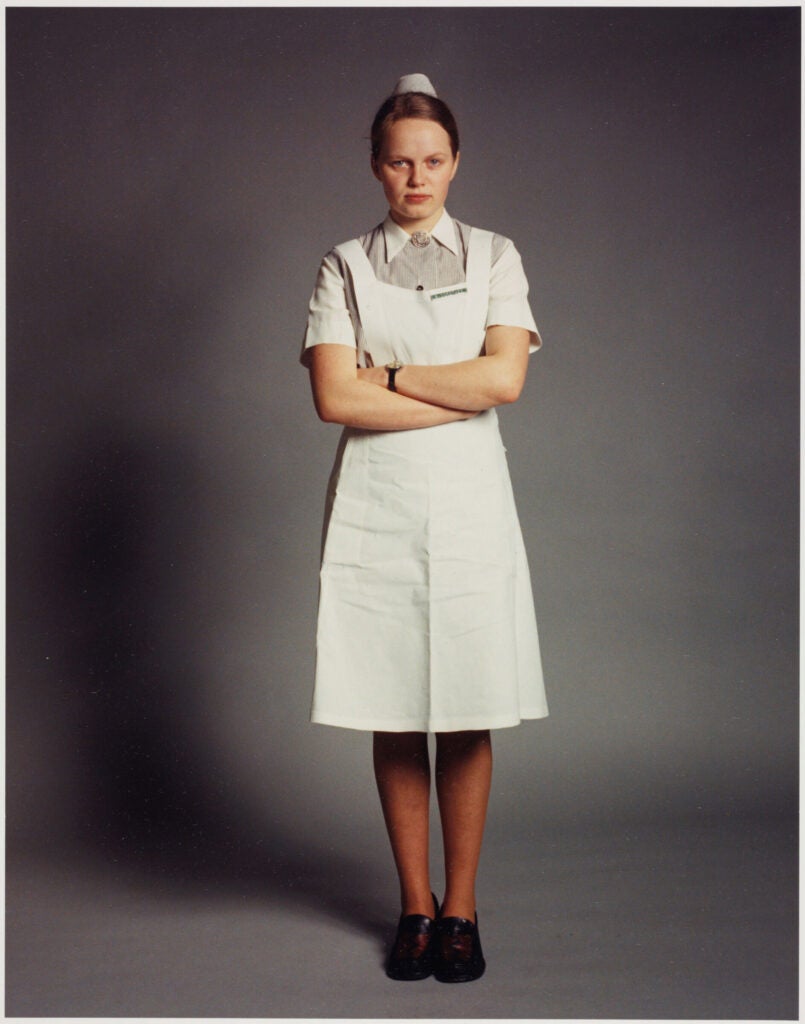

“Dorothee Oppermann, 20, Nursing Student,” 1974.

“Shutter (c)” by Rosemarie Trockel, 2006.

“Available Portrait Colors” by Annette Lemieux, 1990.

© President and Fellows of Harvard College; Courtesy of the Harvard Art Museums

Hyewon Hyun, a Brigham and Women’s radiologist and co-founder of the program, felt that residents would benefit from interdisciplinary learning. The yearlong program focuses on the “human-to-human” connection, a vital part of working both in hospitals and with art.

“In order to take care of patients, I would want that physician to be as compassionate and as understanding and as human as possible,” Hyun said.

Through the program — and now the exhibit — art is the starting point for in-depth conversations about medicine, humanity, and different ways of seeing the world. It gives residents space and permission to sharpen their observation skills in a low-stakes environment.

“Radiologists, for their entire working lives, are looking at images, which is exactly what I do,” said Thum of her role as an art curator. “But we do it at a different pace. So we slow down; we can remove the residents from the hierarchy of the hospital … it’s a permission to do things that they can’t do in the hospital.”

Residents explore seven themes: narrative, objectivity, embodiment, empathy, power, ambiguity, and care. Each plays an important role in the relationships of medical professionals and their patients.

“We know that from data that medical students kind of lose their empathy for patients,” Hyun said. It can be a lot of pressure to work in a fast-paced hospital setting; removing residents from this environment gives them space to explore their own humanity.

Take the sculpture “Shutter (c)” by artist Rosemarie Trockel. In the red-glazed stoneware, people see all sorts of things, Thum explains. As viewers interact with the sculpture, they may see a window, raw meat, ribs, or other objects.

“It’s very different for a radiologist — versus what happens to them in the reading room — to have multiple, equally valid readings of an image that are very different from each other at one time,” Thum said. “Or for there not to be a single correct answer, or no answer at all. That ambiguity can be kind of uncomfortable, but it’s very productive.”

The installation is on view through Dec. 30.

© President and Fellows of Harvard College; courtesy of the Harvard Art Museums

Thum said while the exhibit was born out of the Seeing in Art and Medical Imaging program, she believes it will appeal to more than just medical professionals.

“Most visitors to an art museum don’t slow down either,” Thum said. “You don’t have to be a doctor to engage in the space and to consider these questions.”

For Hyun, her hope is that visitors will consider the connection between medicine and art in a new way.

“For young people, I’m really hoping that they would see that there is not this divisiveness between the humanities and medicine that they think there is, because that’s an artificial division that has been developed over decades,” she said. “But in order to be a good physician for a long period of time … you need to nurture the other side, the humanity side.”

Harvard Art Museums are free and open to the public. Seeing in Art and Medicine is located in the University Research Gallery through Dec. 30.