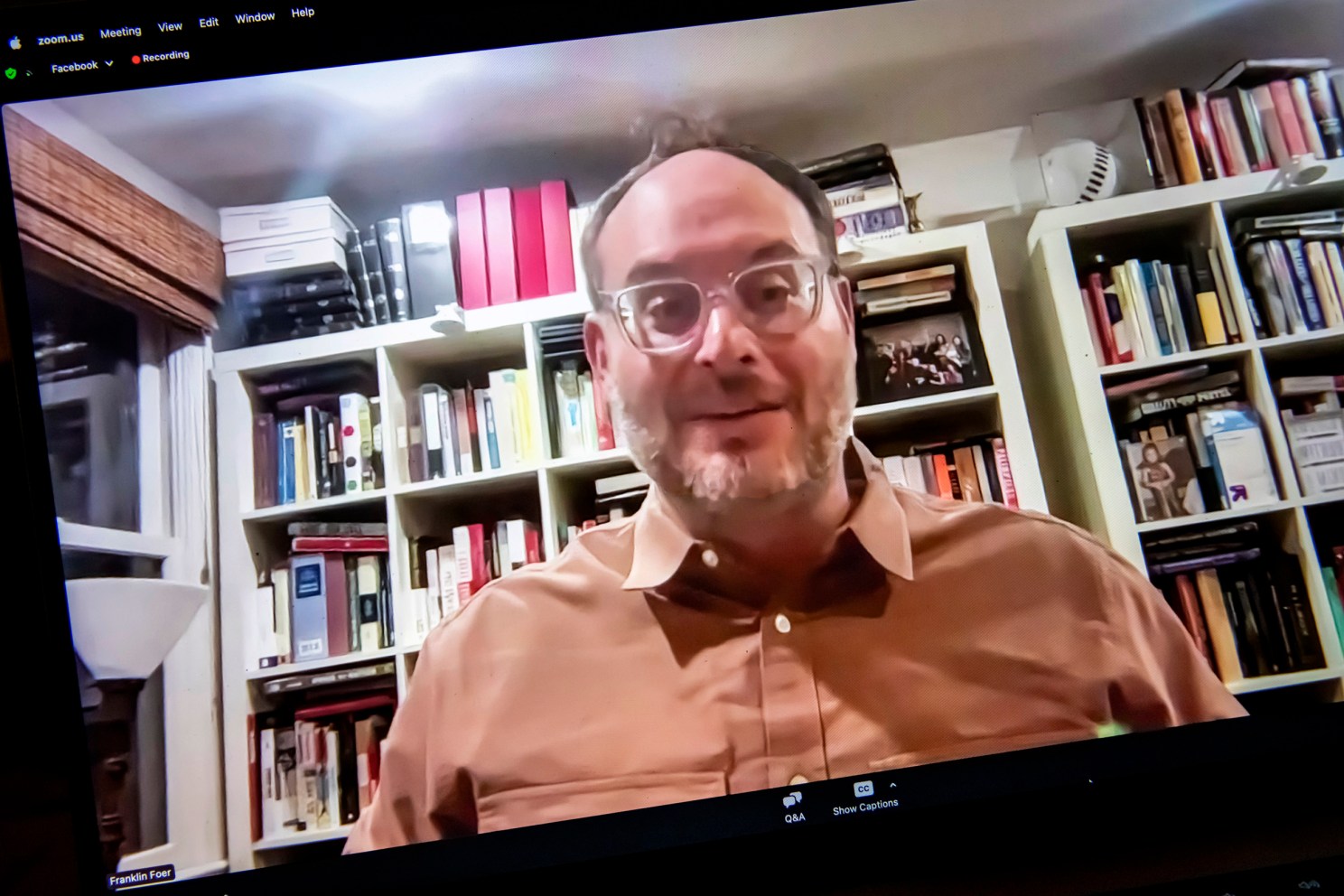

Staff writer for The Atlantic Franklin Foer in an online discussion.

Jon Chase/Harvard Staff Photographer

Decline of golden age for American Jews

Franklin Foer recounts receding antisemitism of past 100 years, recent signs of resurgence of hate, historical pattern of scapegoating

The golden age for American Jews is in decline. At least, for now.

That was the provocative proposition put forth in journalist Franklin Foer’s cover story for the April issue of The Atlantic. It was also the topic of an online discussion with the magazine’s staff writer Thursday night sponsored by Harvard Hillel.

Introduced by Dani Passow, rabbi and educator at Harvard Hillel, Foer jumped right into the history of Jews in America, noting the rise and apparent fall of antisemitism in the last century.

He recalled how as recently as the 1940s, “there was still this incredible amount of antisemitism in the United States. At institutions, including Harvard, there were quotas.”

While some Jews had obtained power in various industries, he explained, they were still a minority. “Jews existed on the fringe of the elite,” he said. “But there was a Protestant monopoly that was preventing them from having full access.”

However, he continued, within 10 years — following the exposure of the horrors of Holocaust — antisemitism seemed to be in retreat. “In 1950, I think, there was not a single Jewish professor at Yale,” he recalled. “And by the end of the 1960s, 17 percent of the professors at elite universities were Jewish, which is an incredible change over a short period of time.”

Franklin Foer

“Jews didn’t have to accept the devil’s bargain [where] the cost of citizenship was assimilation. In the United States, you could be your Jewish self.”

What followed, he said, was a golden age for American Jewry. Unlike in Europe, “Jews didn’t have to accept the devil’s bargain [where] the cost of citizenship was assimilation. In the United States, you could be your Jewish self.” He described the decades that followed as feeling like a “bear hug.”

“It felt like for a period where the nation wrapped its arms around you,” he said. With a few exceptions, such as ex-Klansman David Duke’s campaign in Louisiana and statements associated with the Nation of Islam, “when I was a college-age kid in the 1990s, I felt like antisemitism had completely disappeared,” Foer said.

Soon after, however, things changed. “It took me a while to accept the fact that this golden age was in decline,” said Foer. His investigation began before the Hamas attack of Oct. 7, he said, sparked by a call from his brother, whom he described as more observant. The brother, who was wearing a yarmulke, related having someone follow him down a street in Brookline muttering “Trump, Trump, Trump.”

As he began researching “the long arc of American Jewish history,” what he found was an old story. Following 9/11, “a rolling series of crises” had each brought an uptick in antisemitism.

“When things [happen] that are difficult to comprehend, like a pandemic, people begin searching for something to blame,” he explained. As happened in Europe during the Middle Ages when the Black Plague hit, that “something” was the Jews.

“People may not even realize that they have this reservoir of narratives. But when events happen, Jews get depicted as the villains.” He cited Trump’s disparagement of former Goldman Sachs CEO Lloyd Blankfein and philanthropist George Soros. Once such antisemitism became acceptable, he said, “it started pouring out.”

At that point, Passow raised a point from Foer’s article, asking what form contemporary antisemitism assumes on either side of the political spectrum.

From the right, Foer said, it takes the form of the so-called great replacement theory, whose adherents believe Jews are conspiring with Black and brown people to replace white Christians. In this theory, he said, Jews “are agents who can pass in white society but are seen as doing the bidding of Black and brown people.” For example, “George Soros getting blamed for the ‘invasion’ on the Southern border.”

On the left, he continued, it takes a different form. “Increasingly it’s integrally tied up in debates about Israel” and the war in Gaza.

“There are very non-antisemitic ways to criticize the state of Israel,” he pointed out. “Much of American Jewry is very critical of Israeli policy.”

Still, he continued, there is a strain of anti-Zionism that utilizes ancient tropes to blame Jews, reviving the myth of a cabal of Jews more loyal to Israel than to America. “It alleges that American Jews are manipulating American foreign policy; they’re manipulating American universities.”

Franklin Foer

“There were certain ideas that Jews played a role in championing and helped to develop. One of these we can broadly describe as liberalism: There was cultural pluralism; there were ideas about tolerance. There were ideas about the universal protection of minority rights

and civil liberties.”

This trope also calls into play “one of the classical elements of antisemitism,” said Foer: “This notion that Jews are bloodthirsty.”

As the evening wound to a close, Passow asked Foer about any findings that didn’t make it into his article but should have. Foer responded the intensive editing and fact-checking process had driven any such thoughts from his mind, but he did share one observation.

“A lot of my piece is about the things that enabled the golden age of American Jewry,” he said. “There were certain ideas that Jews played a role in championing and helped to develop. One of these we can broadly describe as liberalism: There was cultural pluralism; there were ideas about tolerance. There were ideas about the universal protection of minority rights and civil liberties.

“Jews embraced those because they were good for America, but they were also good for Jews. And so as the golden age has gone into this period of decline, what we see is that it’s just a symptom of a democratic culture and of institutions that have abandoned the liberalism that made the golden age possible.

“So I think the thing that would most help American Jewry and reverse this climate is if we could restore democratic culture to the country, if we could dispense with some of the worst parts of liberalism that didn’t actually work, but save and preserve the soul of liberalism as the guiding ethos of American institutions and of our society.”