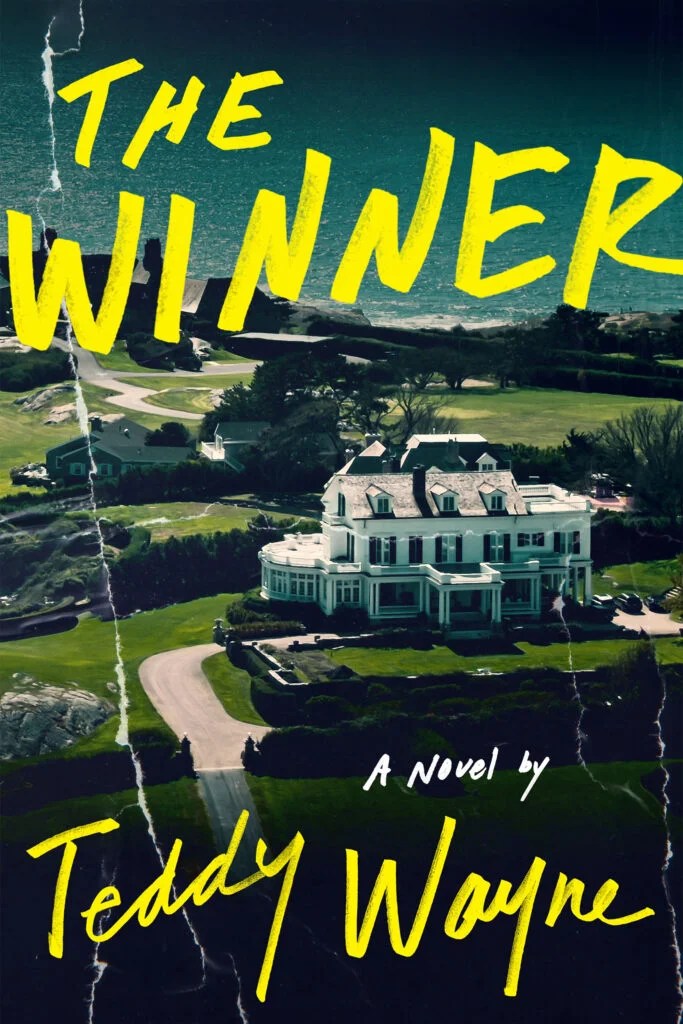

Photo by Tracy Pennoyer

American Dream turned deadly

He just needs to pass the bar now. But blue-collar Conor’s life spirals after a tangled affair at old-money seaside enclave in Teddy Wayne’s literary thriller

Excerpted from “The Winner” by Teddy Wayne ’01, published by Harper, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers.

John had told him the cabin also had an outdoor shower in the back, so Conor decided to try it out. He’d never taken a real shower outside before. Wind channeled through the wooden stall’s eye-level window, which showed the blue-green water in the distance. His mom’s windowless bathroom in Yonkers was cramped to begin with, and they’d been too afraid of Covid to have someone come in and repair the exhaust fan that had malfunctioned in April; every shower now produced a claustrophobic sauna.

He couldn’t believe his good fortune — not only to have a desperately needed job, but for it to include an open-air shower with an ocean view.

A few minutes before six, he tucked a button-down into his lone pair of khakis and headed over to the party. He felt himself growing nervous as he approached, uncertain if he was dressed appropriately. (Should he have packed his blazer? Where did you even buy pink shorts?) His work as a tennis pro had thrown him together with plenty of well-off older people in his life, and he knew how to act around them: be exceedingly polite, good humored, and deferential, like a waiter at a high-end restaurant. Cutters Neck, however, was the most rarefied stratum he’d encountered, and more to the point, he’d never lived among them on their home turf.

A few dozen guests milled about behind the party house by an infinity pool that appeared superfluous, surrounded as they were by near-infinite ocean. The crowd was composed predominantly of boomers who, like John, had sought refuge from the virus here, along with a clique of college-aged or high-school kids and several gaggles of frolicking children and their parents.

Conor immediately noticed that there wasn’t a mask in sight. Even if the recent George Floyd protests had suggested that outdoor gatherings might be safe, a crowded party was risky enough to make him consider turning around. If he contracted Covid, no one would take a lesson from him for two weeks, minimum.

But he also needed to rustle up more work. Not wanting to draw attention as either a hypochondriac or as someone who might have symptoms himself, he kept his mask pocketed and beelined for the hors d’oeuvres, as he hadn’t eaten anything substantial since breakfast. When the two people before him plucked deviled eggs from a tray with their bare hands, though, he pivoted away from the food and fixed a gin and tonic.

John found him and led him into the fray. The men, a couple of whom also wore pink shorts, with one in tomato-red pants, all gave their first and last names as they shook hands, so Conor adopted the custom. He met John’s friendly wife — who said she got her exercise in not by playing tennis but by cutting invasive plants on the neck — and the three people who had already signed up for lessons. To everyone else John introduced him as the exceptional tennis pro from Westchester (not Yonkers, Conor noted) whose slots were filling up rapidly. Most of them commented, discouragingly, that they didn’t play or hadn’t in years. Many residents bore a family resemblance to one another, save for one rumpled, wild-haired eccentric who spoke at length about the dangers of toxins in water.

Other than him, the Cutters residents were gregarious and welcoming, and Conor began to relax. Very rich people were still people. “Good God, you’re handsome!” gushed their hostess, the gray streaks in her hair betraying a recent disruption of regular salon appointments. “Are you sure you’re a tennis pro and not a movie star?” “My last acting role was in second grade,” he said with a self-conscious lowering of his head. The embarrassment was real, even if the abashed smile and deflective modesty were effectively habit by now. He knew, from experience, this was the only acceptable response, because to dismiss the compliment altogether was almost more egotistical than embracing it.

His effect on women was the one area of life where he’d never had to put in much effort. It was pure genetic luck, absolutely a perk, but, on occasion, it gave him a partial understanding of the drawbacks that he imagined beautiful women felt more often: being desired and objectified at once, ogled yet not seen at all. Some people — his professors, especially — assumed he was an idiot until he disproved them.

He certainly wasn’t complaining, but if he could have chosen a natural-born advantage, he would have taken money. So many things, from his mother’s health to his career prospects to the basic convenience of not having to haul his luggage across four states by bus, would have been much easier.

“Then how about politics?” the woman, whose name Conor didn’t catch, was saying. “You look like you could be the president. Doesn’t he look like a president, John?”

“He does have a certain Kennedy-esque air,” John said. “Before I give you my vote, you got any skeletons in your closet? Drive anyone off a bridge?”

“No one they’ve found yet,” Conor said, even more uncomfortable now under John’s scrutiny. “You have a beautiful pool, by the way,” he added, hoping to change the topic.

“Thank you,” she said. “You know, Suzanne Estabrook actually stayed at the same hotel with Teddy Kennedy on Martha’s Vineyard the weekend of Chappaquiddick?”

The conversation naturally swung around to the presidential election. “Tom Becker’s voting for him,” she confided.

“You’re kidding me — again?” John asked. “He hasn’t learned his lesson?”

“He wouldn’t admit it at first. Sally had to practically pry it out of him.”

“Don’t worry,” John told Conor. “There are only five or six Trump voters on the entire neck. We’d love to get rid of them, if you have any ideas.”

After some discussion of Covid (the hostess: “I hate to say it, but it’s a class thing more than anything else. I’d be absolutely shocked if anyone on Cutters dies from it. I don’t even think anyone here will get it”; John: “Oh, we’ll all get it. Eventually we’ll all get it. The only question is when”) and gossip about a postponed wedding on the neck and the couple’s extravagant registry (a Tiffany fork — a single fork, the hostess clarified, not a set — cost three hundred and sixty dollars), John left to say hello to someone. The hostess peeled off, telling Conor that she and her husband were going out of town on Monday for two weeks but that he was welcome to use the pool in their absence.

“Thank you,” he said. “Though I’m not much of a swimmer.”

The young girl he’d seen driving the golf cart skipped by in a floral dress and joined a group of similarly attired children. Amid the snowy tundra of white skin at the party was a single Black family, the popular-looking father and son in near-matching polo shirts.

The event had been a bust for drumming up business. He should slip out now, while John was occupied, but the cocktail he’d been nursing had only emphasized how empty his stomach was. He returned to the hors d’oeuvres when no one was around and, prudence chipped away by his gin and tonic, gobbled four of the creamy halved eggs in succession. Then he picked up the bottle of top-shelf gin to wash it down but, before tilting it into his glass, held it deliberatively with both hands. He had to make up for the day of exam prep lost to the bus ride, and one drink was his limit for retention of his books.

The college kids chatted in a circle by the pool. Though few of them looked old enough to drink legally, they all held tumblers or wineglasses with body language that suggested a lifelong familiarity with seaside cocktail parties. They laughed the carefree laughter of young people who don’t have to study for anything, who don’t have jobs they have to wake up for in the morning, who can drink as much as they want without consequence. Conor couldn’t imagine ever feeling the way they did. There had always been a morning tennis practice or a workplace to punch into, money to earn to help with rent, a looming test or paper or thick book. Although that was mostly all right by him. He felt best when he was working hard. Downtime made him restless. But his alienation from his peers wasn’t just from the gap in responsibilities. Nor was it the fact that he was always a little lost when they gossiped, in slang he was behind the curve on, about a new TV show or song or celebrity or something trending on the internet. It was how they spoke about themselves, what they freely divulged to anyone who would listen, flaunting frailty as a show of strength, taking pride in wounds and weaknesses that had once been shameful. Good for them, Conor supposed, but broadcasting one’s vulnerability to the world was unfathomable to him. In a tennis match, you never revealed an injury to your opponent if you could help it.

An unsettling image flashed into his head of himself barreling into the group, like a bowling ball into a cluster of blond wood pins, and knocking the rich kids into the pool.

As he was about to set down the gin in favor of sparkling water, a voice behind him, low but distinctly feminine, asked, “Are you going to pour that bottle or cradle it to sleep?”

The woman was tall, close to Conor’s height. Oversize sunglasses reflected the setting sun, and the wide brim of a straw hat shaded a bloodlessly pale face whose pointed features carved the air before her like the prow of a ship. Her medium-length hair was almost as yellow as that of the ubiquitous children. A network of blue veins peeked through the nearly translucent skin of her sinewy arms.

“Sorry,” he said. “Did you want — May I pour you some?”

She held out her quarter-full glass as if he were a caterer. “Don’t be shy,” she said, crooking her finger after he made a modest pour. “I’m not driving.”

He obliged and topped her off with a splash of tonic, then, when she nodded at the ice bucket, plunked in two cubes with a pair of tongs.

“So,” she said. “I don’t recognize you. Are you a bastard?” “Excuse me?” He was thrown off enough by the obscenity that he wasn’t sure if he’d misheard her.

“A bastard is someone’s illegitimate son. I’m asking if that’s the reason I don’t recognize you.”

Her odd question, delivered without the inflection of a joke, made him momentarily forget why he was there. “No, I . . . I’m the tennis . . . pro.” Technically, he was certified only as a recreational coach, not a pro, but his former boss had recommended he stretch the truth to get this job.

“The tennis . . . pro,” she repeated robotically. “Do you go by your vocation, or do you also have a name?”

“Conor. O’Toole.”

“Oh, yes. There was an email about lessons.” She cocked her chin up; behind her sunglasses she was probably squinting with suspicion. “You’re not trying to con us all, are you, Conor O’Toole? You’re not a con man impersonating a tennis pro for some nefarious purpose?”

The woman said this without a smile and took a drink, training her sunglasses on him the whole time. Women rarely made Conor self-conscious, but within a minute of talking to her he felt fidgety and diffident, as though a clutch of pedestrians were watching him parallel park.

“Just here to give lessons,” he said.

“Quite utilitarian. Well, then, how does one receive a lesson from the very serious Conor O’Toole?”

“All my info’s in the email John sent around.” When she didn’t respond, he added, “It’s a hundred and fifty dollars for an hour-long lesson.” (Conor had initially proposed a hundred dollars per lesson, the going rate at his old tennis club, but John had said he would attract more takers if he charged a hundred and fifty, as “no one here will think you’re worth it if you don’t cost enough.”)

“It’s gauche to talk money,” said the woman.

This line was spoken more cuttingly than the rest of her teasing. He’d always believed transparency was for the benefit of the customer, but at the moment it was apparent that he’d grossly overstepped one of this world’s unspoken lines of conduct, exposing himself as every bit the impostor she’d labeled him.

“I’m so—rry,” he said.

A few weeks into eighth grade, Conor had developed a stammer, seemingly overnight. It began innocuously, a brief pause inserted into words here and there. But within a couple of months it invariably appeared if he spoke more than a few sentences, the delay extending tortuously; his mind would know what the next sound was, yet his tongue and lungs refused to cooperate.

His mother assured him that it would eventually go away on its own, but he was terrified it wouldn’t. He’d heard that Joe Biden, then soon to become vice president, had overcome a childhood stutter by reciting Irish poetry for hours in front of the mirror. Conor decided to do the same, but with the medical journals his mother brought home from the gastroenterologist’s office where she worked. He figured if he could negotiate the arcane jargon, then he could handle everyday speech.

It was almost comic in hindsight, a thirteen-year-old boy studiously enunciating until bedtime upper endoscopy and management of anal fissures from back issues of Diseases of the Colon & Rectum, but it had worked. By the time he entered high school, he’d conquered it — almost completely. The key was to stop thinking about it as soon as it happened, because if you didn’t, if you kept worrying it was coming back at full strength, it had a chance of taking root.

The woman’s sunglasses remained locked on him, as if privately documenting the existence of a defect, a marker of some innate inferiority. His body’s thermostat spiked, his hairline prickling with sweat. “I’m available Tuesday at five o’clock.” It sounded like she was setting the time, not asking if he were free.

“Sure,” he said, keeping his syllables to a minimum.

“I’ll see you then, Conor O’Toole,” she said and walked away.

Only later, when he was brushing his teeth at home, did he realize he hadn’t gotten her name.

“Con man with some nefarious purpose,” he said to himself in the mirror. He would be making six hundred dollars off these people his first week. If he was a con man, then he was a low-rent one.

Copyright © 2024 by Chico and Chico Inc.