Climate expert Michael Mann from the University of Pennsylvania.

Elizabeth Hanlon/Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs

Forget ‘doomers.’ Warming can be stopped, top climate scientist says

Michael Mann points to prehistoric catastrophes, modern environmental victories

Keeping the Earth’s warming below the 1.5-degree Celsius threshold that scientists believe will stave off climate change’s worst effects is a tall task, but one of the world’s top climate scientists believes climate “doomism” won’t help the fight. And Michael Mann is all about the fight.

“I push back on doomism because I don’t think it’s justified by the science, and I think it potentially leads us down a path of inaction,” said Mann during a talk last Thursday at the Harvard Kennedy School’s Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs. “And there are bad actors today who are fanning the flames of climate doomism because they understand that it takes those who are most likely to be on the front lines, advocating for change, and pushes them to the sidelines, which is where polluters and petrostates want them.”

“I push back on doomism because I don’t think it’s justified by the science, and I think it potentially leads us down a path of inaction.”

Michael Mann

One recent victory for the University of Pennsylvania professor stems back to 2012, when climate change deniers and critics of his work wrote blog posts accusing him of scientific fraud. Mann demanded retractions. They refused, and he sued them for defamation. The case dragged on for years, but in February, Mann won $1,000 in punitive damages from one blogger and $1 million from the second.

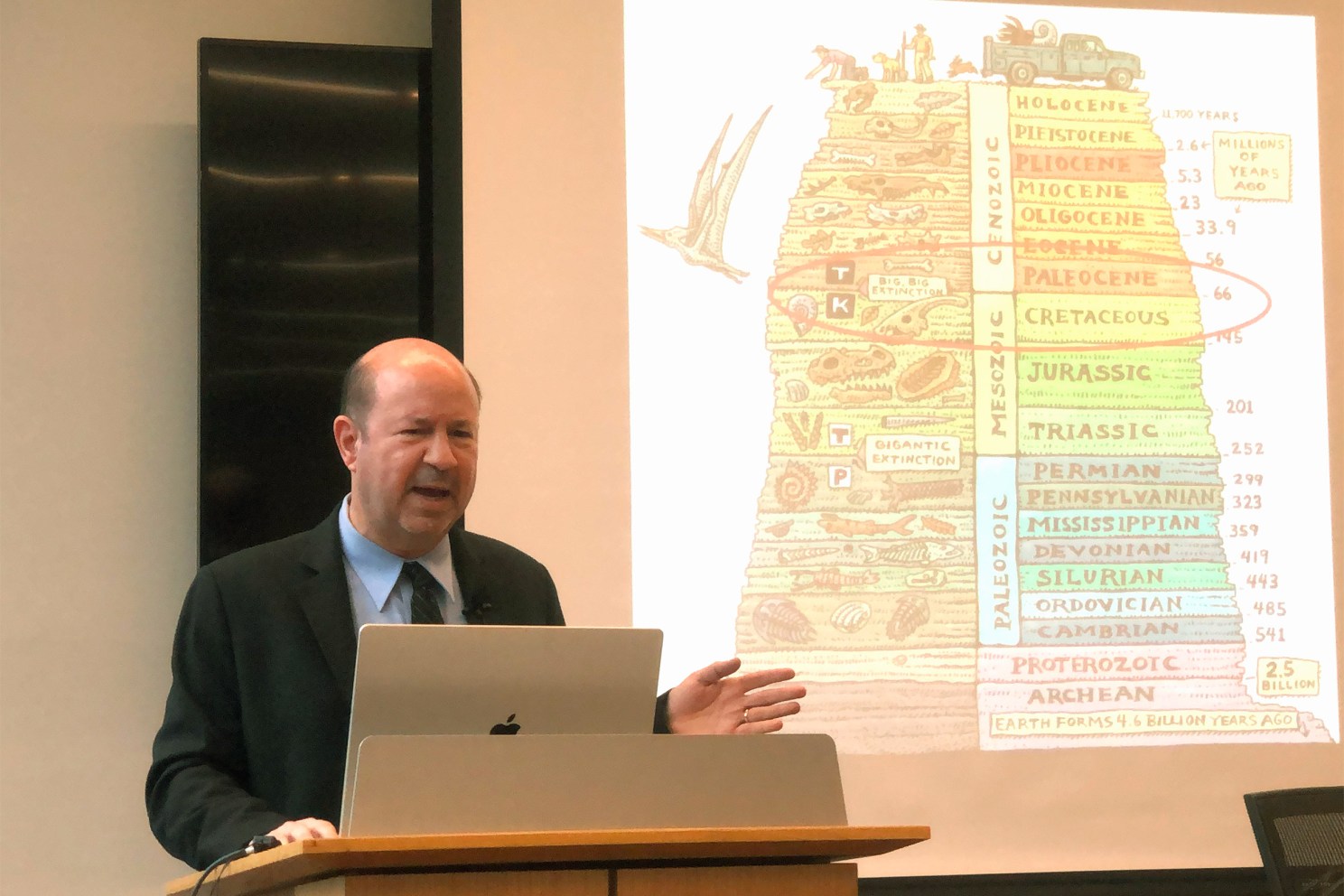

Mann’s lecture, “Can Lessons from Earth’s Past Help Us Survive Our Current Climate Crisis?,” sought lessons from past climate change events in the Earth’s history, encompassing the demise of non-avian dinosaurs, the “Great Dying” 250 million years ago, pop musicians The Police — who sang of doomed dinosaurs — and famed astronomer Carl Sagan.

Mann, whose most recent book, “Our Fragile Moment,” was published in September, said the demise of the dinosaurs offers an example of the potentially deadly impact of climate change — in that case, from global cooling.

It is believed that a comet struck the Earth 65 million years ago, resulting in the death of non-avian dinosaurs. Most of them were not killed by the strike itself, but the drop in temperature caused by the rise of dust from the impact, which blocked the sun.

Small mammals, able to shelter in burrows, did survive, beginning an evolutionary process that would lead to humans. Sagan, the late scientist and science communicator, warned of a similar effect in the event of global nuclear war, which would likely bring on “nuclear winter” severe enough to bring on an extinction event.

Mann also discussed the “Great Dying,” which killed some 90 percent of species. It took place at a time when the Earth’s temperature spiked relatively suddenly in geologic terms. He said it was likely brought on by carbon dioxide being released in a major outbreak of volcanism that stretched thousands of years.

The current human-induced climate change has parallels to that time but is occurring much more rapidly, over tens of years rather than thousands.

“Warming today is hundreds of times faster than any warming in geological history,” Mann said, adding that the direction of the temperature swing — warmer or cooler — doesn’t matter. “Anything that takes you from the climate you’re adapted to is a threat.”

Mann’s work brought that point home back in 1999, when he and colleagues published a reconstruction of climate for the past 1,000 years. They used statistical methods they’d devised to combine climate proxies like ancient tree ring data, ice cores, and lake sediment into a single picture of the Earth’s climate history.

Represented graphically, the global mean temperature data resembled a hockey stick, with centuries of slowly declining temperatures making up the long handle and the sharp uptick in temperatures since the Industrial Revolution making up the blade. That “hockey stick” graph has since been hailed as evidence that the recent decades’ warming is neither natural nor a figment of scientists’ imagination.

During the event, Mann said the “Great Dying” era offers other lessons because it has been theorized that the warming was due to a major release of methane from the ocean, and some climate pessimists, whom he called “doomers,” believe a similar dynamic is already at work today, at least partly due to thawing of the arctic permafrost. In fact, he said they believe that enough methane has been released that it is already too late to avoid extinction-level warming.

Mann rebuts this view, noting it is inconsistent with the latest scientific understanding of the ancient event as well as evidence about today’s situation. And it serves as a distraction at a time when urgent action is needed.

Many have noted the already-existing anxiety about climate change inaction among today’s youth. Mann said in the interview during his campus visit that he would hope examples of the past will energize them rather than make them feel helpless.

Younger people today, he said, haven’t lived through high-profile environmental crises of the past, such as water pollution like that of Cleveland’s Cuyahoga River, once so full of industrial pollutants it periodically caught fire; power plant emissions, which created acid rain that damaged downwind forests and made lakes acidic; and the creation of a massive hole in the Earth’s protective ozone layer, which threatened to raise cancer rates around the Southern Hemisphere.

Each of those problems, while not on the scale of climate change, was analyzed by scientists and solved by policy: the Clean Water Act, the Clean Air Act, and the international Montreal Protocol.

Mann’s talk wassponsored by the Belfer Center’s Environment and Natural Resources Program and its Arctic Initiative; the Shorenstein Center on Media, Politics and Public Policy; the Salata Institute for Climate and Sustainability, and the HKS Climate, Energy, & Environment Professional Interest Council.

It was introduced by Henry Lee, director of the Environment and Natural Resources Program, and by Shorenstein Center senior fellow Cristine Russell, who engaged Mann in a question and answer session after his talk.

Mann noted that a difficult road lies ahead, but there is time still to limit warming to 1.5 degrees C. He cited as encouraging the U.S. passage of the Inflation Reduction Act — which contains significant provisions to fight climate change — and the global agreement in 2021’s COP 26, whose commitments, if enacted, would limit warming to 2 degrees C, which Mann acknowledged is still too high.

“It’s not too late for us to take the actions to keep warming below 1.5 Celsius. The obstacles at this point aren’t physical, they are not technological, they are entirely political,” he said. “And political obstacles can be overcome.”