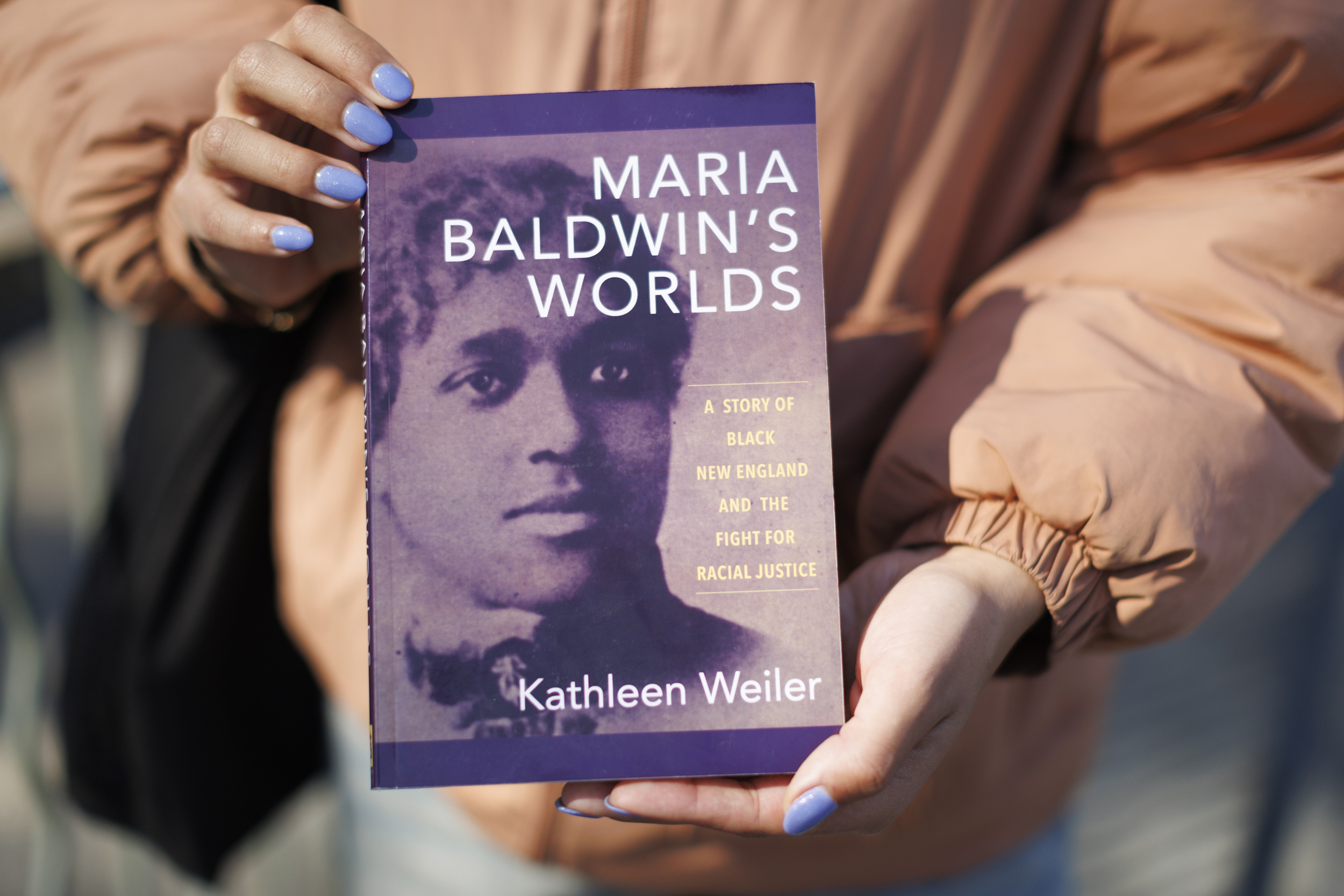

As a high school student, Maya Counter ’24 led the effort to rename the residential Cambridge neighborhood where she grew up from Agassiz to Baldwin. She is pictured outside her elementary school, named after educator and civic leader Maria L. Baldwin, the first Black school principal in the Northeast.

Photos by Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

Renaming of a neighborhood

For Maya Counter ’24, honoring a notable Black educator, and setting right a historical wrong

Maya Counter ’24 was only an infant when her neighborhood school in Cambridge was renamed from the Agassiz School to the Baldwin School. This moment would later take on untold significance for her in high school and later at Harvard where she graduates this month.

In 2002, the Cambridge School Committee voted unanimously to shed Louis Agassiz’s name and legacy of racist ideology from the elementary school and replace it with that of Maria L. Baldwin, honoring the school’s first Black principal who led the school starting in 1889.

Growing up on Sacramento Street, the very street where the Baldwin School is located — “It is like a little heart of Cambridge”— Counter always felt connected to the school’s namesake, who was celebrated throughout the halls on posters and plaques.

“She was an incredible person, a civic leader, and awesome person within the community,” Counter said.

Baldwin was born in Cambridge in 1856, attending public schools that were racially integrated (codified by Massachusetts law in 1855). She graduated from Cambridge High School in 1874, earned a teaching certificate in 1875, and in 1881, she secured a full-time position at the Agassiz School, then a predominantly white, middle-class school, becoming the only Black teacher in Cambridge. Within eight years, she was recommended to replace the retiring principal of the Agassiz, making her the first Black principal in Massachusetts and the Northeast.

“Baldwin was remembered by students and colleagues for her quiet authority, her love of literature and poetry, and her affection for and nurturing of her pupils,” Beth Folsom, program manager for History Cambridge (formerly the Cambridge Historical Society), wrote in 2021.

Among the children Baldwin educated was Edward Estlin Cummings, who famously grew up to become the notable American poet e.e. cummings. He reflected nearly 60 years later on his beloved principal “blessed with a delicious voice, charming manners, and a deep understanding of children.” “Never did any semidivine dictator more gracefully and easily rule a more unruly and less graceful populace,” and “from her I marvellingly learned that the truest power is gentleness,” he wrote.

Despite the school’s renaming, the Agassiz neighborhood name remained. Counter recalled her early unease, “When I was old enough to understand why my elementary school name changed, I started questioning why the Agassiz neighborhood was still named the Agassiz neighborhood. And then learning more about how he used science to classify Black people as inferior, I felt almost awkward being a Black person walking around the neighborhood I love. Thinking about that name representing me in the community, it just didn’t sit right with me.”

By the time Counter was at Cambridge Rindge and Latin High School and studying Agassiz’s writings for an AP U.S. History class, her frustration grew. She began a campaign for the Agassiz neighborhood to change its name. The new name would unquestionably be Baldwin. “There was no other person I wanted to advocate for.”

She began reaching out to Cambridge city councilors, talking to local activists, and attending community meetings. The initiative did not pass the first time, but she regrouped and spent the next three years working closely with the support of Cambridge City Councilors Sumbul Siddiqui and E. Denise Simmons and Agassiz Baldwin Community Center Co-Executive Director Phoebe Sinclair. The effort channeled through the sometimes obscure and tedious processes of local government.

“I just knew at the bottom of my heart that people didn’t like the name. It wasn’t just me. I trusted that,” she said.

In August 2021 the Cambridge City Council voted 9-0 to rename the neighborhood to Baldwin. Counter celebrated the change as an undergraduate on the cusp of her sophomore year at Harvard College. “I think it’s important to recognize the people who have historically been pushed out of being honored, despite their incredible work, especially because of the color of their skin. If we can do that today, why not?

“There’s a lot more work to do,” she said. “We live in this country, and it has a lot of scary legacies. I would encourage people to just question everything they see on the streets and be open to relearning and unlearning.”