Economic prospects brighten for children of low-income Black Americans, study finds

Opportunity Insights also finds gap widening between whites at top, bottom

Illustration by Roy Scott/Ikon Images

Economic prospects have improved in recent years for Black Americans born poor, according to new research from Opportunity Insights. At the same time, earnings have fallen for white Americans from low-income families.

The analysis, drawn from 40 years of tax and Census records, finds a dramatic narrowing of the economic divide between the poorest Black and white Americans. But it also reveals a widening gap between low- and high-income white people, driven by shifts in the geography of employment.

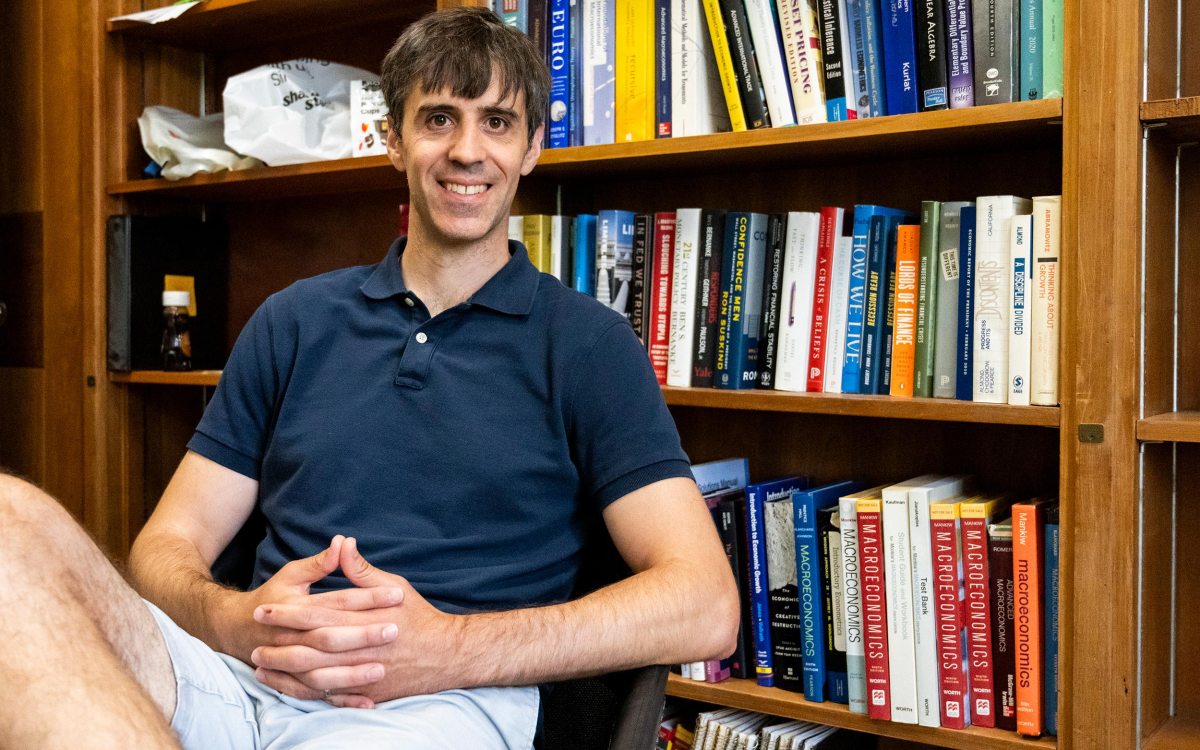

“This is the first big data study to look at recent changes in economic opportunity within the same place over time,” said study co-author Benny Goldman, M.A. ’21, Ph.D. ’24, a research affiliate with Opportunity Insights. “And what we see are shrinking race gaps and growing class gaps.”

The research, published last week, follows what Goldman called “a long history of folks studying intergenerational mobility.” That includes Opportunity Insights co-founder and director Raj Chetty, the William A. Ackman Professor of Public Economics and one of the study’s five co-authors. For more than a decade, Chetty has built an influential body of work demonstrating how access to the American Dream varies by region, race, and history.

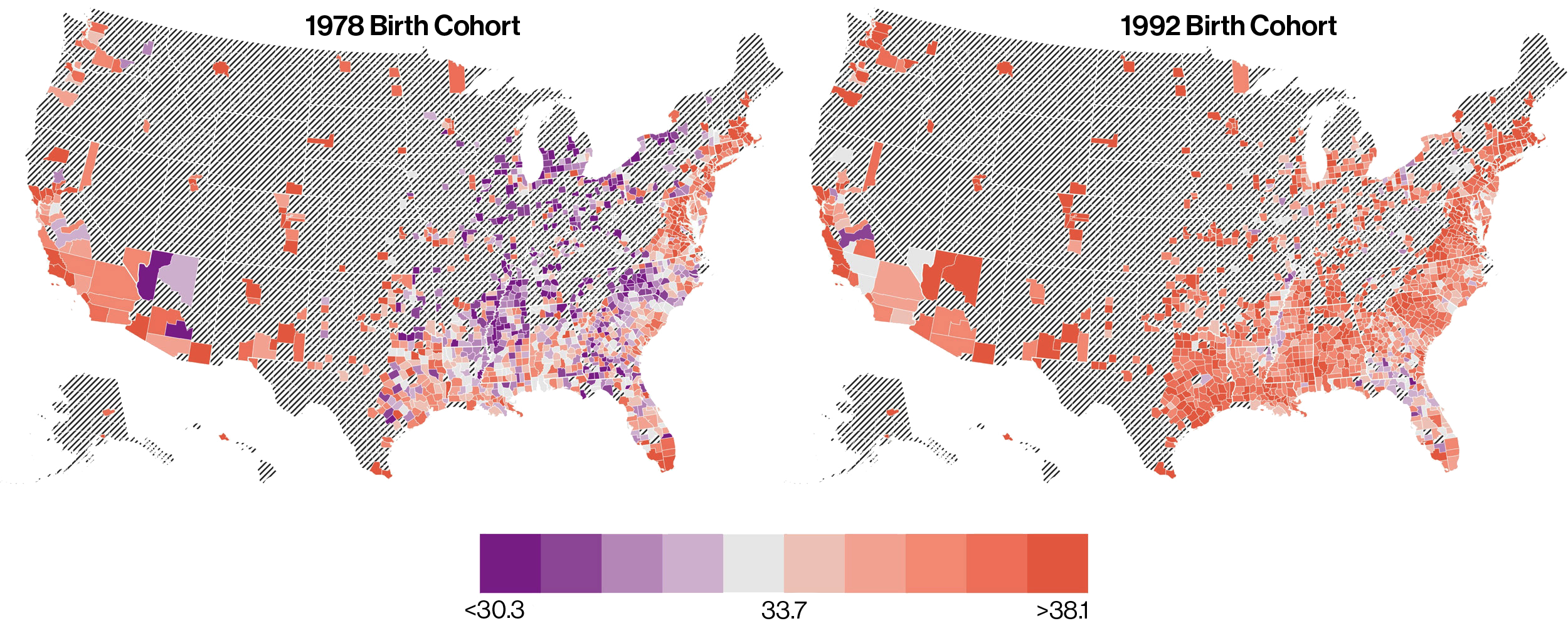

Changes in economic mobility of Black Americans

U.S. heat maps compare mean household income percentile at age 27 of Black Americans born in 1978 (left) vs. 1992.

“Changing Opportunity: Sociological Mechanisms Underlying Growing Class Gaps and Shrinking Race Gaps in Economic Mobility”

Social scientists have found the patterns he uncovered to be persistent. For example, a Swedish demographer compared findings from a 2014 study co-authored by Chetty on upward mobility across generations in the U.S. to the prevalence of slavery from the 1860 census. Counties with high rates of bondage at the outbreak of the Civil War showed less mobility for residents born more than 100 years later.

With the new study, Chetty et al. set out to investigate whether these dynamics are changing. Anonymized records provided by the federal government were used to compare earnings at age 27 with socioeconomic factors from childhood. The sample included 57 million Americans born in 1978 or 1992.

Across the country, the sample’s Black millennials fared better than its Black Gen Xers. Individuals born in 1978 to low-income families (with earnings in the 25th percentile or lower) averaged $19,420 per year in early adulthood compared to an inflation-adjusted $21,030 for poorer members of the 1992 cohort. Outcomes also improved slightly for children born to high-income Black families, though researchers noted “noisier,” or less reliable, estimates for this population due to a small sample size.

“What we see are shrinking race gaps and growing class gaps.”

Outcomes showed wide variation by region, with Black Americans making the biggest strides in the Southeast and Midwest — areas traditionally associated with high rates of Black poverty.

“Take where I grew up in Kalamazoo, Michigan,” offered co-author Will Dobbie, a professor of public policy at Harvard Kennedy School and faculty research fellow at the National Bureau of Economic Research. “Poor Black kids born there in 1992 were earning $4,700 more at age 27 than poor Black kids born there in 1978, an incredible improvement in just a few years.”

Meanwhile, white Gen Xers from poorer families averaged $27,680 per year versus $26,150 for millennial peers. The gap between the poorest and richest white people ballooned by 28 percent over the same period, as those born at the top watched their fortunes climb.

Results were particularly stark in a few regions of the country known for prosperity. “Outcomes for low-income white children born in the ’90s from parts of Massachusetts, Connecticut, rural New York, and California started to look like Appalachia, the Southeast, and the industrial Midwest did for low-income white children born in the late ’70s,” noted Goldman, now a newly installed assistant professor of economics and public policy at Cornell University.

“This work reinforces the importance of childhood communities for outcomes in adulthood, consistent with our prior findings,” Chetty wrote in an email. “But it shows that it is possible for these communities to change rapidly — within a decade — in a way that has significant causal effects on children’s long-term outcomes.”

$21,030 Inflation-adjusted average income for Black millennials at age 27 (vs. $19,420 for Black Gen Xers at same age)

To be sure, vast racial disparities persisted. For Gen Xers who grew up poor, the racial earnings gap between Black and white Americans was $12,994. For millennials, it fell 27 percent to $9,521. In a research summary, modest changes in economic mobility were noted for Hispanic, Asian, and Native American children.

But Black Americans in the younger set had a far better shot at moving out of poverty. Those born in 1978 to families in the bottom income quintile were 14.7 percent more likely to remain in poverty than similarly situated whites. For those born in 1992, the gap fell to 4.1 percent.

As an additional aspect of their analysis, the researchers check their findings against historic rates of parental employment at the neighborhood level. This approach was inspired by the work of Harvard sociologist William Julius Wilson, author of “When Work Disappears: The World of the New Urban Poor” (1996). “It was used as a broad way to measure the health of any given community where kids grew up,” Goldman explained.

The researchers saw that neighborhood employment tracked neatly with emerging race and class differences. “We found a sharp decline in employment rates among lower-income white parents relative to low-income Black families and higher-income white families,” Goldman said.

Declining earnings were hardly the only negative associated with growing up amid low parental employment. In a testament to the power of social connections, places with fewer working parents also saw rising mortality and falling rates of marriage.

Yet this wasn’t a case of opportunity moving from one group to another, since neighborhoods with higher rates of adult employment saw better outcomes for people of all races. “In areas where Black kids did best, low-income white kids and their parents also did better,” Goldman said.

What’s more, the researchers found that moving to areas with strong parental employment was associated with higher earnings in early adulthood. According to Goldman, this was especially true for those who landed in the new neighborhood before the age of 10. “Growing class gaps and shrinking race gaps did not result from unequal access to a booming economy,” he said. “Instead, what matters is how many years of childhood were spent in a thriving environment.”

Get the best of the Gazette delivered to your inbox

By subscribing to this newsletter you’re agreeing to our privacy policy